This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Patrice Dutil, April 5, 2022

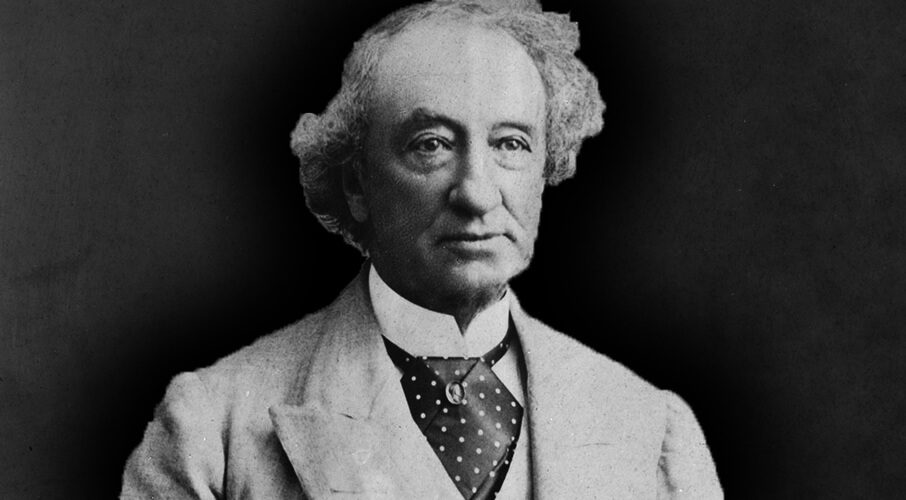

The vandalism carried out in the summer of 2021 against statues of Sir John A. Macdonald, Queen Victoria and Egerton Ryerson was supported by only a small fringe of Canadians. And a new Leger-Postmedia poll makes the case that Macdonald’s reputation has only improved with every attack — every time his name has been removed from a building and every time a monument to him has been taken down.

Considering the onslaught of hate against Canada’s first prime minister, this is remarkable. If polls can be compared, the Angus-Reid survey carried out in the summer of 2018 showed that 55 per cent of Canadians had a favourable view of Macdonald and were opposed to the removal of statues in his honour. In the summer of 2020, when Macdonald monuments were removed or destroyed in Charlottetown and Montreal, a Leger poll for the Association for Canadian Studies again showed that more than half of respondents were opposed to their removal (71 per cent were especially against any violent removal).

The new poll shows that Macdonald is one of the most recognized people in Canadian history. He beats out Métis hero Louis Riel, suffragette politician Agnes MacPhail and the father of Canadian medicare, Tommy Douglas. The survey also shows that 67 per cent of people who know Macdonald have a favourable impression of him, including 25 per cent who had a “very favourable” impression. Among those who claim to know Macdonald, ethnic origin makes practically no difference (67 per cent among Caucasians and 65 per cent among BIPOC respondents).

Other results are less encouraging. Fifty-three per cent of Quebec responders could not identify Macdonald as Canada’s first prime minister. This is hardly surprising as Canadian history has been practically absent from that province’s school curriculum for three generations. The revelation that 36 per cent of respondents in the Atlantic region had no idea who he was is perhaps more distressing, until one remembers that getting a credit in Canadian history is not required to graduate from high school in those provinces.

The real difference is age. The older you are, the more likely you are to know Macdonald. Seventy per cent of respondents aged 55 + said they were aware of Macdonald, and 72 per cent of them had a favourable impression of Canada’s first prime minister. In contrast, only 58 per cent among 18- to 34-year-olds were aware of Macdonald, but even among this group 61 per cent of them had a favourable impression. Twenty per cent of young adults had no idea who he was; neither did almost a quarter of respondents of all ages who identified themselves as BIPOC.

There is a refreshing openness to the historical record revealed in this latest survey. A plurality (44 per cent) of respondents agreed that “the whole story” of individuals like Macdonald had to be told. Canadians say they can take it — the good and the bad — but that arguments dismissing the positive role played by Macdonald and his generation win very little favour. Another 30 per cent felt it was “wrong to attempt to rewrite or ignore history in an effort to downplay the importance” of people like Macdonald “because their actions at the time do not look good by today’s standards.” Only one in 10 said that they were “embarrassed” by people like Macdonald. Those views were fairly consistent across the country, with respondents from British Columbia and Alberta being especially insistent on “telling the whole story.”

Most respondents (52 per cent) did not want to see Macdonald’s role to be seen exclusively through the lens of Indian residential schools. The support for Macdonald in this respect was stronger in Ontario and Alberta and weakest in Quebec and Atlantic Canada, but still commanded the majority view in those provinces. Interestingly, respondents living in Manitoba/Saskatchewan were especially hostile to the idea that Macdonald’s “negative contribution” to history be emphasized. Most respondents were also opposed to the idea that Canadians should “embrace the future and forget the past.”

Here is where I worry a little. According to the Angus-Reid poll taken four years ago, 70 per cent of Canadians “agreed” that the name and image of Canada’s first prime minister should remain in public view. The recent Leger-Postmedia poll showed that only 60 per cent of respondents agreed that Macdonald “needed” to be celebrated as an important figure in Canada. The questions were slightly different and can be compared only with skepticism, but the trend is not positive. More troubling is the revelation that many younger adults (36 per cent) agreed that Macdonald’s role should be downplayed and that “a greater focus be placed on his negative contribution” to Canada’s history.

The respondents to the Leger-Postmedia survey were aware that the past is not the present. Though 44 per cent of respondents said they were ready to “forgive the actions of certain historical figures and accept the good things they did in the development of Canada along with the bad,” more of them (46 per cent) said they didn’t know. Women and young adults were much less likely to agree with this statement, though 53 per cent of women signalled that it would depend on a case-by-case basis.

This avalanche of numbers shows one thing: Canadians are still attached to their roots and hunger for more knowledge about their history. They want more Canadian history taught in schools and they want to see it discussed in the media. They will reward public figures who are comfortable in talking about the past: people willing to acknowledge and even repair past injustices but who at the same time can speak of past generations without shame. They will punish those who know nothing about Canada’s past or who glibly talk it down.

Patrice Dutil is Professor of Politics and Public Administration at Ryerson University and a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. His Canadian history podcast is “Witness to Yesterday.”