This article originally appeared in the Regina Leader-Post.

By Danette Starblanket and Ken Coates, March 21, 2022

Canadians are trying hard to make sense of the “freedom convoy” that disrupted the country.

Even as the protests continued, transforming the nation’s political culture in the process, the public struggled to connect the convoy members frustrations with the COVID-19 pandemic and increased anger at the federal government with a profoundly discouraging political environment. In this sense, the convoy became the embodiment of Canadian angst, circa 2022.

But even as it continues to unfold, the convoy has many major flaws. The disruptions in Ottawa and at the Ambassador Bridge between Windsor and Detroit infuriated potential supporters and forced governments to respond.

The convoy’s fundraising efforts attracted scorn, largely because they copied environmentalists’ strategy of collecting financial, moral and media support from outside the country. Unclear convoy leadership has made it difficult for government, the media, and the public to get a concrete, sensible and meaningful message from the protesters and to understand the real demands and frustrations that underlie the movement.

But Canada has been down this path before, with different strategies used and with much better results.

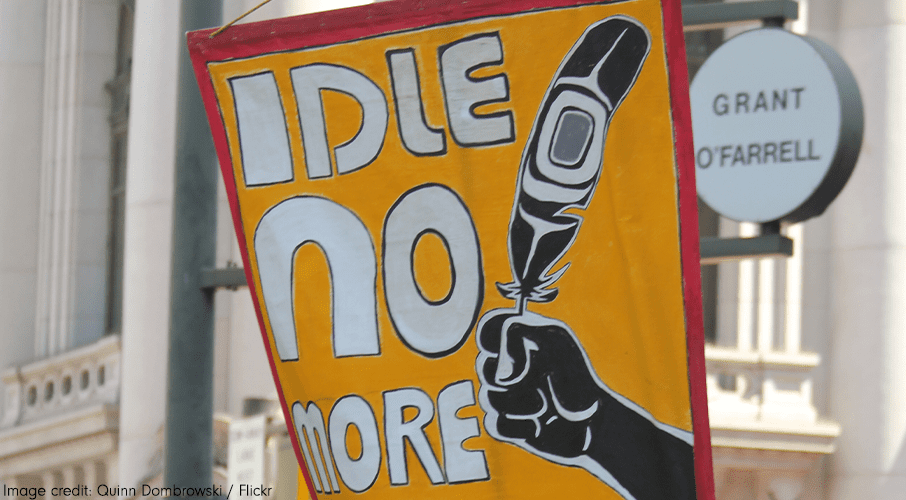

In 2012-13, Indigenous peoples across Canada, joined by non-Indigenous supporters domestically and internationally, launched a protest movement that can in some ways be compared, yet in many ways was so starkly different.

Organized in response to the omnibus bills (C-38 and C-45) of the Stephen Harper government, Idle No More transformed the model of Canadian protest movements. Using Facebook and other social media platforms to mobilize supporters, the loose coalition started by four remarkable women from Saskatchewan launched spontaneous rallies, flash mob round dances, teach-ins, demonstrations and other events across the country, which also moved across the globe.

While some governments quivered in fear of potential violence and wide-scale civil disobedience by the Indigenous protestors in 2012-13 — does this sound familiar? — the national and local coordinators oversaw literally hundreds of peaceful events.

These ranged from small, road-wide demonstrations to large urban rallies, including ceremonial drum groups performing in such locations as the West Edmonton Mall and the Mall of America, and large gatherings with speeches on Parliament Hill, to name a few. There were several marches on Ottawa, including a remarkable hike from Northern Ontario and a longer journey from Saskatchewan, both actively supported by people along the route.

The Idle No More events shared several things in common: they were short, caused few, if any disruptions to the lives of Canadian citizens, and focused on cultural celebration and treaty and Aboriginal rights education, all mixed with demands for political action.

The Idle No More movement was more a platform and an encouragement to step forward than an orchestrated and focused political campaign. Yukoner First Nations addressed territorial concerns. Mi’kmaq focused on Maritime issues. On the prairies, where the movement was the strongest, the Indigenous rallies emphasized unresolved treaty rights and protection of the lands and the environment. Collectively, the movement demanded the greater recognition of Aboriginal and treaty rights.

Many of the Idle No More events attracted hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people. But early commentators who talked about and reported on the insurgency and resistance paid little attention to the children and families in attendance, the ceremonial contributions of the elders offering the prayers, and the presence of traditional drum groups and dancers which highlighted most of the protests.

The events were, without exception, peaceful, calm and celebratory. If there were disruptions, such as a blockage of a road or a railway, with few exceptions they were done with consideration and lasted mere hours, if not minutes (there was a prolonged rail blockage that Indigenous leaders convinced the activists to remove).

Idle No More challenged people to listen and to acknowledge Indigenous rights and cultures; again, with very few exceptions, it did not interfere with, obstruct or threaten community life or other people’s health. Police officers, often dispatched by nervous commanders and politicians who feared an uprising, occasionally joined in the walks or, more often, listened attentively to the speeches.

The political force of Idle No More was disturbed by a parallel event, the hunger strike by Chief Theresa Spence in Ottawa, which had all the elements that media and politicians expected: a single story, a key individual, a straightforward message and an accessible location.

The Indigenous people, like the truckers, wanted to speak to the governor general and wished to place their demands before the state; they were able to do so. However, Idle No More, it turned out, was too complicated, nuanced and unanticipated for most non-Indigenous Canadians to understand.

The movement did not have a single message, beyond the demand that Indigenous peoples be heard on the issues they were facing. Many viewed Idle No More, at best, as a temporary success and a long-term failure. This view is inaccurate. Governments learned to pay attention, even if they really did not wish to do so.

The Harper government became more reluctant to shift its policy and strategy, but the newly minted Liberal leader, Justin Trudeau, internalized the central message of the Idle No More movement even if he and his party did not fully understand the complexity of Indigenous needs and aspirations.

Much of Canada’s Indigenous affairs and policy after 2013 has been influenced by the spirit and the intent of Idle No More. Indigenous grassroots peoples have become more insistent, assertive, and confident. Since 2012-13, Indigenous governments have been forced to respond as much, if not more, than provincial, territorial and federal governments, for the Idle No More critique emphasized the shortcomings of Indian Act governments.

Importantly, non-Indigenous people are more receptive to Indigenous concerns, demands, needs and aspirations. Public government and civil servants, who were initially worried about potential insurrections, gained an appreciation for the complexities and interconnectedness of Indigenous challenges and needs.

Idle No More changed the national conversation in good, constructive, and long-lasting ways. It was, looking at it a decade later, overwhelmingly successful and positive, for both Indigenous peoples and the country as a whole.

In the long term — and this is a lesson that Canadians must learn from Idle No More as they consider the outcomes of the convoy and its aftermath — the Idle No More movement did not end when the systematic protests stopped. Idle No More urged Indigenous people to speak up, to defend their interests and to assert local priorities.

In two ways — as a successful national protest and as a turning point in Indigenous assertiveness — Idle No More changed the way Indigenous people participate in Canadian public and political life and altered the way governments approach Indigenous policy making.

The convoy failed to learn the most important lessons from Idle No More. The Indigenous movement demonstrated that a peaceful, minimally disruptive but passionate assertion of political demands can have transformative effects on the country.

It is difficult to imagine, as the governments of Ontario, Alberta, and Canada wrestle with the aftermath of incredibly disruptive protests, that the politicians will internalize the convoy’s demands and critiques, let alone learn from the massive rallies and wide-ranging protests that new approaches are required to mollify the thousands of Canadians who supported the convoy. They are listening, instead, to the now-loud voices of the citizens of Ottawa, those upset by the interruption of trade with the U.S. and the many more Canadians turned off of the protests by their organizational failures and over-reach.

It would be extremely unfortunate if Canadians did not understand that the passions, assertiveness, and determination of the protesters, in both movements, will not soon disappear from the Canadian political landscape. The country has adapted, admittedly more in rhetoric and promise than practical action, to the demands and assertiveness of Idle No More. Canadians have to start now to figure out how they intend to respond to, or at least contain, the emotions, priorities and demands of the convoy.

The core lesson of Idle No More is that when the diplomatic power of citizen protest is demonstrated and mobilized across the nation, the country pays attention. The primary lesson from the convoy is that protests that cross the line of reasonableness and impose real costs on fellow citizens generate a counter-reaction that limits the effectiveness of the movement and destroys the sympathy of those who might have otherwise supported their protests.

Idle No More provided a lesson that the convoy failed to learn: it is possible to transform Canada’s political culture through a diplomatic, peaceful, respectful and sustained assertion of rights and expectations.

In the aftermath of the convoy, we stand, sadly, on the verge of discovering how Canada responds to massively disruptive, ideologically based protests that overstep bounds of Canadian civility and Canadian law.

Ken Coates is a Distinguished Senior Fellow, Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a Canada Research Chair in the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. Danette Starblanket is completing her PhD on Idle No More. She is a faculty member at the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the. University of Regina.