Ryerson would have been horrified by the abuses and cruelties later perpetrated on Indigenous children by residential schools, write Patrice Dutil and Ron Stagg. A longer version of this article first appeared in the Dorchester Review.

Ryerson would have been horrified by the abuses and cruelties later perpetrated on Indigenous children by residential schools, write Patrice Dutil and Ron Stagg. A longer version of this article first appeared in the Dorchester Review.

By Patrice Dutil and Ron Stagg , June 4, 2021

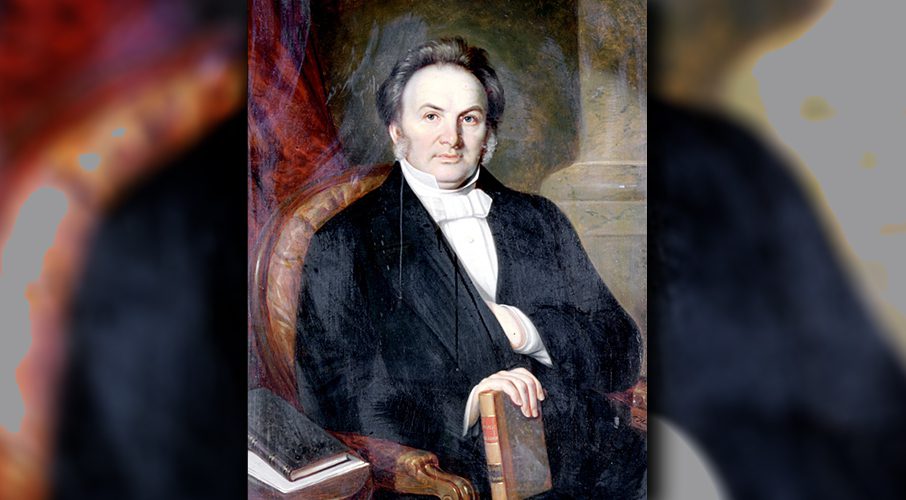

The revelation that there are 215 human remains buried on the grounds of the Indian Residential Schools in Kamloops, BC has prompted more vandalism of monuments erected to honour the men of the Confederation generation, and the statue of Egerton Ryerson that stands on Gould Street in Toronto has not been spared. It has also given a new wind to the demand that Ryerson’s statue be removed and that the name of the university dedicated to his memory be changed.

Egerton Ryerson (1803-1882), the Methodist minister who has long been celebrated as the founder of the Ontario public school system, stands accused of creating a residential school system designed to stamp out Indigenous culture. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission investigated the issue, but its final report made no such claim. It did not seem to matter: a small but nameless constituency still argues that Ryerson was the predecessor to federal politicians who launched new residential schools in 1883, and should therefore be erased from public memory.

Ryerson is being misjudged. He was not a racist and he did not discriminate against Indigenous people. It was the exact opposite! As a young man he was appointed to the Credit mission, home of the Mississaugas. He learned their language, worked in the fields with the people of the settlement and became a life-long friend of future chief Kahkewaquonaby (Sacred Feathers), known in English as Peter Jones.

In fact, it was in recognition of his services to the Mississauga, that Ryerson was adopted and given the name of a deceased chief, “Cheechock” or “Chechalk,” who had passed away recently.

After he left the Credit mission, Ryerson kept in touch with Peter Jones. In the 1830s he assisted the Mississaugas, whose land was confiscated by colonial authorities, by approaching Queen Victoria personally through back channels. He also advanced the careers of a number of talented Indigenous individuals. When Peter Jones was gravely ill at the end of his life, he stayed in the comfortable home of his old friend Ryerson in Toronto.

Ryerson was a friend of Indigenous people.

It is also wrong to blame Egerton Ryerson for creating residential schools. It was Peter Jones, working with another prominent Methodist, who argued that the government should fund schools to educate Indigenous men in the new techniques in agriculture, so that they might survive in a colony where land to hunt and fish freely was rapidly disappearing. By 1842, the authorities accepted the concept, as a way to put First Nations people on farms and to eliminate the expense of annual treaty payments, not as a way to assimilate them.

In 1846, government agents met with thirty chiefs, representing most of the First Nations in what is now southern Ontario. After some discussion, almost all the leaders agreed that such schools were necessary, and many even agreed to use part of their treaty payments to help support the schools. A year later, the government approached Ryerson, an acknowledged expert on education, and asked him to provide a curriculum for schools that would train Indigenous people for a settled life.

Ryerson was fully in agreement with the plan because he worried that Indigenous communities would be destroyed unless they changed their economic life. He delivered general suggestions for a curriculum—nothing else—that were typical of his day. It was patronizing, as it was based on Euro-Canadian models, but it had the support of most of the Indigenous leaders. Ryerson participated precisely because he saw education as the best instrument to protect First Nations from advancing settlement.

Two schools were established. They would be supervised by the government, and run by the Methodists, just like most of the on-reserve schools. They differed markedly from later residential schools, however. Teaching was done by teachers trained for the regular school system, not by the clergy, and children could speak their own language. Attendance was voluntary. Religion was a subject in the curriculum, not a tool of forced conversion and assimilation. As a devout Christian, Ryerson would have been horrified by the abuses and cruelties later perpetrated on Indigenous children by residential schools.

The schools were failures, mainly because of government refusal to adequately fund the project. But in this small aspect of his career Egerton Ryerson demonstrated his uniquely humane instincts of generosity and recognition of minorities. This was the same man who boldly championed schools for Catholics and for French-Canadians.

Torontonians today must recognize that Egerton Ryerson has been falsely accused and restore their pride in celebrating one of the best minds of their past.

Patrice Dutil is a professor at Ryerson University and Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Ron Stagg is a professor of History at Ryerson University.

This article initially appeared in the Dorchester Review and has been republished with permission. You can read the article on the Dorchester Review’s site here.