Beijing, Tokyo and Seoul all value more joint cooperation, or so they say. But given their historical grievances, and a host of new divergent interests brought on in the Trump era, all three have incentives to limit just how much they can work together, writes J. Berkshire Miller.

Beijing, Tokyo and Seoul all value more joint cooperation, or so they say. But given their historical grievances, and a host of new divergent interests brought on in the Trump era, all three have incentives to limit just how much they can work together, writes J. Berkshire Miller.

By J. Berkshire Miller, September 25, 2019

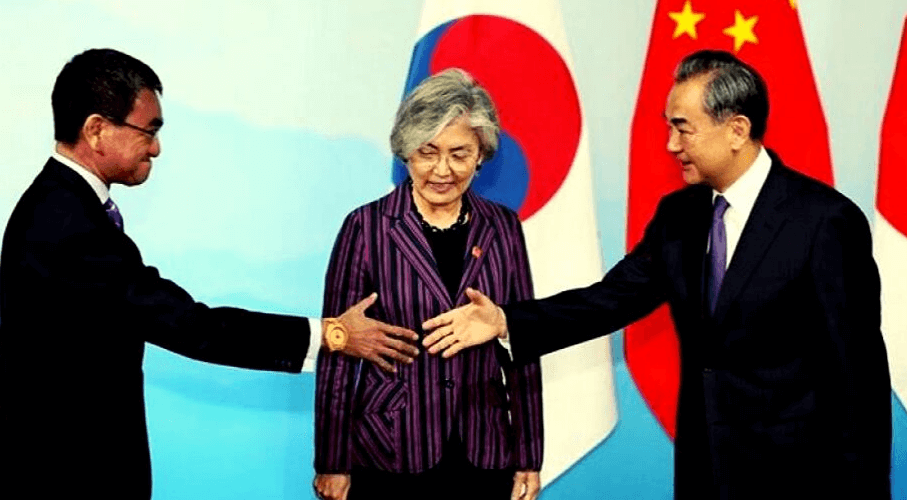

The foreign ministers of China, Japan and South Korea met in Beijing last month, where they agreed to seek closer economic ties and push for “free and fair trade” amid a climate of rising protectionism. A leader’s summit in China could follow later this year— an opportunity, perhaps, to resolve some festering troubles in a region mired in mistrust.

This diplomatic progress in collective ties comes at an inauspicious time. Attempts by Beijing, Tokyo and Seoul to work together have been undermined constantly over the past decade due to various rivalries in Northeast Asia. An inaugural trilateral leaders’ summit was held in 2008 in Beijing and was followed by consecutive meetings over the next four years, with the host nation rotating each year. Yet since 2012, the three leaders have only met twice—in 2015 and 2018—and meaningful progress on trade and other areas of cooperation have been scant.

Trilateral diplomacy initially ground to a halt as a result of crippled bilateral relations between Tokyo and Beijing over their territorial row in the East China Sea involving Japan’s Senkaku Islands, which China claims as the Diaoyu. Compounding tensions are historical issues from World War II and the perception, widely held in Seoul and Beijing, that conservative Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is bent on revising the traditional narrative of Japan’s culpability during the war.

But the stresses go beyond Japan and China. South Korea and China have also experienced their own strains, especially since 2016, when Seoul, under the administration of former President Park Geun-hye, proceeded with plans to deploy the advanced THAAD U.S. missile defense battery despite strenuous objections from Beijing. At the time, Seoul decided to go ahead with its decision as a response to North Korea’s sustained provocations. But the deployment of the American missile system enraged Beijing, which irrationally believes the weapon directly threatens its strategic interests. The fallout from THAAD, including China’s coercive economic measures aimed at curtailing tourism and trade from South Korea, continues to hang over their relations.

The revolving nature of these intra-regional tensions has gotten in the way of any sustainable cohesiveness between all three sides. Summits were out of the question in 2013 and 2014 due to tensions between China and Japan; in 2016 and 2017, strains between South Korea and China were to blame. While troubles still linger, Beijing has been showing more pragmatism in its approach to Japan and South Korea, largely as a result of its inability to manage tensions with both its two main neighbours and the Trump administration. But in recent months, there has been another flare-up, involving the already long-strained relationship between Japan and South Korea.

Ties between Japan and South Korea have arguably hit their lowest point since the end of World War II, over unresolved grievances stemming from the war era. Last month, their feud deepened with Seoul’s decision to back out of a key intelligence-sharing pact with Japan. The move has raised eyebrows in the U.S., which has mutual defense treaties with both countries. Washington should be rightly worried that the steady erosion of trust between its two most important partners in Northeast Asia has left no winners, outside of North Korea, China and Russia.

South Korea backed out of the intelligence-sharing deal over dissatisfaction with Japan’s decision last month to remove South Korea from its so-called whitelist of preferred trading partners. Earlier in August, Japan had imposed export controls on three key high-tech components, which Seoul called a punitive measure aimed at crippling a crucial part of the supply chain that large conglomerates, such as Samsung and SK Hynix, rely on to manufacture smartphones and other popular consumer devices. It sees Abe’s government as unfairly penalizing South Korea because of frustration over historical grievances.

Although this bed of intertwined rivalries has prevented more joint integration, and more leaders’ summits, trilateral meetings have still been held at the senior official and ministerial levels through what is known as the Trilateral Cooperation Secretariat. Established in 2011 to drive regional cooperation forward, it brings together ministers from a range of portfolios to discuss shared interests and potential collaboration on issues such as climate change, international finance, disaster relief and people-to-people exchanges. The secretariat’s political and security components have been marginalized by all the different bilateral strains over the past few years. But there has been coordination on health policy and trade, as well as discussions about promoting sustainable energy security in the region.

Given the ongoing trade war with the U.S., Beijing in particular has demonstrated an interest in boosting trilateral cooperation with its neighbors, even rebranding itself as a regional promoter of free trade and investment. However, despite their own concerns about Trump’s protectionist policies, Japan and South Korea hardly see China as the innocent victim of Trump’s trade war, considering Chinese policies on forced technology transfers, limiting market access and stealing intellectual property.

With a combined GDP of more than $21 trillion, China, Japan and South Korea continue to press forward on areas of economic integration, despite their mistrust. Already linked through interdependent economies, they are pursuing two major multilateral free trade deals: the China-Japan-Korea Free Trade Agreement and the larger, Beijing-backed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, known as RCEP, that would lower barriers to more comprehensive integration. Both agreements are undergoing intensive negotiations, after having completed 15 and 27 rounds, respectively. Yet both would lag behind the high standards of the salvaged Trans-Pacific Partnership, now known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, on key trade areas such as market access, the role of state-owned enterprises and e-commerce. And political mistrust, especially between Japan and South Korea in recent months, still stands in the way of both deals.

Finally, collective ties between China, Japan and South Korea are complicated by the larger strategic competition between the U.S. and China in Asia. The Trump administration labeled China a “strategic competitor” in its 2018 national defense and security strategies. Under Trump, Washington has also taken a much harder, and more realistic, view of its ability to induce Beijing to be more accepting of international laws and norms, whether regarding international trade or maritime security. U.S. alliances in the region, underpinned by Japan and South Korea, are in a precarious position as both countries seek to balance their engagement with China with Trump’s more transactional view of their ties with Washington.

Beijing, Tokyo and Seoul all value more joint cooperation, or so they say. But given their historical grievances, and a host of new divergent interests brought on in the Trump era, all three have incentives to limit just how much they can work together.

J. Berkshire Miller is deputy director and senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. He is also a senior fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, the Asian Forum Japan (AFJ) and a distinguished fellow at the Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada.