The principle of prosecutorial independence is designed to ensure that political factors do not impinge on the integrity of the rule of law, writes Brian Lee Crowley.

The principle of prosecutorial independence is designed to ensure that political factors do not impinge on the integrity of the rule of law, writes Brian Lee Crowley.

By Brian Lee Crowley, March 29, 2019

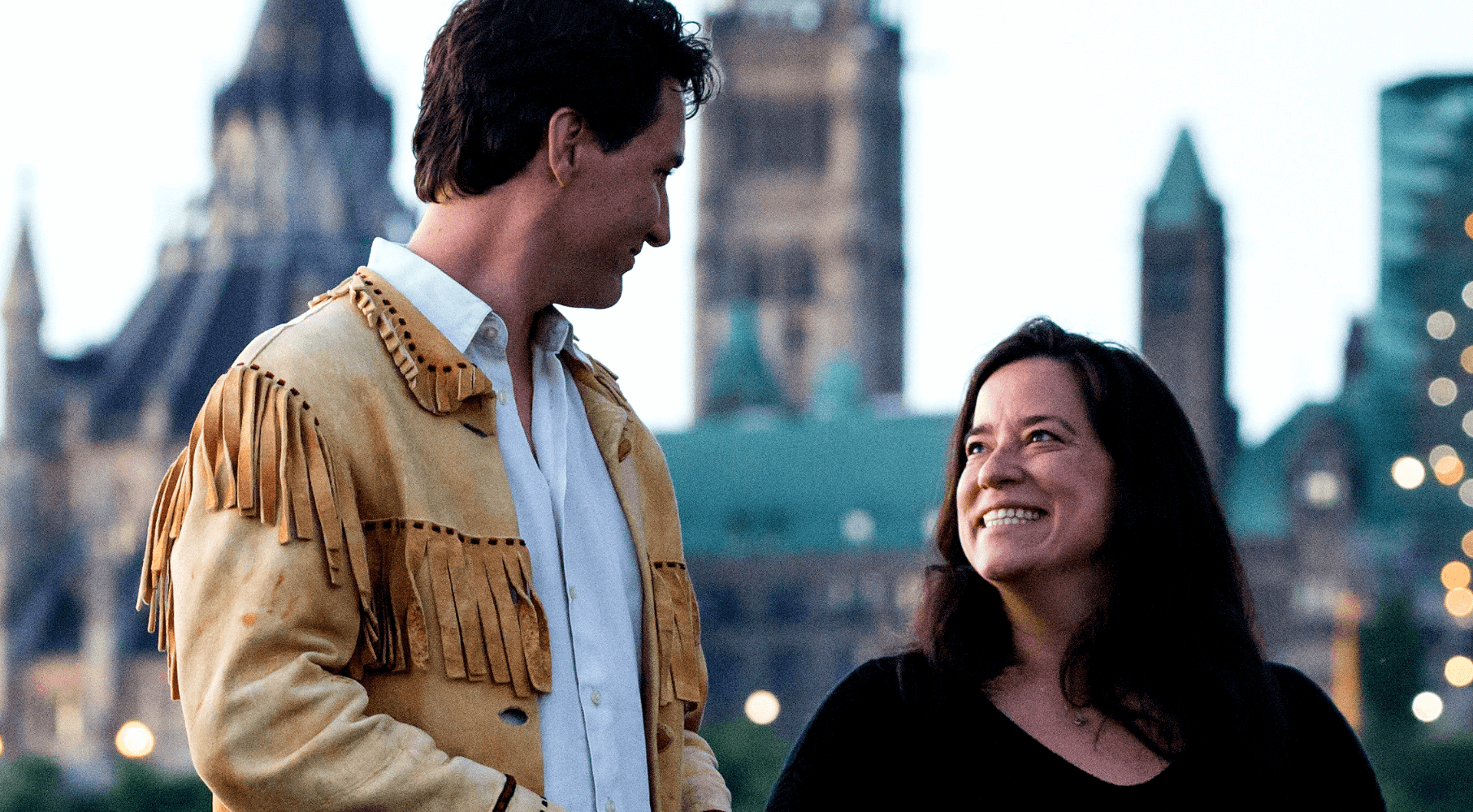

Prosecutorial independence goes to the heart of the “Lavscam” scandal currently embroiling the Liberal government in Ottawa. Everyone knows by now that this dispute has seen former Justice Minister and Attorney General Jody Wilson-Raybould and her colleague Jane Philpott resign from cabinet over allegations of improper political interference by the Prime Minister’s office and the Privy Council Office in a prosecutorial decision on an ongoing case against SNC-Lavalin.

Prosecutorial independence may well seem an obscure idea to many and the reasons why it looms so large in this dispute may be unclear. It seems to me worth a few minutes to unpack this vital concept and explain why it is at the heart of Lavscam.

Understanding the principle of prosecutorial independence requires us to think for a moment about what it means to be a society under the rule of law. To do so, it is perhaps easiest to look to places where the rule of law doesn’t exist. Take China or Russia, for instance, where the machinery of the state is under the unfettered control of political authorities, and can be used by those authorities to punish their enemies and reward their friends. People who incur the displeasure of political authorities can be arbitrarily imprisoned, prosecuted on trumped up charges and even assassinated. Their property can be seized. Their families may even be terrorised by the police.

Under the rule of law, recognising the danger the state can pose to our life, our security and our peace of mind, we subject the power of the state to various kinds of controls. Those controls aim to ensure that when the state uses its coercive power against us it does so to enforce the law, and only the law, as adopted by democratic processes.

As a shield against mistakes, and to keep cabinet ministers and others with political power from thinking the state exists for them to use at their pleasure, we have three separate decision-making bodies that determine if there is a case the law has been broken and then to decide if that case is proven. Those bodies are: the police, the prosecution and the judiciary. It is a fundamental principle of the rule of law that each of these agencies must be left free of political interference in their work.

The better known of these three are the police and the courts. We do not live in a society where cabinet ministers can call the head of the RCMP and say, “John Doe is a pain in the neck. Let’s teach him a lesson. Arrest him and throw away the key for a few months.” The RCMP, and other police forces in Canada, must be given the freedom to investigate crimes independently of political influence and subject to the legal limits on the police power.

It is the same with judges. Once a matter is before the courts, not only would it be scandalous for a politician to phone the judge and try to influence his or her decision, but public authorities are very careful not even to comment on matters before a judge, lest that be seen as an attempt to signal to the judge what a desirable outcome would be from a political point of view. When a citizen’s property, rights and liberties are in jeopardy, nothing less than this rigorous shielding of judicial independence is acceptable. Importantly, the judge cannot indulge his or her own preferences either. They are limited in what they can do by the law applicable to the alleged offence they are judging. A judge who oversteps these bounds will very likely be corrected on appeal. The whole system is designed to keep the focus on the law and only the law.

An independent prosecutorial service is just as important as the other two in safeguarding our liberties. Prosecutors examine the evidence in a case as put forward by the police and determine, without political interference, whether a prosecution is justified before a court and, if so, what the charges will be.

As was the case with the police and the courts, prosecutors are expected to be guided by the law, not the political preferences of governments. No politician is allowed to press for a prosecution in an individual case, or indeed for a prosecution to be dropped when powerful and influential people come under the scrutiny of the justice system. This is precisely what it means to be under the rule of law. Public authorities may not act arbitrarily or in pursuit of any objective but applying the law without fear or favour.

This is the nub of the dispute between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and former Attorney General Jody Wilson-Raybould.

SNC-Lavalin was the subject of a police investigation that found sufficient evidence to justify criminal charges of corrupt behaviour. The Director of Public Prosecutions had a choice either to bring the criminal charges before a judge or to negotiate a so-called Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) with the company. Under a DPA the company would admit wrong-doing and pay restitution but would escape the possibility (and consequences) of a criminal prosecution. DPAs are not available to all offenders, however; there are eligibility conditions that must be fulfilled.

The Director of Public Prosecutions determined that, under the law, a criminal prosecution was the correct route to follow (presumably in part because she felt the company did not meet the legal conditions for a DPA) and she notified the company of this decision. As the Attorney General, Minister Wilson-Raybould reviewed that decision and satisfied herself that it was correct under the law and that she would not issue an order, which she had the power to do, to pursue a DPA instead. The company, dissatisfied, launched a court case to try and get a judge to force the prosecution to pursue a DPA.

We had, therefore, an independent prosecutorial decision to forgo a DPA and pursue criminal charges and we had a case before the courts on these very issues; in other words, two reasons for politicians to give this matter a wide berth under the rule of law.

It was in this context that Jody Wilson-Raybould says she was subject to improper political pressure from a variety of sources around the prime minister, including Justin Trudeau himself, to change the independent prosecutorial decision. Trudeau and his advisors say they were only giving “context,” which they are entitled to do. But as Wilson-Raybould testified before the Commons Justice Committee, these interventions went far beyond “context” and included both urging that improper political factors be considered (such as alleged job losses at SNC and the impact of an adverse court decision on the government’s re-election prospects) and alleged veiled threats that her job as minister was at stake if she didn’t play ball.

While we are discussing the issues raised by Lavscam, it is worth noting that this dispute highlights certain weaknesses in Canada’s regime of prosecutorial independence that can and should be corrected. For instance, it turns out that the DPA legislation was poorly drafted, containing as it does potentially conflicting criteria for DPA eligibility. Lavscam also raises the question of why the Attorney General even has the right to interfere in the prosecutor’s decision in the first place, although it is possible to imagine compelling public policy considerations that might justify this review power. But for this review power to be made safe and ensure it is only used in extremis and for publicly known and defensible reasons, the Attorney General should be required to notify formally in writing the Prime Minister’s Office and the Privy Council Office once a determination has been made as to whether the prosecution or the DPA route has been chosen. Once the government is notified of the Attorney General’s determination, further efforts at “persuasion” on already considered facts should be regarded as improper and not allowed.

Back to the scandal itself. Clearly the entire story has not been told, not least because the prime minister will not give Jody Wilson-Raybould a waiver from her oath of cabinet secrecy to do so. Until such time as we possess more facts, it would certainly appear that there is a case for the prime minister to answer about whether he acted improperly and in violation of the principle of prosecutorial independence. Moreover, if threats (veiled or not) were made to the Attorney General regarding loss of her position based on her use of her legal discretion in a specific individual case like SNC Lavalin, it would certainly appear that this would qualify as a serious breach of the high ethical standards protection of the rule of law requires. If the prime minister, or his advisors, did so, their claim that they were only acting to defend Canadian jobs is actually no defence at all and entirely misses the point.

Even if you think that jobs were at stake in the SNC-Lavalin affair (and there are strong reasons to be sceptical) the principle of independence at stake is intended precisely to prevent politicians from attempting to override the rule of law because it conflicts with their political interests. In such a contest the integrity of the rule of law must carry the day.

Brian Lee Crowley is managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.