We are at an inflection point in the global system where the forces of illiberalism and repression are ascendant, especially in China, writes Richard Shimooka.

We are at an inflection point in the global system where the forces of illiberalism and repression are ascendant, especially in China, writes Richard Shimooka.

By Richard Shimooka, August 27, 2018

In the late hours of August 20th 1968, Soviet and Warsaw pact columns launched a massive invasion into Czechoslovakia, crushing a nascent liberalization movement that had been unfolding over the previous eight months. In the face of a Soviet and Warsaw Pact force that numbered over 250,000 there was little that could be done. After a week of violent protests and civil disobedience, the movement collapsed.

For the Czechoslovak people, the Prague Spring represented the embodiment of a long-suppressed nationalism and desire for self-determination that had emerged among a younger generation. They fed off the great hope that had accompanied the initial creation of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918 until it was dismembered by Nazi Germany 20 years later.

For citizens, the invasion and subsequent events was a gutting blow. Popular reforms were reversed and replaced by harsh repressive measures. Lists of dissidents were drawn up, draconian surveillance practices were imposed and large-scale detentions occurred. No act reflected the despondency better than the self-immolation of Jan Palach and Jan Zajic in early 1969. Their sacrifice helped to steal the nation for the long struggle. Protests continued, and activists worked to undermine the government, the most famous example being the Charter 77 movement. While unsuccessful at overthrowing the government alone, they were an important part of a much greater effort that culminated in Communism’s collapse in 1989.

The Prague Spring anniversary is timely as it comes during an inflection point in the global system. Indeed, the forces of illiberalism and repression seem all the more powerful today than at any time since the collapse of the Soviet Union. One particular area of concern is the power that emerging technology has provided government – from social media to advanced data collection systems.

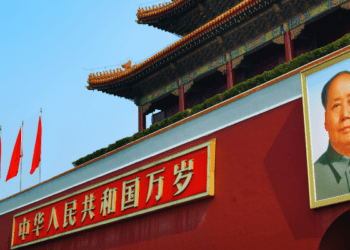

Some of the social credits system’s tools are already being employed in China’s Xinjiang region.

A frightening example is China’s social credit system, a vast data collection program that will rate people according to their adherence to norms set down by the Communist Party. Those who are rated highly – by being supportive of the state, not having friends or acquaintances with low scores, or who live in accordance to state-approved policies – could gain benefits such as faster Internet service or greater ability to travel. But those who have low scores could be subject to roadblocks to their social mobility, and even forms of coercion or re-education.

China’s ambitious plan is based on what some have called algorithmic surveillance. It monitors every citizen by drawing in data from a wide variety of sources; surveillance cameras employing facial recognition software, internet browsing history, financial data, among many others. It’s a system the great Bohemian author Franz Kafka could only dream up, providing the government unbelievable levels of potential repressive control. It could enable security services to suppress discontent long before it becomes a supposed threat.

Some of the social credits system’s tools are already being employed in China’s Xinjiang region, where nearly a million minority Muslim Uighurs have reportedly been sent to re-education camps, according to testimony given to a UN Committee. China has relied on highly intrusive measures, going as far as DNA profiling its residents. While it’s unlikely that all of these severe measures will be adopted in the rest of China, the region almost certainly serves as a test bed for some before implementation. And given the nature of technological progress, it is only a matter of time these tools proliferate to other illiberal states such as Russia.

The social credit system, and the advanced technologies that underpin it, are the new face of repression. The Prague Spring offers hope to overturn it, but it requires countries like Canada to adopt and enforce innovative policies with appropriate resources; they will not be solved through a single tweet. As Samantha Hoffman, from the International Institute for Strategic Studies, suggests, these policies should include preventing the export of enabling technologies, strengthening democratic resilience to counter foreign interference, placing it squarely as a human rights issue under the purview of Magnitsky legislation, and protecting overseas Chinese communities from the social credit system’s reach.

These concrete steps can have an impact, but they require years of credible government action to be successful. Canada is well placed to play a leading role in this emerging human rights area, combining its desire to spread liberal values with its high levels of technological development. Failure to respond will only lead to more misery, perhaps on a scale greater than that felt in Prague 50 years ago this week.

Richard Shimooka is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Centre for Advancing Canada’s Interests Abroad.