This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Dave Snow, December 2, 2024

Suddenly, everyone is talking about prorogation. As questions swirl around Justin Trudeau’s leadership, many have predicted the prime minister might prorogue Parliament to buy himself some time (if he stays), or buy some time for his successor (if he goes). This renewed interest in prorogation provides an opportunity to understand why it has become so controversial.

As my analysis shows, prorogations have garnered considerable media attention since 2008, but prime ministers tend to weather the political storm. In particular, both Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau successfully framed prorogation as an opportunity to reset the government’s agenda and focus on the economy. Given the current parliamentary and economic uncertainty, we should not be surprised if Trudeau uses this strategy again in early 2025.

Prorogations

After an election is held, a new Parliament is convened and begins its first “session.” Prorogation terminates the session, putting an end to parliamentary business. When prorogation occurs, government bills die on the order paper (with rare exceptions); parliamentary committees “cease to exist” and are reconstituted in the next session; and a throne speech eventually marks the beginning of a new session. While technically proclaimed by the Governor General, the decision to prorogue is made on the advice of the prime minister—advice that is, in practice, always taken.

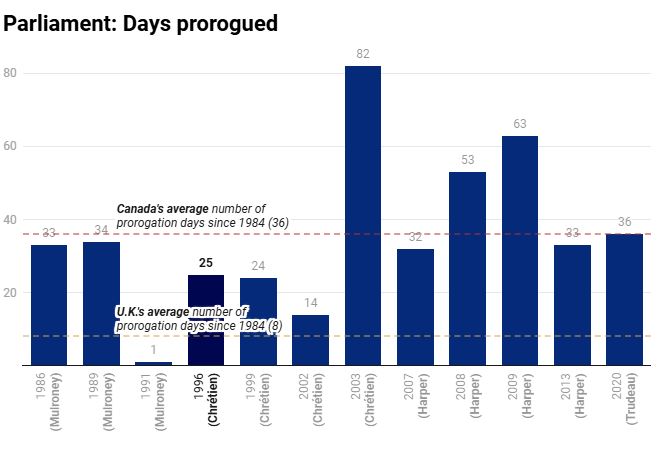

Since Brian Mulroney’s majority victory in the 1984 election, there have been a total of 12 prorogations, an average of one per Parliament. Stephen Harper and Jean Chrétien each prorogued Parliament four times over their three Parliaments in power, while Brian Mulroney prorogued three times across two Parliaments. By contrast, Justin Trudeau has only prorogued Parliament once, and neither Paul Martin nor Kim Campbell prorogued Parliament. Most prorogations have been routine, although Chrétien’s lengthy 2003 prorogation included time to allow for Martin to transition into the Prime Minister’s Office. More recently, prime ministers have been criticized for using prorogation to avoid scrutiny from parliamentary committees or a looming non-confidence vote.

As the graph below shows, since 1984, the average number of days per prorogation has been 36, though that number has trended upward, with an average of 50 days since 2003. This is much higher than in the U.K., where the average length of prorogation since 2003 has been only nine days (in general, the Brits move faster when it comes to parliamentary transitions).

Media attention towards prorogation has increased since 2008

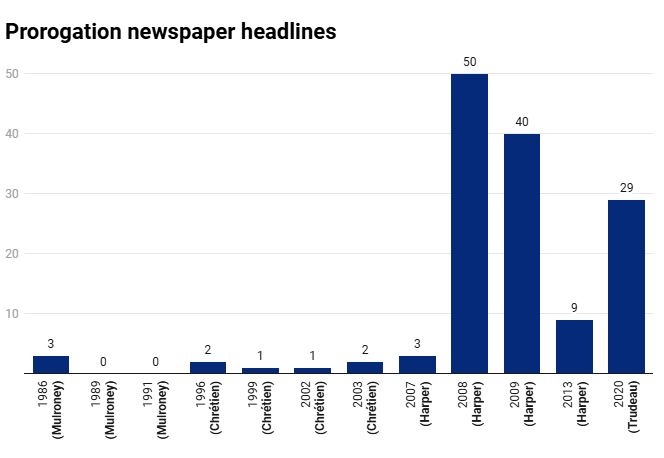

To see how prorogation has been discussed in the Canadian media, I used Canadian Newsstream to determine the number of unique English-language newspaper stories containing “prorogue” or “prorogation” in the headline. The graph chart below shows the number of such stories for a two-week period (one week before and after prorogation) from Brian Mulroney’s 1986 prorogation to Justin Trudeau’s 2020 prorogation.

The data confirm what Carleton University political scientist Philippe Lagassé has noted: that prorogation has been synonymous with controversy ever since the 2008 “coalition crisis” described below.

For example, while there was partisan criticism of Chrétien’s prorogation in 2003—with then Canadian Alliance leader Harper calling it a decision to “get out of town just one step ahead of the sheriff” to avoid fallout over an upcoming auditors’ general report—it received minimal media attention.

By contrast, the media has paid far more attention to prorogation since 2008, with 50 newspaper headlines mentioning the term in 2008, 40 in 2009, nine in 2013, and 29 in 2020.

How prime ministers justify prorogation

Given this increased media attention, I also analyzed how recent prime ministers have justified the practice. In all four prorogations since 2008, Prime Ministers Harper and Trudeau were forced to respond to criticisms that prorogation was designed to avoid a negative political outcome: a non-confidence vote (2008), committee revelations about Afghan detainees (2009), questions regarding the Senate expense scandal (2013), and committee hearings regarding the WE Charity scandal (2020).

It is worth briefly revisiting the political events that led to Harper’s 2008 prorogation, which began this trend of prorogations being viewed as controversial. Shortly after the 2008 election, the Harper government released a fiscal update that opposition parties felt responded insufficiently to the emerging global economic crisis (not coincidentally, it also promised to eliminate political party subsidies). The opposition parties agreed to replace the government with a Liberal-NDP coalition supported by the Bloc Québécois.

In order to avoid a looming non-confidence vote, Harper requested that the governor general prorogue Parliament, a gambit that ultimately paid off politically. By the time Parliament resumed for its new session nearly two months later, the Liberals had replaced leader Stéphane Dion with Michael Ignatieff, the coalition agreement had fallen apart, and the Liberals supported the subsequent federal budget.

Harper’s official statement after the prorogation justified the procedure by claiming Canadians wanted the government “to continue to work on the agenda that Canadians voted for,” namely to “strengthen the economy.” In his televised speech to the country the night before his prorogation request—which did not mention the word prorogation—Harper highlighted three issues: the supposed democratic illegitimacy of the coalition, the involvement of the Bloc Québécois in propping it up, and the government’s need to introduce economic measures to address the global economic crisis: “This is no time for backroom deals with the separatists; it is the time for Canada’s government to focus on the economy and specifically on measures for the upcoming budget.”

Of the four most recent prorogations, 2008 was the only time the prime minister’s justification effectively matched the opposition’s critique—in this case, that Harper was proroguing Parliament to hold onto power.

Subsequent prorogations have been less controversial but have remained politically salient. In 2009, Harper was criticized for proroguing Parliament to avoid committee hearings on Canada’s treatment of Afghan detainees. Harper also appointed five Senators after Parliament was prorogued, which gave the Conservatives a governing majority in the Senate for the first time in Harper’s tenure. In an interview with Peter Mansbridge, Harper rejected that prorogation had anything to do with Afghan detainees, saying “polls have been pretty clear… that that’s not on the top of the radar of most Canadians.” Instead, he described prorogation as a “routine constitutional matter,” noting that “there’s nothing particularly unusual about a session of Parliament being roughly a year in length” (from 1984-2009, the average session length had been 486 days, with two of 13 pre-Harper sessions lasting less than a year). Harper also said prorogation was an opportunity to “take some time to recalibrate the government’s agenda.”

After proroguing Parliament in 2013, Harper similarly brushed aside concerns about an ongoing Senate expenses scandal. He referred to prorogation at the mid-point of a majority government as a “completely normal” procedure used to set a new agenda: “We have been able to adopt virtually all of our legislation to this point in Parliament,” Harper said. “There’s a need to refresh legislation.”

Justin Trudeau’s 2015 Liberal election platform categorically stated “Stephen Harper has used prorogation to avoid difficult political circumstances. We will not.” While Trudeau did not prorogue Parliament during his 2015-2019 majority Parliament, he did prorogue Parliament in 2020 amidst difficult political circumstances.

Trudeau’s prorogation was criticized for halting committee hearings into the WE Charity Scandal, whereby the government was accused of giving special treatment to a charity with close ties to Trudeau, his family, and his finance minister.

Like Harper in 2009 and 2013, Trudeau deflected opposition criticism, characterizing the 2020 prorogation as an opportunity to refresh and respond to the changing circumstances posed by the COVID-19 pandemic: “It is obvious that the throne speech we gave eight months ago is no longer relevant for the reality that Canadians are living and that our government is facing,” Trudeau said. He pointed to the Liberals’ plan for “building a stronger economy that is more inclusive, that is greener, that is fairer for all Canadians.” Trudeau even made a direct contrast to Harper’s prorogation in 2008: “Stephen Harper and the Conservatives prorogued Parliament in order to shut it down and avoid a confidence vote. We are proroguing Parliament to bring it back on exactly the same week it was supposed to come back anyway and force a confidence vote.”

How the media are framing a possible prorogation today

Amidst uncertainty over Trudeau’s leadership and an increasingly dysfunctional Parliament, media interest in prorogation has returned this fall. To determine how the media has framed the possibility of a 2024 prorogation, I conducted a content analysis of stories that mentioned the possibility of Justin Trudeau proroguing Parliament across five national venues—the Globe and Mail, National Post, Toronto Star, CTV News, and the CBC—between September 1 and November 18, 2024.

In total, 28 articles mentioned the possibility of the Liberals proroguing Parliament: 10 from the Star, six from CTV News, six from the Post, five from the Globe, and one from the CBC.) The same Canadian Press wire story was published in both the Star and CTV. This meant that in total, 27 unique stories were published across these four venues, 16 of which were hard news and 11 of which were opinion pieces. Surprisingly, the pieces made little mention of prorogations of the past. Of the 27 stories, only one mentioned the Trudeau Liberals’ 2020 prorogation, two mentioned Harper’s 2009 prorogation, and one mentioned Harper’s 2008 prorogation.

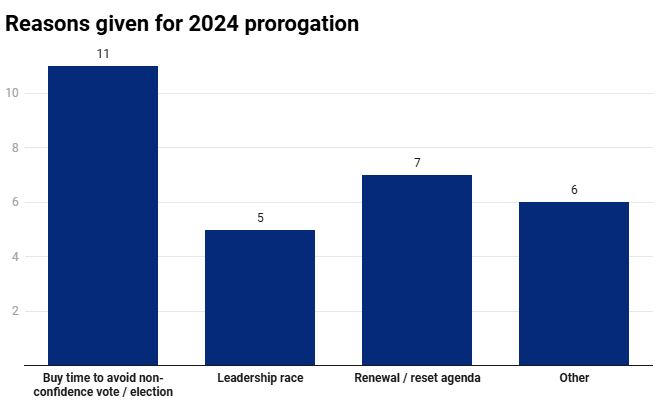

When questioned by media about prorogation, Liberal cabinet ministers Chrystia Freeland and Karina Gould both denied that the government intended to prorogue. As such, the government has not offered any prospective justifications for any potential prorogation. However, I categorized each story for how the media described potential justifications for prorogation. Of the 27 stories, 22 offered at least one reason the Trudeau Liberals might prorogue Parliament, with 29 justifications in total (as stories could include more than one justification).

The chart above shows the three major justifications offered for prorogation in 2024: buying time to avoid a non-confidence vote and subsequent election (11 times); allowing time for a leadership race if Trudeau resigns as leader (five); and providing an opportunity for the government to renew or reset Parliament with a new agenda (seven, with five of those stories using the term “reset”). The six other justifications related to focusing on byelections, addressing Canada-U.S. relations, responding to the U.S. election, disrupting ongoing committees, and stopping the current dysfunction in the House (twice).

Therefore there is a sense that Trudeau has many reasons to prorogue Parliament. Some of those reasons mirror those given by prime ministers for previous prorogations (a “reset” or holding onto power). But this is the first time in recent memory that a federal prorogation has been proposed to allow for a leadership contest (as Dalton McGuinty did in Ontario in 2012). The consistent thread throughout these stories was that prorogation remains an attractive political tool that serves the government’s interest, even if the Liberals currently deny they might use it.

What should we make of the use of prorogations?

Based on the above analysis, I draw three conclusions. First, the controversy surrounding Stephen Harper’s 2008 prorogation has permanently increased the political saliency of the practice. Every prorogation now brings increased media attention and potential for controversy, especially during minority Parliaments.

Second, when Prime Ministers Harper and Trudeau justified their prorogations, they offered two similar reasons, one technical and one policy-driven. The technical justification is that prorogation is an opportunity to recalibrate, refresh, or reset the government’s agenda. The policy-driven justification has been to use prorogation to focus on the economy. The consistent invocation of economic language to justify prorogation is yet another sign of the continued importance of economic issues to voters, regardless of the prime minister in power.

Finally, as a political tool, prorogation actually works, especially in minority settings. For all the sound and fury coming from the media and opposition parties, the 2008 coalition fell apart, the Afghan Detainees and WE Charity scandals faded into the background, and Prime Ministers Harper and Trudeau successfully reset their parliamentary agendas to purportedly focus on the economy. While the timing of previous uses may have marginally increased the political costs of prorogation, it has not stopped prime ministers from using it when politically expedient. There is no clear political cost for proroguing parliament.

At the moment, prorogation appears to be off the table due to the Liberals’ GST holiday legislation, which is making its way through Parliament. However, if Prime Minister Trudeau thinks prorogation is a tool that can gain the Liberals a political advantage in early 2025, expect him to use it—regardless of who will be prime minister when Parliament returns.