This article was originally published in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, May 30, 2024

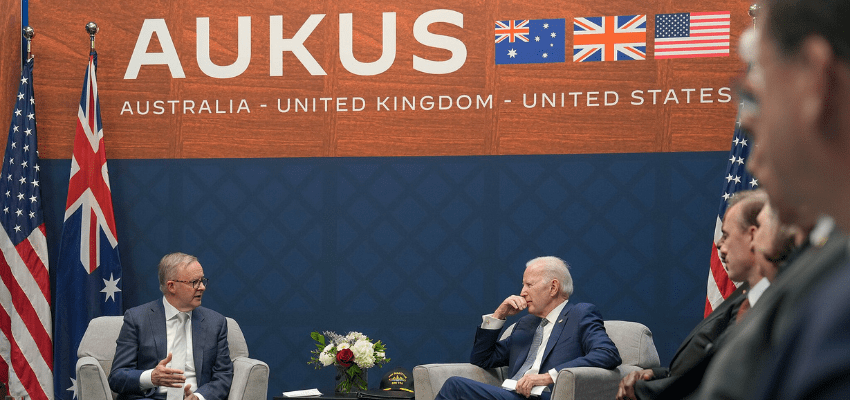

The minilateral partnership between Australia, the U.K. and the United States, or AUKUS, has garnered much attention of late. We already know China will paint it as a Washington-led alliance aimed at containing China based on outdated Cold War thinking.

These perfunctory criticisms should not stop these partners from advancing this consequential and innovative partnership. Still, AUKUS members will have to work hard in Southeast Asia to counter this narrative to secure direct or indirect support there.

To be clear, AUKUS is not a military alliance. It is not the beginning of an Asian or Indo-Pacific NATO. Essentially, it consists of three main components, or “pillars,” aimed at different objectives.

The first pillar is dedicated to aiding Australia in acquiring a fleet of conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines. The second pillar revolves around collaboration on emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence, cyber issues and electronic warfare. It also includes a third pillar — the production of legacy or older military-related technologies and weapon systems.

Where do allies of the U.S., Australia and the U.K., such as Japan, South Korea and Canada fit into AUKUS?

While AUKUS remains a trilateral partnership between Australia, the U.K. and the U.S., there’s flexibility for functional cooperation in the second and third pillars. This means that depending on the areas of focus, like emerging technology or the production of traditional military equipment, collaboration can occur smoothly and easily, akin to a “plug-and-play” system where components more easily integrate without much extra effort.

Several factors need to be considered:

First, the second and third pillars of AUKUS must show tangible results to determine who participates in specific areas of cooperation within pillar two.

Second, each country has its own unique strengths, comparative advantages and vulnerabilities in relation to Beijing. These factors will influence their decision-making regarding participation. For example, South Korea boasts significant technological advantages, but it is also vulnerable to economic coercion and other forms of pressure from China, prompting cautious decision-making.

Additionally, South Korea’s domestic political landscape is volatile. Changes in leadership could lead to shifts in positions regarding participation in pillar two, causing concern among AUKUS members about the stability of cooperation with South Korea.

This is not a trivial concern for AUKUS. Members witnessed the Moon Jae-in administration’s provocations and tensions with Japan, which strained trust and cooperation not only between Seoul and Tokyo, but also among the broader U.S.-Japan-South Korea alliance, impacting strategies toward North Korea and, in the longer term, China.

While South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol’s conservative administration has made significant efforts and done much to improve bilateral and trilateral relations, concerns persist, particularly given his recent electoral setbacks. There’s worry that a future progressive, China-leaning administration could reverse any progress made in pillar two cooperation.

In a worst-case scenario, advancements in emerging technology cooperation could be shared with a highly security-conscious Chinese government in exchange for economic incentives. This potential outcome raises significant concerns about the security implications of such cooperation.

Japan, in contrast, has the comparative technological advantages without the same vulnerability to coercion from Beijing or concerns that a change in prime ministers would change the nation’s strategic outlook. Except for the stalwart guidance of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, a change in leadership in the country in the arena of foreign policy usually means more continuity than change — a continuity charted by Abe.

In addition, Japan, with its sophisticated technological sector, its integral role in semiconductor supply chains, its commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific and its large conglomerates with substantial capital and human resources is well positioned to contribute to AUKUS’ second pillar as well.

Canada, another aspiring AUKUS so-called plug and player, also has comparative advantages. For instance, in the 2021 Canadian federal budget, the government proposed $360 million in investments over seven years to launch a National Quantum Strategy aimed at developing and strengthening the nation’s quantum research, quantum-ready technologies and ensuring its global leadership in quantum science. This shows that the nation is already dedicating resources that would contribute to AUKUS’ mission.

Additionally, the National Cyber Security Action Plan (2019-2024) provides an existing framework for Canada to contribute to the partnership. Through various initiatives, Canada has already invested in the legal, regulatory and strategic aspects of a national cybersecurity strategy. This strategy can seamlessly integrate with AUKUS initiatives at multiple levels.

Canada’s AUKUS participation challenge is less about resources and more about domestic politics, leadership and a bipartisan lack of focus on international affairs, including an outdated notion of being a middle power.

Pillar one’s focus on the transfer of nuclear-powered submarine technology to Australia will serve as a long-term deterrence capability allowing the three partners to deploy submarines for an extended period without detection. It represents deep and wide technological sharing in a very narrow space that will weave the defense industries and innovative sectors into a collaborative network that will enhance deterrence in the Indo-Pacific.

Japan, South Korea and Canada will likely never be welcomed into this pillar, an exclusive club that is unlikely to accept additional members. Membership requires a much higher level of secrecy, a proven track record of deep cooperation and stringent legal frameworks to protect such sensitive intelligence.

In the context of U.S.-China strategic competition, Beijing has a civil-military fusion (MCF) strategy. According to Audrey Fritz of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “The CCP’s strategy hopes to develop the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into a ‘world class military’ by 2049.” She says that, “Under MCF, the CCP is systematically reorganizing the Chinese science and technology enterprise to ensure that new innovations simultaneously advance economic and military development.”

Pillar two aims to prevent China from succeeding in its MCF strategy by outcompeting and dominating emerging technologies such as AI, quantum computing, cybersecurity and hypersonic systems. These technologies are viewed as crucial for shaping future economies, government relationships and individual privacy.

They will also be the foundation for much economic innovation. AI and quantum computing, for example, will enhance our capabilities in genomics, chemical engineering and electrical engineering, leading to the development of vaccines, medicines, genetic modifications and new materials.

These last areas are of particular concern. Those who dominate these technologies will determine how they are used and regulated and will likely be the primary beneficiaries of the profits from being first movers in these fields.

The third pillar also holds promise for Japan, Canada and South Korea. Each country has the manufacturing capacity to scale up the production of legacy military capabilities. These capabilities are important for replenishing supplies and munitions depleted while assisting Ukraine in its battle for survival against Russia. They can also create stockpiles that can be quickly delivered to high-priority areas if the need arises, such as Taiwan, Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia.

Tokyo, Ottawa and Seoul must demonstrate their value to the AUKUS minilateral partnership in pillars two and three, not only by their ability to plug and play, but also by showcasing the sustainability of their commitment, the additional value they can contribute and their dedication to maximizing AUKUS’ effectiveness in promoting a rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific.

Stephen R. Nagy is a professor of politics and international studies at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, a senior fellow at the MacDonald Laurier Institute, a senior fellow at the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.