This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, June 12, 2025

Canada has long fallen short of the military spending levels expected of a NATO member. The alliance calls on its members to allocate 2 percent of their GDP to defence, but in recent years, Canada has averaged nearly half that.

This, however, may soon change.

Earlier this week, Prime Minister Mark Carney announced that Canada will meet the 2 percent target by the end of the current fiscal year. If achieved, this would mark a significant increase from the current level of roughly 1.3 percent of GDP, bringing us to spending levels not seen since the late 1980s—and well above the low point of 1 percent of GDP recorded in 2013 and 2014.

But just as Canada appears poised to finally meet NATO’s previous target, the alliance itself seems likely to raise the bar to a new goal of 5 percent of GDP, potentially to be reached within the next decade.

While no formal decision has been made, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte held a press conference last week following a meeting of NATO defence ministers. During that meeting, ministers agreed to new targets and commitments to bolster military capabilities across the alliance. Among them was a proposed overall spending goal of 5 percent of GDP, with 3.5 percent earmarked for core defence expenditures. The remaining 1.5 percent would go toward broader security and defence-related industry and infrastructure.

Although details on what qualifies as infrastructure spending remain unclear, even the proposed increase to 3.5 percent for core defence represents a dramatic jump for Canada. The NATO plan also appears to include annual benchmarks to ensure consistent progress toward this target. While the secretary general proposed a 2032 deadline, some defence ministers are suggesting a more gradual timeline extending to 2035.

What does this higher military spending commitment mean for Canada’s public finances? It’s hard to overstate the fiscal challenge this would present—even with a longer deadline like 2035.

Canada’s military spending

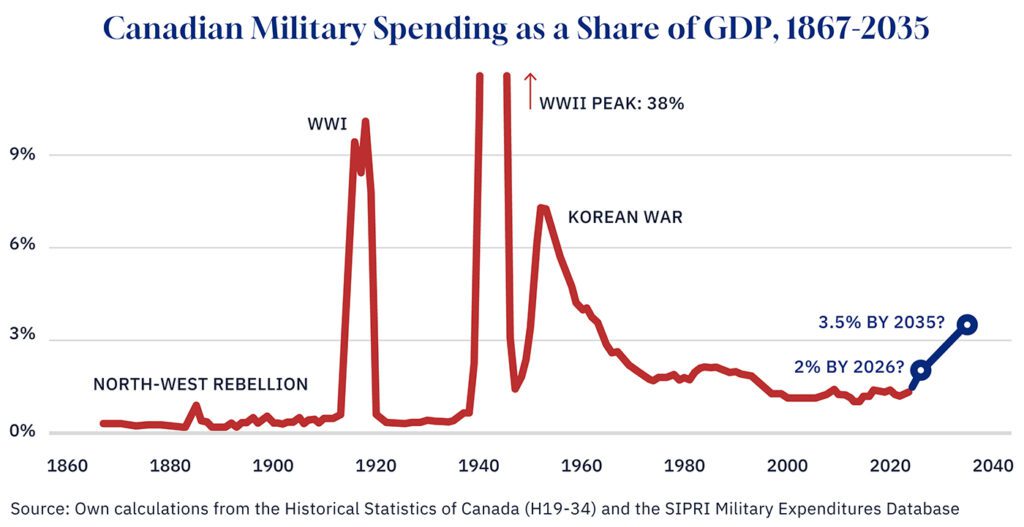

Some historical context may be useful. Drawing from various data sources, I’ve charted Canada’s military spending as a share of GDP since Confederation. For decades, spending was minimal—barely rising above 0.5 percent of GDP, even during events like the North-West Rebellion in the 1880s. That changed dramatically during the First World War, when spending peaked near 10 percent of GDP, and again during the Second World War, when it surpassed one-third of the entire economy.

An increase to 3.5 percent by 2035 would be the highest level since Prime Minister Diefenbaker was in office, and the sharpest rise since the Korean War.

In dollar terms, this would mean raising military spending from around $66 billion next year (to meet the 2 percent target) to more than $100 billion by 2030, rising to over $160 billion by 2035. Adjusted for inflation, the 2035 figure amounts to just over $132 billion in today’s dollars—more than triple the current military budget in real terms.

Whether Canada even has the capacity to scale up this quickly is a question best left to military procurement and operational experts. But such a large increase clearly has major implications for the federal budget.

Budget pressures

If Canada were to meet this target by cutting spending in other areas, non-military federal expenditures would need to shrink by nearly 3 percent of GDP by 2035. While substantial, that decline is comparable to the reduction seen between 2010 and 2015 and is slightly less than the cuts made during the mid-1990s program review led by then-finance minister Paul Martin. Still, it would be significant—especially given growing pressures on federal spending, such as increasingly generous transfers to seniors.

Alternatively, covering the cost through tax increases would require raising federal revenues to nearly 19 percent of GDP by the mid-2030s. That would return federal revenue levels to what they were in the early 1990s. For context, achieving this would be roughly equivalent to increasing the GST from 5 percent to 11.5 percent over the next decade.

Then there’s borrowing. If Canada chose not to cut other spending or raise taxes, debt would rise faster than the economy—a sharp departure from the current fiscal trajectory. Using the Parliamentary Budget Officer’s March baseline and excluding any new Liberal government platform commitments, I estimate that military spending of 3.5 percent of GDP by 2035 would push the federal debt-to-GDP ratio from about 42 percent today to 50 percent by 2035—that’s higher than the peak during COVID, and not a sustainable way to finance a military buildup.

A more dangerous world

Of course, any government is likely to pursue some combination of spending cuts, tax increases, and borrowing. That’s why the details in the next federal budget will be so important.

Unlike the past decade, the stakes are now much higher.

Rutte captured the urgency of the moment by saying:

There was such broad-based support today in the meeting, because allies understand this is necessary. And look at the Russian threat. The Chinese built up. We live in a different world. We live in a more dangerous world. It was the German chief of defence saying a couple of days ago that by 2029, the Russians might be able to mount a successful attack at NATO. So we are safe today, but if we don’t do this, we are not safe in the foreseeable future, and that’s why we have to do this.

Given the enormous financial stakes for Canada, a credible and detailed plan to finance this ambitious new target will soon be needed. Not just to meet our military and security commitments, but to clearly highlight the tradeoffs that doing so will necessarily involve.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum.