This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, September 21, 2023

This week, Canada’s prime minister, Justin Trudeau, accused India of involvement in the assassination of a Canadian Sikh activist on Canadian soil, triggering a broader deterioration in relations between Ottawa and New Delhi.

And when it comes to Canada-China relations, there has been a similar deterioration trend that began with the arrest by China of the so-called Michaels — Michael Spavor, a businessman, and Michael Kovrig, a former diplomat, both of whom Beijing accused of espionage. The two were arrested following the detainment of Huawei executive Meng Wangzhou in December 2018 at the request of the United States.

Today, serious accusations of Chinese electoral interference and threats against Canadian lawmaker Michael Chong have also translated into record-low favorability ratings of China in Canada and an atmosphere in which discussing anything about engagement between the two nations is radioactive.

Canada’s relations with Russia are no better as Ottawa correctly and courageously continues to provide deep support for Ukraine as it battles to maintain its sovereignty against invading Russian forces. Ottawa has maneuvered itself inadvertently into the position where it has alienated the first and second most populated nations on the planet and Russia, a declining but disruptive power determined to weaken the international rules-based order that Canada relies on for its peace and prosperity.

Also of major concern, in 2024 Canada may face a return of former U.S. President Donald Trump and his “America First” policies. So if Trump winning the presidency does come to fruition, Canada could be faced with a situation in which its most important economic, security and political partner may not be aligned with its goals, the second largest economy on the planet could become alienated and a country that is critical for Canada’s Indo-Pacific strategic engagement may become estranged if relations between the two countries deteriorate.

What is happening to Canadian foreign policy and why are some of its most important diplomatic relations spiraling in a negative direction?

Canada needs a realistic, pragmatic, and interest-based approach to how it’s engaging in the Indo-Pacific and more broadly on the global stage. Ottawa can no longer pursue foreign policy based on an outdated idea of a middle-power identity that is based on values-oriented diplomacy, a practice that evangelizes ideas and values that continue to be important for Canada’s domestic audience but not so much for those in the Indo-Pacific region.

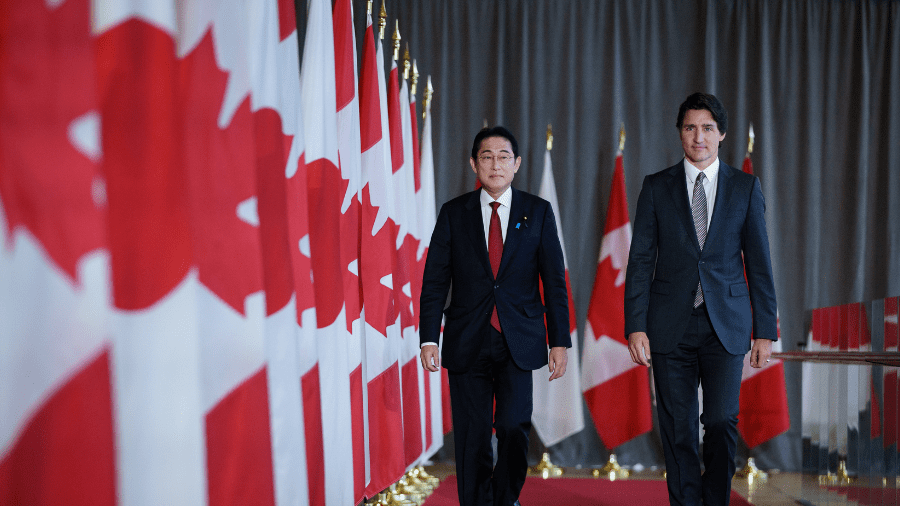

To avoid mistakes of the past and to be an effective and dependable partner in the broader Indo-Pacific region, Canada needs to strengthen partnerships with reliable allies and friends such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Singapore. These countries have similar democratic institutions, commitments to the rule of law, commitments to transparency and all share concerns about authoritarian overreach. They have also been more effective dialogue partners in many respects and have avoided many of the problems Canada has experienced.

What Canada can learn from Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Singapore is a more pragmatic, interest-based approach on how to deal with the challenges facing the Indo-Pacific region. What this translates to in terms of policy is focusing on engagement in such important matters as infrastructure and connectivity and partaking in pragmatic trade agreements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, including newer trade arrangements such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, all of which are nonbinding and detached from values such as human rights and democracy promotion, yet are still inclusive.

Canada can learn from Japan’s interactions with both China and India. In the case of China, Japan continues to engage through trade agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. It continues to build resilience into the relationship through the selective diversification of supply chains, such as the The Supply Chain Resilience Initiative. Japan also continues to enhance its deterrence through initiatives such as the new National Security Strategy, which calls for the doubling of defense spending by 2027

By enhancing its deterrence capabilities, Japan aims to put itself in a position where its key areas of concern, such as the Taiwan issue, open sea lines of communication, the disputes in the South and East China seas, including the Senkaku Islands, don’t get out of hand and remain stable, peaceful and are governed by international rules. It also hopes to maintain a viable security architecture with the support of the United States and its network of partners within the region.

When it comes to India, Tokyo recognizes the nature of the South Asian democracy and the trajectory of domestic Hindu nationalism. It also understands the challenges of its relationship with Pakistan. In addition, Japan proactively engages economically with India by investing in it as a counterweight against China’s economic might and by creating an environment where Japanese businesses can export goods to the Indian subcontinent.

Tokyo is also looking for a partner that can help build bridges in the developing world to ensure that the United Nations functions in a more equitable way. Tokyo certainly does not ignore the many domestic challenges that India faces but it does refrain from evangelical criticisms of New Delhi. It also strives for diplomatic solidarity within the developing world and fostering shared norms in the Indo-Pacific region.

Lastly, with regards to the United States, many countries within the region are worried about the potential re-election of Trump and what that might mean for alliance networks within the region, American commitments to conflicts such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and toward the dispute over Taiwan.

Rather than ignoring these issues or finding ways to deprioritize them, we see countries like Japan also investing in the U.S. relationship at the nonleadership level in terms of strengthening partnerships, business-to-business ties, university-to-university and think tank links. Japan’s rationale is that it can create a buffer against erratic leadership. These relationships can be used to provide an understanding of the island nation’s key role within the region and to convey information about the critical issues that it and the world face.

Under former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, the so-called Trump whisperer, we saw that this form of diplomacy was critical in helping the United States develop its own Indo-Pacific strategy. Abe was able to help convey to Trump the importance of some of the challenges within the region, including the dangers of North Korea’s nuclear program, challenges associated with Xi Jinping’s China and the critical nature of the Taiwan Strait situation, including their importance to both the Japanese and global economy.

As Canada seeks to reset its Indo-Pacific diplomacy and ensure that it is not relegated to foreign policy backwaters, it is going to need partners like Japan, South Korea, Australia and Singapore to help facilitate improved relationships and ties with India, China and the United States. The question is whether or not Canada will step away from its value-laden, middle-power approach that creates challenges in terms of sustainable, meaningful and engaged diplomacy within the region or will it take on a more pragmatic and realistic interest-based approach befitting its global status.

Dr. Stephen Nagy is a professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute; a senior fellow at the MacDonald Laurier Institute; and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.