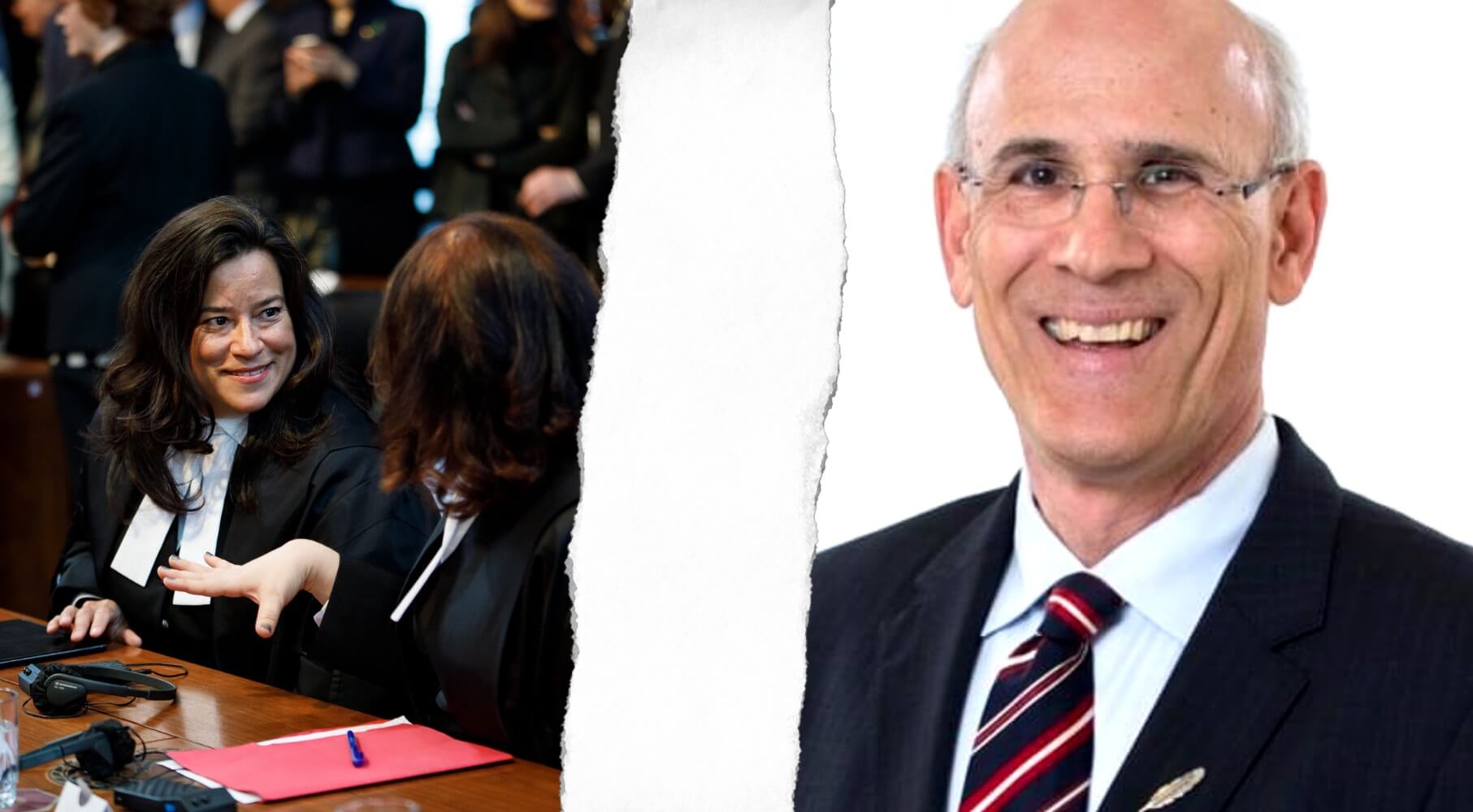

At a difficult time, Jody Wilson-Raybould made a courageous decision to put principle before political expediency, writes Brian Lee Crowley.

At a difficult time, Jody Wilson-Raybould made a courageous decision to put principle before political expediency, writes Brian Lee Crowley.

By Brian Lee Crowley, April 5, 2019

Last week Jody Wilson-Raybould, the former Justice Minister and Attorney General, surprised many observers by revealing that she had recorded a conversation between herself and the then-Clerk of the Privy Council, Michael Wernick. The recording was included as part of her supplementary written evidence to the Commons Justice Committee that heard her original testimony about Lavscam in late February.

The impropriety of the recording was highlighted by the prime minister, Justin Trudeau, as the headline reason why he was expelling Wilson-Raybould and her former cabinet colleague Jane Philpott from the Liberal caucus. According to the Prime Minister, this action by Wilson-Raybould broke the trust that must exist in order for members of the Liberal caucus to work together.

Trudeau qualified the recording as “unconscionable” and this view was echoed by numerous Liberal caucus members as justifying the expulsion of the two MPs. One MP qualified the recording of Wernick as “entrapment,” suggesting that Wilson-Raybould used her knowledge that a recording was being made to manoeuvre Wernick into making damaging statements that he might not have made “on the record.”

At first blush this argument has some credibility. Any enterprise, including a political party, must have a certain level of trust and mutual confidence in order to function, and this requirement is even stronger within cabinet, where ministers must have a minimum of trust in each other for government to work and decisions to be made. Moreover, Wilson-Raybould is a (non-practising) lawyer, and the legal profession has ethical rules against recording conversations without informing the other party.

Wilson-Raybould herself acknowledges that her action would, in normal circumstances, be considered “inappropriate.” The key phrase here is “in normal circumstances.” Was there something about the circumstances in which Jody Wilson-Raybould found herself which might ethically justify an action that ordinarily would be beyond the pale?

I think there is a strong argument that this is the case, and that Wilson-Raybould found herself in the unenviable position of having conflicting moral obligations. In other words, there was no course of action available to her that did not require her to neglect one ethical obligation or another. In these circumstances she had to make a choice which obligation to override. Did she make the right one?

Let’s look first at the conflicting obligations. We have already reviewed her obligations to her cabinet and caucus colleagues and as a lawyer.

Against these must be set her obligation as the Justice Minister and Attorney General to protect the integrity of the rule of law and prosecutorial independence at the heart of Lavscam and to denounce attempts to damage or twist these fundamental principles for improper and unethical reasons, even when those attempting to do so are her cabinet and political colleagues to whom she owes a duty of good faith collaboration. In my view, these principle are important and worth defending.

Let’s recall now that the Wernick conversation took place in mid-December and followed a months-long series of meetings and communications involving the Prime Minister and his associates on the one hand, and Jody Wilson-Raybould and her colleagues on the other. In those conversations the Attorney General and her colleagues, according to her own testimony and detailed contemporaneous notes, were very clear to the Prime Minister’s people that their attempts to press her to overrule the decision of the Director of Public Prosecutions in the prosecution of SNC-Lavalin were an improper attempt to override the principle of prosecutorial discretion. She also underlined over those months that she was striving to help the government avoid a scandal that would almost certainly arise if their efforts were successful.

By the time of the Wernick discussion in December, it would appear that Wilson-Raybould had concluded that her entreaties to respect the rule of law, constitutional principles and the reputation of the government were falling on deaf ears. Indeed, one of Trudeau’s most senior advisors had been completely dismissive of “legal technicalities” being used to obstruct the government’s political agenda. Finally, she was under the impression that if she did not play ball there was a serious possibility she would be fired as Justice Minister and a new minister put in place who might be more accommodating of the government’s agenda.

On my reading of the facts we possess, at this juncture Wilson-Raybould decided that her obligations of cabinet and caucus solidarity and so forth did not require her to acquiesce in what clearly appeared to her to be a conspiracy by senior government figures improperly to influence the justice system and to undermine the prosecutorial independence she was sworn to protect and uphold as Attorney General. In other words, her obligation to protect the integrity of the rule of law overrode the others. Given this unenviable choice, I hope I would have had the strength of character to do what Jody Wilson-Raybould did, which was to ensure that indisputable evidence of these efforts was preserved. Hence the recording.

Jane Philpott came closest to putting the recording in proper perspective. In her letter following her expulsion from caucus, she wrote that the government’s “approach now appears to be focused on whether Jody Wilson-Raybould should have audiotaped the Clerk instead of the circumstances that prompted Jody Wilson-Raybould to feel compelled to do so.”

Whether you agree with Wilson-Raybould and Philpott’s interpretation of what the government was trying to do, the fact is that the recording is a vital piece of evidence that supports their view and has helped to achieve the objective of making the government pay a political price for making every effort to violate important constitutional principles.

It is also not without irony that the tape revealed that Jody Wilson-Raybould was trying to protect the Prime Minister and the government from the consequences of a wrong-headed and improper course of action they seemed determined to pursue. Wernick, and others, heedlessly ignored her repeated warnings by continually pressing her to intervene because of the issue of job losses and potential political fallout in Quebec which she apparently had already considered and rejected as a ground for overruling the decision to prosecute SNC-Lavalin.

A basic truth of morality is that our obligations can and do conflict. The true test of character is how we resolve these conflicts. My view is that at a difficult time the Attorney General made a courageous decision to put principle before political expediency, and ultimately paid the price with, first, her demotion and, later, her expulsion (and that of her supportive colleague Jane Philpott) from the Liberal caucus. The focus now should properly be on the propriety of the actions of those who put her in the position where such a choice had to be made in the first place.

Brian Lee Crowley is managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.