[Ed: McGee’s call for union at Halifax, in the presence of Charles Tupper and Joseph Howe, outlining arguments he hopes “will be audible, within a month, to the farthest western settler who hears the wolf bark by night beyond Lake Huron.” Surveying the provinces’ vast geography and wealth of resources, McGee reviews the principle arguments in favour of union. Citing commercial reasons, McGee demands why we are “cutting each other’s throats with razors called tariffs.” Citing patriotic reasons, McGee calls for a new national sentiment to raise the tone of politics, asking: “why are our ordinary politics so personal; why are our great men sometimes found so small? Because we are sectional and provincial in spirit as well as in fact; we are not simply shut up in our several corners, but we sub-divide those corners into pettiest domains.” Invoking Magna Carta and the French civil law, McGee calls for Canadians to “crown the fair pillar of our freedom with its only appropriate capital, lawful authority, so that, hand in hand, we and our descendants may advance steadily to the accomplishment of a common destiny.”]

HON. MR. MCGEE said: – Mr. Mayor, Ladies, and Gentlemen– This meeting has grown out of a very simple circumstance – the desire of several gentlemen, some of them very old friends, to hear from a Canadian representative what was generally thought in his province, as well as what views he himself took, on the subject of the long-talked-of Intercolonial Railway.

The invitation was conveyed to me in the kindest terms, by gentlemen for whom I have the highest respect; but it would be folly in me to conceal that I felt a great deal of diffidence as to my own power to meet their expectations. I felt it not only from the nature of the subject to be spoken of – whose very magnitude was embarrassing – but also somewhat on personal grounds, as to what might be right and proper for me, as a Canadian representative, to say; but I nerved myself by saying, “If we can have no other direct intercourse, either of trade or travel, with our fellow citizens of Nova Scotia at present, at all events let us have the intercourse of free speech and courteous personal consultation.”

I propose then, to submit to you the views, so far as I understand them, of very many in Canada, on the subject of this projected Colonial connection, with some remarks on the same subject which, perhaps, are more personal to myself. We are of opinion, very many of us, in the first place, that we cannot go on much longer – not many months perhaps, not many seasons certainly – as we have been in the past. Great necessities have arisen within the present decade, both on this and the other side of the Atlantic, which seem to say to us, in Canada, and to all British America, “Look well to yourselves; consider carefully the times that now are; observe well that these are not the times of old; take counsel of your new Present as to how you may best confront your new Future.”

We may, ladies and gentlemen, be all wrong in thus translating into words the signs of our times, but with this warning voice ringing hourly in my ears, I cannot, for one, keep my eyes fixed only on local or sectional objects; nor shall I to-night treat the great subject you have called on me to discuss, in any local, or sectional, or one-province spirit. I should feel ashamed of myself if I were capable of mingling in the discussion of a subject of this description, anything – the least tinge – of the partisan; neither, I am quite sure, would you receive my arguments, if I were to calculate them exactly for the meridian of Halifax.

Moreover, I feel that I must speak of, as well as to, British America, – that the free press of Nova Scotia will carry what I may say to the free press of Canada, – and that the voice raised here to-night on behalf of Colonial unity, feeble as it is, will be audible, within a month, to the farthest western settler who hears the wolf bark by night beyond Lake Huron.

Now, what, in outline, is this British America of which we speak? We are four millions of nominal British subjects dotted over a seventh part of the continent. I say nominal British subjects, for we enjoy within ourselves absolute self-government, with an indefinite and sentimental, rather than a practical or onerous allegiance, to a distant, non-resident sovereign.

It is to be allowed, however, that there are two exceptions to this state of absolute self-government – the autocratic power of the Government of British Columbia,* and the close oligarchy of the Hudson’s Bay. And, as if to show how thoroughly the rights of the Crown are assumed to be extinguished in the soil of all these immense regions, we learn, only within a week, that that Hudson’s Bay Company have actually sold the proprietorship (and received the pretty luck-penny of £100,000 down) of somewhere about 500,000 square miles of Her Majesty’s dominions in North America, which the sellers pretend to hold in fee by a title derived from King Charles II. (*This complaint, perhaps overstated at the time, has since been remedied.)

Distant as that territory is from us, far in the future as its ultimate destinies may repose, I am sure the Imperial Government will have something to say about its sale, and that we in Canada will have something to say about its delivery. I know nothing but what has been stated in the newspapers as to this sale, but I instance it here, at once, to call attention to the statement, and at the same time to illustrate the anomalous state of our allegiance, where one private company can propose to sell and another to buy a British denomination as large as all England, France, and Germany.

A single glance at the physical geography of the whole of British America will show that it forms, quite as much in structure as in size, one of the most valuable sections of the globe. Along this eastern coast the Almighty pours the broad Gulf Stream, nursed within the tropics, to temper the rigours of our air, to irrigate our “deep-sea pastures,” to combat and to subdue the powerful Polar stream, which would otherwise in a single night fill all our gulfs and harbours with a barrier of perpetual ice. Far towards the west, beyond the wonderful lakes which excite the admiration of every traveller, the winds that lift the water-bearing clouds from the Gulf of Cortez, and waft them northward, are met by counter-currents, which capsize them just where they are essential – beyond Lake Superior, on both slopes of the Rocky Mountains. These are the limits of that climate which has been so much misrepresented – a climate which rejects every pestilence, which breeds no malaria; a climate under which the oldest stationary population – the French Canadians – have multiplied without the infusion of new blood, from France or elsewhere, from a stock of 80,000 in 1760, to a people of 880,000 in 1860.

I need not, however, have gone so far for an illustration of the fostering effects of our climate on the European race when I look on the sons and daughters of this Peninsula – natives of the soil for two, three, and four generations; when I see the lithe and manly forms on all sides around and before me; when I see, especially, who they are that adorn that gallery (alluding to the ladies), the argument is over, the case is closed.

If we descend from the climate to the soil, we find it sown by nature with those precious forests, fitted to erect cities, to build fleets, and to warm the hearths of many generations. We have the isotherm of wheat on the Red River, on the Ottawa, and on the St. John; root crops everywhere; coal in Cape Breton and on the Saskatchewan; iron (with us) from the St. Maurice to the Trent; in Canada, the copper-bearing rocks, at frequent intervals, from Huron to Gaspe; gold in Columbia and in Nova Scotia; salt, again, and hides, in the Red River region; fisheries, inland and seaward, unequalled.

Such is a rough sketch – a rapid enumeration of the resources of this land of our children’s inheritance. Now, what needs it, this country, with a lake and river and seaward system sufficient to accommodate all its own and all its neighbours’ commerce? What needs such a country for its future? It needs a population sufficient in numbers, in spirit, and in capacity, to become its masters; and this population need, as all civilised men need, religious and civil liberty, unity, authority, free intercourse, commerce, security and law.

As to population: the young ladies probably would not object that desirable young men should be somewhat more plentiful than they now are in these provinces. What would be a fair American ratio of population for our territory, covering, as it does, a third part of the continent? Twenty millions of a total would give us only five inhabitants to the square mile – our square miles are four millions – a degree of denseness which even a backwoodsman would not find inconveniently close.

Of the liberties enjoyed throughout all our part of the continent, it is to be observed, that with the temporary exceptions – Hudson’s Bay and British Columbia – they are in the hands of the people’s elected representatives. We need have no fear for our liberties if our representatives do their duty; but as to the other social and political needs of which I have made mention, that one about which I feel just at present most anxious, is authority.

I am told I have been taunted a good deal in some leading American journals for my frequently expressed anxiety on this head. I have been taunted as a Liberal, as if lawful authority were inconsistent with liberality; and, as an Irishman by origin, I have not been spared. I answer, Mr. Mayor, to all these flippant deliverances, that if I lived in a state of society in which liberty was in danger from the encroachments or excesses of authority, I should stand fast by liberty; but whereas, in our new world one plant is indigenous, and grows wild all round us, and the other must be introduced from afar and carefully cultivated, that other equally essential to the very existence of good government, I choose to concern myself most for that which we most need, leaving that which every public man is sure to cultivate, to the charge of its innumerable other guardians.

I answer, as an Irishman proud of the name, that in walking in this path I am in the right line of succession with the most illustrious Irish statesmen of the past – O’Connell, Plunkett, Curran, Grattan, and, above all, Burke; their trophies are found on every arch of the temple of the Constitution – their effigies are carved upon the very shrines of its sanctuary. They were statesmen whom the world knew; they were as jealous of authority as they were vigilant for freedom; what names has the school that opposes them produced to equal the last among that illustrious succession?

I do feel anxious for the consolidation of our provincial liberties – for the timely planting of a well-defined supreme authority among us, and, therefore, I adopt cordially the only practical form of arrangement which I can by any sign discover – the Union of all the Colonies, under the regency or vice-regency of a royal Prince, or other Imperial ruler. It will, perhaps, be within the recollection of those who hear me – I rejoice to see around me some of the same friends to-night – that several years ago, in this very room, I advocated, on commercial and political grounds, this same good cause of Colonial union. Is it not obvious, ladies and gentlemen, – you to whom I am all but a stranger, – that if I did not believe there were very good arguments in favour of such an union, I would not presume, after a lapse of years, to take up, on the same spot, the same cause, before the same community? These arguments, to my mind, are so numerous that I shall be obliged as formerly, to proceed by way of selection – touching only on a few of the most prominent and popular.

First. There is the argument from Association. What is taught us by the whole history of our times? That the greatest results are produced by the association of small means. In banking, in commerce, in science, association has been tried, and found in general to work wonders. The very Intercolonial Railroad, of which I am by-and-by to speak, is a proof of the absolute necessity of intercolonial association. Canada cannot build it alone; you cannot do it without Canada. What then is the obvious remedy? Is it not the union of our joint credit, skill, and resources for the accomplishment of a common purpose which singly none of us, nor all of us, can hope to effect?

Second. There is the commercial argument. Why should we, colonies of the same stock, provinces of the same empire, dominions under the same flag, be cutting each other’s throats with razors called tariffs? Here, for example, is my over coat of Canada tweed, which, imported into New Brunswick, is charged 15 per cent, and in Nova Scotia 10 per cent. – New Brunswick being 5 per cent worse than you are. Now, the British islands and all united states and kingdoms have long found it absolutely necessary to have within themselves the freest possible exchange of commodities. Why should not we here? Why should we not have untaxed admission to your 800,000 market, and you to your three million market? I confess I can see no good reason to the contrary. At the Quebec Conference,* over which I had the honour to preside, we decided that intercolonial free-trade should follow at once on the making of the railway, and I look back with satisfaction to having drafted that compact. (*The Intercolonial railway conference of September, 1862.)

Third. There is the immigration argument. I was much struck, speaking on this point, with a note to an article in, I think, “Macculloch’s Commercial Dictionary,” in which immigrants bound for these Lower Provinces were warned not to take shipping to Canada, because it was as hard to get here from Quebec to these lower ports, as from Liverpool! Practically, every one knows that an emigrant ship’s cargo is a mixed cargo. Say there are 400 persons aboard one of those ships arriving at New York, 100 will disperse towards the manufacturing districts of New England, another 100 to the mineral districts of Pennsylvania, while the other half will be divided between the landing-place and the agricultural West. The wide market makes the full ship.

The diversities of occupation swell up the aggregate of new labourers, and if we were united the inevitable result would be that each of us would secure a much larger share as parts of one great State, than either or all of us can command as separated and obscure provinces. In the past, what has been the fact? We gained but one million of British emigrants in all our provinces, from 1815 to 1860, while the United States gained three millions. Three of our natural born fellow-subjects passed us by for one that remained. They helped to swell and ranks and increase the riches of the Republic in a threefold ratio to ours, and they raised it in half a century to so high a pitch of property, that prosperity-mad, it spurned the immigrant, and madly menaced those ancient islands from which it drew its first being as well as the whole outline of its civilization.

Fourth. There is what I shall call the patriotic argument – the argument to be drawn from the absolute necessity of cultivating a high-hearted patriotism amongst us provincialists. I speak without offence – with an eye to my own part of the country as well as any other – when I ask, why are our ordinary politics so personal; why are our great men sometimes found so small? Because we are sectional and provincial in spirit as well as in fact; we are not simply shut up in our several corners, but we sub-divide those corners into pettiest domains. With us, in Canada, there is a Toronto party, an Ottawa party, or a Quebec party. It was said of old, “Octavius had his party, Antony had his party, but the Commonwealth has none,” – and thence the decline and fall of Rome.

Are we capable in these lands of being inspired with sentiments of a saving patriotism? Are we capable of being kindled into a common passion for a common cause? Capable, I mean, of being made so in advance of events which might prevent the sacred fire from warming or guiding us on in a common contest. I don’t ask you how you would feel down here, on the Gulf or the Bay of Fundy, if you heard Quebec was besieged – that Quebec had fallen. I have no doubt whatever that you would feel a common calamity then, or that we would equally feel it on the St. Lawrence, if we heard that Halifax had been attacked by a fleet of Monitors, or that a hostile force had crossed the St. John. But it might be too late then to remedy the evils of isolation – it would certainly be too late to avert some of the worst of them. Is it not the part of true wisdom now, while we yet have time – now while the actual emergency is not yet upon us – is not this is the opportunity, since we must stand or fall together, if war comes, to consult how best we may conduct ourselves by each other, and towards England, so that we may stand, and not fall? So, that England may trust, and not distrust us?

Fifth (and for the present lastly). There is the argument of political necessity, arising from the state of our next neighbours. I am not about to say one word – I can lay my hand on my heart and declare that I do not believe I have uttered one word since the commencement of the unhappy civil war – to irritate or embitter republican feeling against us. I deprecate all intermeddling on our part in that war, in which we were commanded to observe a strict neutrality, in spirit and in letter, and I would implore every man who values the blessing of good neighbourhood not wantonly to aggravate the existing bad feeling. In this case, certainly, they who “sow in bitterness” can hardly expect to “reap in joy.”

I say this in no idle hope or wish to conciliate northern prejudice in its present temper; I say it as a lover of peace and a hater of causeless warfare; but if war must come upon us here, in these long peaceful regions, I have no doubt, for my part, that all our people of every race and creed and class, will be found serried like iron in defence of our own freedom and the imperial connection which ensures it to us.

I dare not pretend to predict the end of the present contest; but however otherwise it may end, there must long continue a powerful military element, active and unexhausted. If the South be subdued, armies will be needed to hold it down; if the combatants separate, each will arm his frontiers and replenish his arsenals. It seems to me a question mainly, in this light, whether we shall have two military independencies or one between us and Mexico? If two, then it would be but natural that they should turn back to back – as to their aggressive movements – the South marching south, the North marching north. You remember Pope’s lines –

“Where is the North? In York ‘tis on the Tweed!

In Scotland ‘tis the Orcades; and there –

‘Tis Greenland, Zembia or the Lord knows where!”

Where would be the limit of the North then? I put the question through you and through the press of Halifax to all British America. Where would be the limit of the North, in that contingency? I leave the answer to each for himself, while I, for my part, answer, that if these Provinces are united in good time, for mutual support, counsel, and protection, I do not fear that they would be able to hold their own against all comers.

So much for the obvious arguments in favour of Colonial union; the argument from association; the argument from Commercial advantages; the Immigration argument; the Patriotic argument proper; and the argument drawn from the proximity of danger, from the circumstances existing in the neighbouring States. Here, I quit the general subject and now beg to come directly to the topic most immediate – the necessity – the absolute necessity on all these grounds – of an intercolonial railroad.

I am not here to discuss, nor would you care to hear, a detailed discussion of the long-continued negotiations on this subject. But I must take this opportunity of declaring, as one cognisant of all the facts (I think I may say so) of the last negotiation, that the imputation of bad faith, so freely made here and in England, against the Canadian delegates who went over last year, is a groundless and undeserved accusation. I do not desire to be at all disputatious; I think I may say I am impartial in the matter – for with some of the gentlemen as responsible as I was for that negotiation, on the part of Canada, I no longer act; but whether with them or against them, I utterly deny for them and for Canada, the imputation of bad faith.

I will tell you candidly how the question is viewed in Canada. Leading public men of all political parties admit that is most desirable, if the liability could be limited, that this great work, so long projected, should be undertaken. There is no parliamentary party, there is no Cabinet possible, that would say, or dare say, – “no railroad – no connexion – on any terms.” At the same time, the non-political men of influence – many in Eastern, and many more in Western Canada, many also of the constituencies, are not favourable to the project at all – certainly not to it as a Government work; they were so scorched by the Grand Trunk, they say, that they dread the fire of any other railroad.

In some respects, the popular prejudices against the whole thing are not unfounded; but in others, I am bound to say their only basis is a melancholy want of information, as to the extent, resources, and capabilities of this part of British America. The prejudice really, in these last aspects, is against New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, as countries, rather than against the road. People say, “What do we want with a railway down there? No one lives down there. We have no trade, we are never likely to have any trade with them. The land is a wilderness, and the winter would render the road impassable.”

This is, of course, gross assumption; but has not every great improvement to encounter just such assumptions? Was not the reciprocity Treaty carried against prejudices as perverse – as contrary to the facts? Was not the Union of the Canadas themselves a conquest over far worse prejudices? And it is because this want to knowledge an only be combated by intelligence, that I am a volunteer in the needful work of making the different provinces acquainted with each other. It is not harder to pull a prejudice than to pull a tooth – and the unsounder it is, the more necessary to have it out. I invoke intelligence on our side.

To combat against such lamentable misconception everything helps, from a weather almanac up to a Scriptural quotation, and even if the railroad should not soon go on the labours of intelligence will not be altogether lost. In one sentence, ladies and gentlemen, I do not hesitate for my part to say, that if it can be shown to the satisfaction of the people of Canada that the country through which the road would pass, is naturally rich for three-fourths of the way in soil and in minerals; if it can be shown (as is the fact) that, thanks to your warm-hearted neighbour, the Gulf Stream, your winters are far milder than ours, either in Lower or Central Canada; if it can be shown that the liability could be limited to three, or even three and a half millions sterling; if it can be shown that private capitalists able and willing for the work might be found to undertake it; then, ladies and gentlemen, on all these showings, which I myself believe to be perfectly possible, I have no hesitation in saying that the people of Canada, for their own sakes, and for the sake of British connection, would sustain their government in entering at once on this great work, and thus rendering practicable the so desirable Union of all the colonies.

Here, perhaps, I best may pause. A very few words, and I am done.

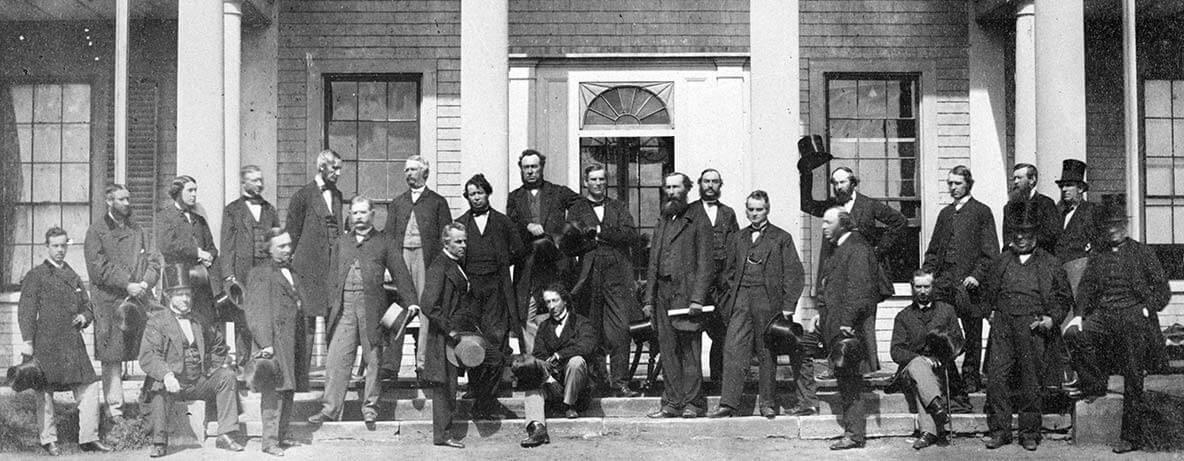

This great project of Union was, as you know, endorsed by Lord Durham, the Imperial High Commissioner to these Provinces, in 1838. Of late years it had been sustained through all vicissitudes, on this side of the Atlantic, mainly by the advocacy of the many able public men Nova Scotia has given to political life. Some – the chief among them (turning to Messrs. Johnson, Howe, Tupper, Henry, &c.) I have the satisfaction of seeing here, beside me. They are here, irrespective of party, and I trust I may add, that I have endeavoured, not only out of care for the subject, but from respect to them, to treat the subject wholly without allusion to party, or local distinctions.

In the presence of the great subject as I contemplate it, the lines of party are effaced and disappear. I endeavour to contemplate it in the light of a future, possible, probable, and I hope to live to be able to say positive, British-American Nationality.

For I repeat in the terms of the question I asked at first, what do we need to construct such a Nationality? Territory, resources by sea and land, civil and religious freedom – these we already have. Four millions we already are – four millions culled from the races that for a thousand years have led the van of Christendom. When the sceptre of Christian civilisation trembled in the enervate grasp of the Greeks of the Lower Empire, then the western tribes of Europe, fiery, hirsute, clamorous, but kindly, snatched at the falling prize, and placed themselves at the head of human affairs. We are the children of these fire-tried kingdom-founders, of these ocean-discoverers of western Europe.

Analyse our aggregate population: we have more Saxons than Alfred had when he founded the English realm; we have more Celts than Brien had when he put his heel on the neck of Odin; we have more Normans than William had when he marshalled his invading host along the strand of Falaise. We have the law of St. Edward and St. Louis; Magna-Charta and the Roman Code; we speak the speeches of Shakespeare and Bossuet; we copy the constitution which Burke and Somers and Sidney and Sir Thomas More lived or died to secure or save.

Out of these august elements, in the name of the future generations who shall inhabit all the vast regions we now call ours, I invoke the fortunate genius of an united British America, to solemnise law with the moral sanctions of religion, and to crown the fair pillar of our freedom with its only appropriate capital, lawful authority, so that, hand in hand, we and our descendants may advance steadily to the accomplishment of a common destiny.