[Ed: McGee tells Quebec Conference delegates to look around – and they will find “reasons as thick as blackberries” for a union of the provinces: “This was not a time for questions about creeds, or origins, or races, but a time either to save or ruin British North America.” Canadians, he says, are building their new constitution “on the old foundations” of Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights, not “a plagiarism of republicanism.” Today, McGee’s declaration that Canadians are one united people that resonates strongest. Reaching across religious divides, McGee declares bigotry in Canada can become a thing of the past, with religious and political liberty. Canadians will show themselves fit for self-government “…by allowing every man of every creed and sect and race to manage his own affairs in his own way, and to wash his own dirty linen in his own back-yard, so that it did not trouble the neighbours or disturb the peace of the community.”]

Mr. McGee said he had no intention at that late hour, and after their long sitting in Conference that afternoon, to detain them. When they were in the Lower Provinces their hospitable entertainers, many of whom they were glad to see to-night, were, on all occasions, pleased to hear Canadians speak and themselves to listen. He thought, as far as he (Mr. McGee) was concerned, he would best discharge his duty in showing himself a good host by being a good listener.

However, as the Canadian politician who earliest made the acquaintance of some of the gentlemen now here, as one who had been, in an humble way, a pioneer of this gathering of the British North American family, he could not, as the only one of the members for Montreal present at this moment, who had not spoken, allow the meeting to separate without giving his hearty endorsement to every word of welcome addressed from the chair and by the various speakers to their friends from the coast Colonies.

They were welcome to Canadians as fellow-subjects long estranged from them, and now, he hoped, about to be united. They were welcome to Canadians on their own account, as accomplished gentlemen, and of their accomplishments and powers the meeting had had this evening some evidence. They were still more welcome to Canada on account of the colonies of Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and of the communities there which they represented. As far as he was concerned, he would make no mystery of what brought them here, or of the business with which they were engaged. They were doubly welcome, to himself, as one of the representatives of the first city of British North America, for the work of union in which they were now engaged.

He was told that some of the citizens had often asked, Why this Conference at Quebec with closed doors? Why all this mystery; why this gathering together from the ends of British America of all the leading public men? Why were the several Governors of the Provinces eastward deprived of the benefit of the advice of their responsible advisers, that they should be thus gathered together at Quebec holding close council together? Parties said they elected these gentlemen to administer the government and laws as they exist, and not to frame new constitutions. Why, it was asked, had these gentlemen come here to sketch out, as was reported, the lines of a new constitution?

If asked the reason why, he would give the reason in one word, the same which the visitor to St Paul’s was called upon to read on searching for the monument of Sir Christopher Wren – circumspice! Look around, and they would see the reasons for this gathering. Look at the valleys of Virginia, at the uplands of Georgia; look around in this age of earthquake and political perturbation in North America. Look at the men in these Provinces who were called its statesmen, whom Great Britain had warned solemnly and repeatedly through the press and Parliament, and by direct official notification, that if the Provincials did not provide adequately for the exigencies of their present new condition, England would hold herself blameless for the consequences. Why, she had given us all warning that things could not go on in future as in the past. If they wanted to see reasons for the present Conference let them look across the border, and they would find reasons as thick as blackberries why they should meet as they did and engage in the work which had for some time occupied them.

It was now necessary, having gone so far, that they should have with them, the cordial and united support of the public opinion and the public voice of the great city of Montreal, the heart and brain of Canada. He trusted, too, they would have the support of the majority of all the intelligent people of Canada, of whatever origin, creed, or race. This was not a time for questions about creeds, or origins, or races, but a time either to save or ruin British North America. If its fate were not decided within this decade by its own act, in one sense assuredly it would be, and perhaps not to their satisfaction.

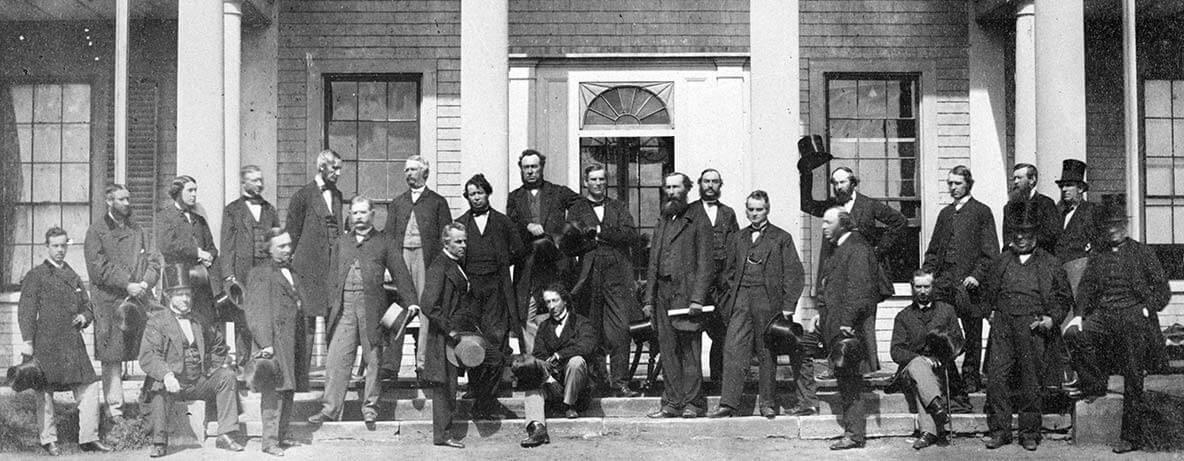

If the thirty-three delegates had presumed to go into the Chamber in Quebec to sketch an outline to be submitted to Her Majesty in Council and the Imperial Parliament, before which submission it was not right it should be submitted in any kind of detail to the people of these Provinces – if they had gone into that room in a time of profound peace to sketch a new basis of constitution for these Provinces – they found their justification in the circumstances, in the peculiar position, in which the British American Colonies stood towards Republican North America, and in the intimations, official and unofficial, respecting our duties as to self-defence, conveyed to us for the last three years from the most undoubted sources – from the government of the Empire itself.

The Conference had acted, not in an empirical spirit – they had not gone into Council to invent any new system of Government, but had entered it with a reverent spirit to consult the oracles of the history of their race. They had gone there to build, if they built at all, on the old foundations. They desired not to build an edifice with stucco front and lath and plaster continuations, but a constitutional edifice upon a basis of solid British masonry, sold as the foundation of the Eddystone Lighthouse, which would bear the whole force of the democratic winds and waves, and the corroding political atmosphere of the New World, and which they hoped would stand for ages, a vindication of the solidity of their institutions and of the legitimacy of their origin.

In their (the British N.A.) political architecture, he trusted they would vindicate the honour of the races from which they sprung, the Norman, the Saxon, the Celt, the homely, vigorous, fearless Scandinavian, and all the races that had gone to make up the great concrete called the population of the British Empire. He trusted that the British N.A. political architecture would not be a plagiarism of republicanism, and not fulfil the predictions so freely showered upon them by some of the New York journals, that the proposed union would be simply democracy in disguise; but that we should not only acknowledge the monarchical principle, but construct an edifice with British connection as the corner-stone, and freedom as the main wall of the structure; and make the people feel their freedom was connected with a due respect for authority and the throne, as well as for those who represented here authority and the throne.

In answer to the well-wishing editor of the New York Albion, who had cautioned Canadians against premature rejoicings over the degree of success they had attained, as they had done with regard to the laying of the Atlantic telegraph cable a few years ago, he (Mr. McGee) would venture to assure the editor they had not been experimenting and sounding out of their depth as those who laid the cable did. The members of the Conference had not been together so far without having a fair indication of what each other’s opinions and sentiments were. They wanted no electrical stimulus from England, having only to touch Magna Charta and the Bill of Rights to receive all the inspiration or impulse they wanted in their present labours. So long as they had that electrical inspiration in their libraries, at their sides, they would always know what was thought in England of the work they had been doing at Quebec.

In going back to their constituents, he said to their honoured guests, not as an Upper Canadian or as a Lower Canadian, for he had always said the Province line was abolished before he came to Canada, and if it was never drawn again till he drew it, either socially, politically, or any other way, it would remain undrawn long enough – he said to them, not simply as a citizen or representative of Montreal, nor even as an inhabitant of Canada, but as one who desired, and had laboured, in his humble way, to bring about this very spectacle which they to-night witnessed – he would say fearlessly and unreservedly on the part of Canada, that Canada, he firmly believed, sought this alliance, not from mercenary motives, but from a sentiment of common defence.

If they, on their part, came into this union, as he thought they would, well dowered and in such a manner that no one of the partners could ever upbraid them with their having come in a subordinate position – they could say that if Canada desired this union, which he believed she did, although the public mind of the country was not yet fully formed upon the subject, she went into it for no selfish small, or mercenary purpose; and they could say for the public intelligence of Canada, and especially for the city of Montreal, that we were year by year, and every year, becoming more enlarged and liberalised in our views; that we were becoming less angry and hostile as sects and classes; that we were becoming better friends, and that now all men agreed that we could go where we liked on Sunday, or nowhere at all, if we liked that better; but that, at all events, on week-days in our business and social relations, we bore ourselves as one people, with one heart and mind, for the commonweal.

They could say that in Canada religious bigotry was at a discount; and if they wished for illustration, he could point his finger and show where the bigot had withered on his stalk, and where once he had a great show of power and influence, now were “none so poor as do him reverence.” Bigots of all kinds, Catholic as well as Protestant; bigots of all classes, on all sides; bigots of race, who believed that no good could come out of the Nazareth of any other origin but their own – their day of small things – God knew how small – had passed for ever in Canada. Every many was willing to respect every other man’s convictions.

We had, at least, reached that degree of self-government, and shown ourselves to be in the best sense civil and religious freemen, fit for self-government, by allowing every man of every creed and sect and race to manage his own affairs in his own way, and to wash his own dirty linen in his own back-yard, so that it did not trouble the neighbours or disturb the peace of the community. He thought their guests from below might assure their neighbours when they returned, that if they united with us they would find all that in Canada – religious combined with political liberty.

He was sorry they had been so long confined in the political laboratory at Quebec that they would not have time before the necessities of the season compelled them to return to their homes to see what went to make up this great Province – great in resources, great in extent, but greater still in the promise it seemed to hold out, that here in British North America we should establish true freedom – not freedom fair without but foul within, but that true freedom that gave every man his private and personal rights, consistent with the private and personal rights of others. They might say to their constituents, that if Canada went into this union she went into it mainly with a view to promote the common prosperity, to secure the common safety and to establish the common liberties of all British North America.