While a severe blow for its workers and the whole community, GM’s closing of its Oshawa assembly plant is hardly surprising. The harsh consequences of this ending requires a clear understanding of why GM reached this decision.

However, because the losses from the closing are so painful, every interest group, including unions, various levels of government, and GM management is putting out its own spin. None of them is being entirely honest and transparent.

Eliminating the last jobs at Oshawa is the culmination of a long downward spiral. The number of jobs at GM’s assembly complex fell 90 per cent from its peak of 23,000 in the 1980s to just 2,500 when their termination was announced.

Union leaders and politicians were well aware Oshawa’s future was in doubt: the federal innovation minister says he started every conversation with GM by anxiously asking, even before saying hello, “How’s Oshawa?”

Who’s to blame? The fault certainly does not lie with the workers, among GM’s most productive. Managerial greed was not the main factor, since 25 per cent of executives also will lose their jobs.

Neither are carbon taxes, nor is the tariffs on steel and aluminum at fault, since GM also closed car plants in the U.S. Nor can we blame either U.S. protectionism or the North American trade deal, because GM is not shifting car production to the U.S. or Mexico (while Canada was hardly singled-out for cuts, it cannot expect to be spared when the U.S. Midwest was also hard hit in this round of closures).

A shift to electric and environment-friendly vehicles, cited by GM in its press release, is not the motivation since one of the plants closed produced the Volt; in fact, concentrating on trucks and SUVs makes GM less environmentally friendly.

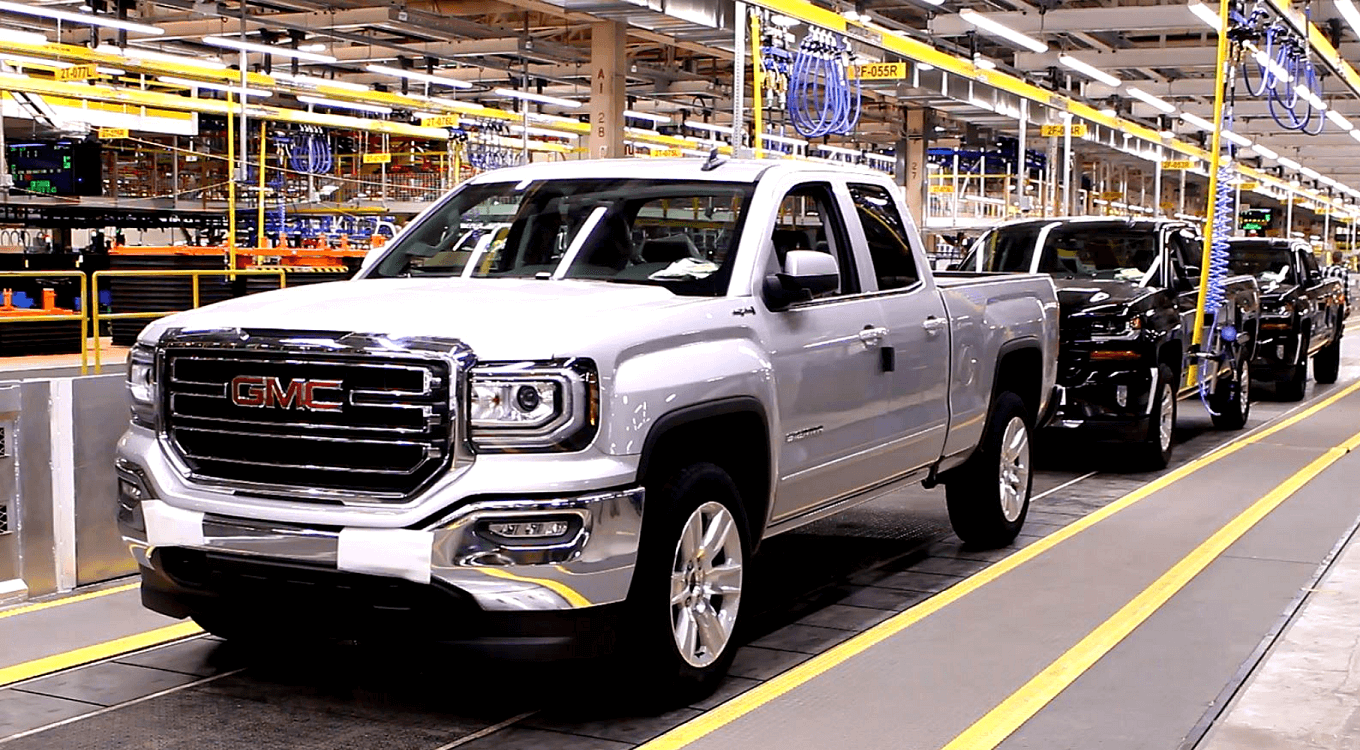

All of GM’s closings last week reflected a decision to stop producing passenger cars, including two other car assembly plants in the U.S. as well as two related transmission plants. GM is following Ford and FiatChrysler in largely abandoning the market for passenger cars to Japanese and European producers (GM will continue niche production of the Camaro).

Recent sales trends made GM’s shift in strategic focus inevitable. Demand for most GM passenger cars has fallen by half since 2014, even as sedan sales held up for overseas producers.

While GM’s Oshawa plant remained highly productive, this matters little when demand for its product is falling rapidly. The shift in consumer tastes to Japanese and European passenger cars has been ongoing for decades. It is not something that governments can, or should, regulate.

The core of GM’s long-term strategy is that it will only produce trucks and SUVs, because they are protected from overseas competition by high tariffs and because the Big Three firms have a stronger brand in these markets than overseas producers.

Many people do not realize trucks and SUVs imported from overseas face an average 20 per cent tariff, while passenger cars face minimal tariffs. GM could continue to compete with Japan and Europe in the low-margin market for sedans, but decided to maximize its return on capital by focusing on trucks and SUVs.

The closure of the Oshawa assembly line reveals the failure of a number of tactics. One is the union’s posture of endless bluster and confrontation, which may play well with the rank and file but is increasingly outdated as North American auto production clearly moved south to non-union workplaces.

Management did not stay abreast of changing consumer preferences and the best management techniques. The long-term innovation strategy of federal and provincial governments has failed to keep up with the rapid shifts in auto technology, which is becoming software packaged on wheels.

Most importantly, governments failed to realize that regulations and taxes raising the costs of producing in North America ultimately would drive firms to concentrate on high-margin vehicles that could absorb these costs.

This long-term shift in the focus of North American-based producers was reinforced by keeping high tariffs on trucks and SUVs produced overseas. The unintended result today is that North American-based firms soon will no longer make passenger cars in Oshawa or anywhere else in North America.

Philip Cross is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and former chief economic analyst at Statistics Canada.

With demand for its product is falling rapidly, the closure of GM’s Oshawa assembly plant is no doubt tragic, but it is hardly surprising, writes Philip Cross.

With demand for its product is falling rapidly, the closure of GM’s Oshawa assembly plant is no doubt tragic, but it is hardly surprising, writes Philip Cross.