The bottom line seems to be—thus far—that notwithstanding thicker post-9/11 borders, the Great Recession, and two years of Trump, life does go on, writes Stephen Blank.

The bottom line seems to be—thus far—that notwithstanding thicker post-9/11 borders, the Great Recession, and two years of Trump, life does go on, writes Stephen Blank.

By Stephen Blank, July 16, 2019

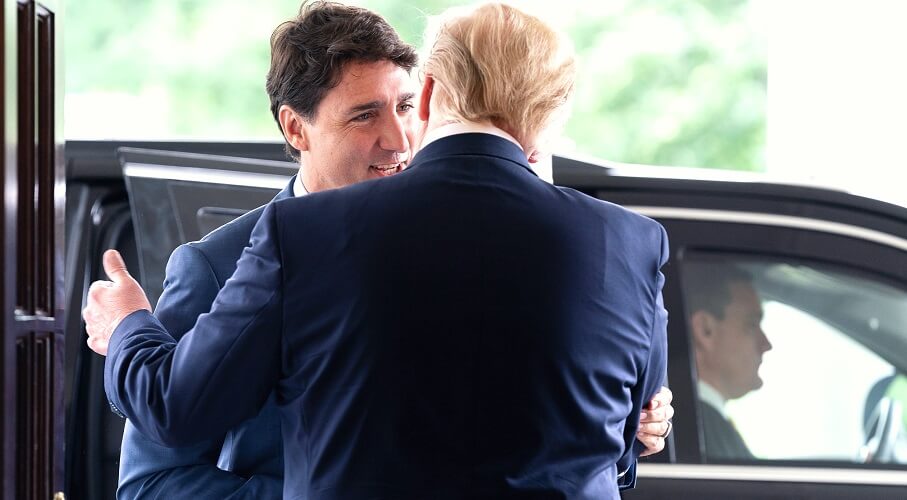

Senior Ottawa policymakers were undoubtedly shocked in the first months after the U.S. presidential election. Indeed, the Trudeau government has seen many of its global aspirations upset by Trump, from the Trans-Pacific Partnership to the Paris climate accord to the Iran nuclear deal, to say nothing about hopes for better relations with Washington.

NAFTA renegotiations were characterized by narcissistic performances and threats hurled by the White House and frantic tap dancing by Ottawa. And, even after the dust has settled on these negotiations, doubts still continue to linger—as shown by Trump’s “Buy America” provisions, which was recently blamed for Bombardier job cuts in Thunder Bay, Ont.

Still, seen through the dust raised by Trumpian blasts, life has gone on and bilateral economic ties remain reasonably robust.

Canada remains, if not the U.S.’s largest trade partner, then tied for first place with China. It is the U.S.’s largest export destination. Moreover, U.S. exports of goods to Canada increased in 2018, much as they have done so since the end of the Great Recession. The stock of U.S. foreign direct investment in Canada continued to grow as well, and Canadian direct investment in the U.S. did the same.

The bottom line seems to be—thus far—that notwithstanding thicker post-9/11 borders, the Great Recession, and two years of Trump, life does go on.

But does this mean we are ready for the issues barrelling down on us in the near future—the impact of technological change, the impact of climate change, the impact of demographic change? Here, collaboration may be vital to managing these issues.

Technological change is surely transforming every dimension of our lives. In just one dimension, it will have a profound impact on the systems of supply, production, and distribution that drove deeper North American integration since the 1980s. Think of autos, which became the symbol of collaborative, cross-border supply, and production systems. The old familiar corporate faces may not be the leaders in the emerging transportation industry and habits of cross border relations may be shattered. The same is true for electronics and telecommunications.

How do we build the widest base of co-operation in this new world? How can we keep entire regions from being left out in the transition to this new environment? Technological change must also be supported by energy and infrastructure.

With regard to energy, Canadians, Americans, and Mexicans alike benefit from North America’s deeply integrated oil, gas, and electricity systems. Increasingly, the main energy issue for North America will be to determine an energy mix that optimizes availability, cost, and sustainability for future generations. How do we view energy in continental terms rather than in separate national boxes?

Competitiveness requires efficient, safe and sustainable transport, logistics systems and border crossings. But North Americans face a tremendous infrastructure crisis. Transportation of goods and people is limited by collapsing infrastructure; pipelines, water systems and electric wires are weakening; broadband carriers are reaching capacity; and sea- and airports are falling behind international competitors.

Environmental threat cannot be discussed as three separate national issues. Climate change does not stop at the Rio Grande or the 49th parallel; it does not recognize national borders. We must learn to think of our water and agricultural resources and systems as continental in nature. We must deal with climate change in a continental framework, and develop policies for mitigation and for adaptation in a common framework. Easy to say.

North America’s extensive demographic change is also imposing hard limits on policies for economic growth and fiscal balance. Population movement has been the most visible and politically potent dimension. But we are all experiencing high levels of internal migration; people seek to follow jobs, creating new metro regions on one side and depopulated areas on the other. Aging is going to be an increasingly powerful driver of change. We face growing imbalances of the supply of medical and educational resources and changing levels of demand for these services.

Finally, we confront a growing need for a North American strategic vision for dealing with the Arctic, NATO, China and Central America, as well as adapting the postwar-era international institutions to new global realities.

How do we build collaborative solutions to these issues that affect us all?

Political observer Chris Sands writes, “the USMCA negotiations have done serious damage to US-Canada relations that will take time to repair. Among the general public in Canada the worst damage has been to trust.”

Big questions lie ahead. Was Trump an anomaly or does he represent a resurgence of America’s inward, isolationist, nativist personality? Would a Democratic President make knitting back relations with Canada a top priority, and would he or she seek to build the means to confront these powerful issues facing us? Stay tuned.

Stephen Blank is a senior fellow at the University of Ottawa’s Institute for Science, Society and Policy and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.