This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, February 4, 2026

Rising separatist sentiment in Alberta and Quebec is back in the spotlight—and the economic stakes are substantial. New estimates, outlined below, suggest nearly 2 million jobs across Canada depend on interprovincial trade with these two provinces, and tens of billions of dollars or more could be at risk if either seriously pursues separation.

The renewed attention follows reports that an Alberta sovereignty group met with individuals in the U.S. federal government and is seeking $500 billion in credit for a future independent Alberta.

At a meeting between premiers and the prime minister last week, the premier of British Columbia called it treason, while Manitoba’s premier (in more measured terms) warned of U.S. attempts to destabilize Canada during an unprecedented time.

Meanwhile, there is a potential resurgence of Quebec separatism with the Parti Québécois currently leading in the polls. Ontario Premier Doug Ford warned of “a disaster” if they were to form government.

Of course, separatist sentiment isn’t new. Since Confederation, some provincial leaders have occasionally expressed a desire to leave Canada. But with Quebec possibly electing a separatist government, and Alberta potentially holding a referendum, it’s worth taking a closer look at what’s at stake—especially as Canada’s economy is already navigating high uncertainty and weak productivity growth.

In earlier work published in The Hub, I explored the long-term economic challenges Alberta might face were it to separate. Using estimates based on the United Kingdom’s experience with Brexit, the evidence suggests that increased trade costs and a reduction in productivity would significantly weaken the province’s long-run outlook.

But there are more immediate and tangible risks, particularly to jobs and incomes.

Millions of jobs depend on interprovincial trade

Trade between Alberta and Quebec and the rest of Canada is substantial.

Any disruption to those flows, either through actual separation or growing uncertainty, would reduce demand for traded goods and services and harm workers throughout the country.

There is no official estimate of the number of jobs dependent on interprovincial trade. But using the most recent Statistics Canada data along with some fairly standard methods, I construct my own detailed estimates of employment linked to interprovincial trade between Alberta and Quebec and the rest of the country.

The numbers may surprise you.

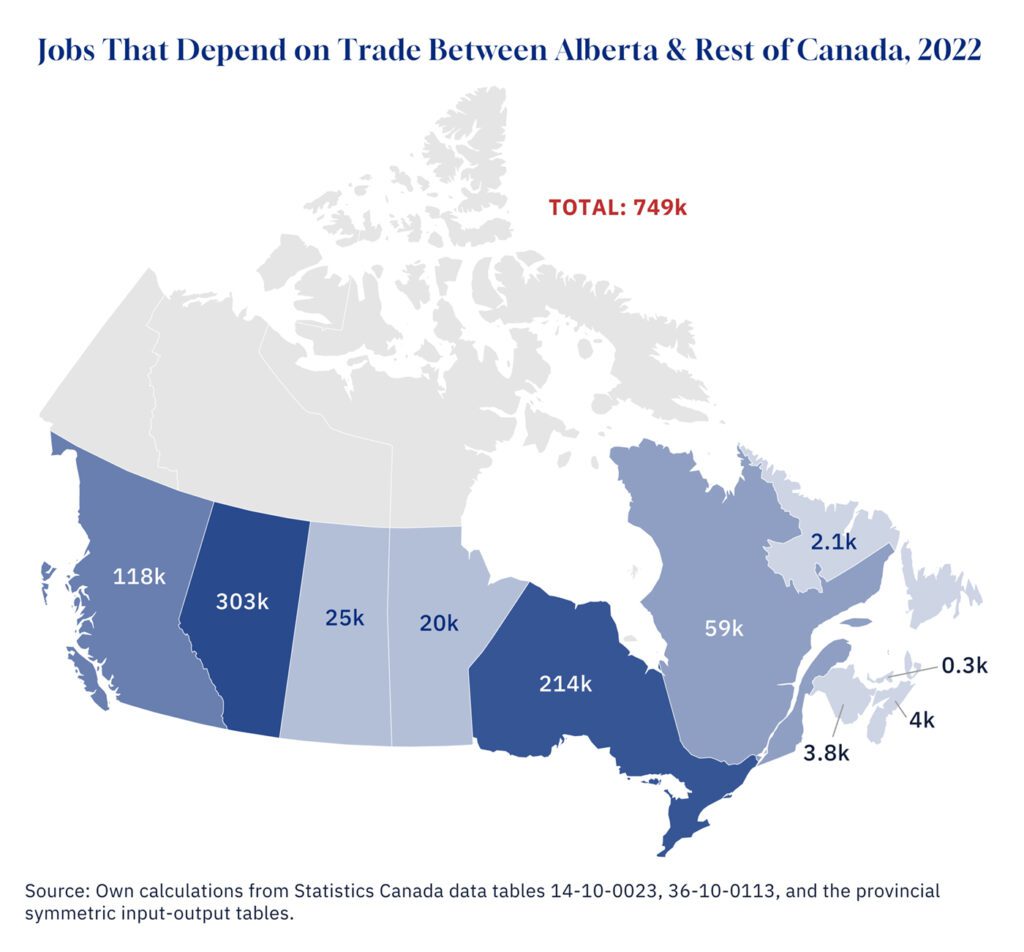

In Alberta, for 2022—the latest year for which this type of estimate is possible—I find that just over 300,000 jobs were dependent on exports to the rest of Canada. This includes not only those directly involved in producing exports but also jobs further up the supply chain: suppliers to exporters, and their suppliers, and so on. That’s about 14 percent of all jobs in the province. And this figure doesn’t even count those jobs at businesses that rely on imported inputs from outside the province.

Interestingly, that means more Alberta jobs depend on trade with the rest of Canada than depend on trade with the United States!

Not just Alberta’s problem

This interdependence flows both ways.

I estimate that Ontario has more than 200,000 jobs that depend on exports to Alberta. British Columbia has around 120,000, and Quebec roughly 60,000. Nationally, about 750,000 jobs in 2022 were dependent on interprovincial trade with Alberta alone. Given growth since then, a reasonable estimate for today likely exceeds 800,000 jobs.

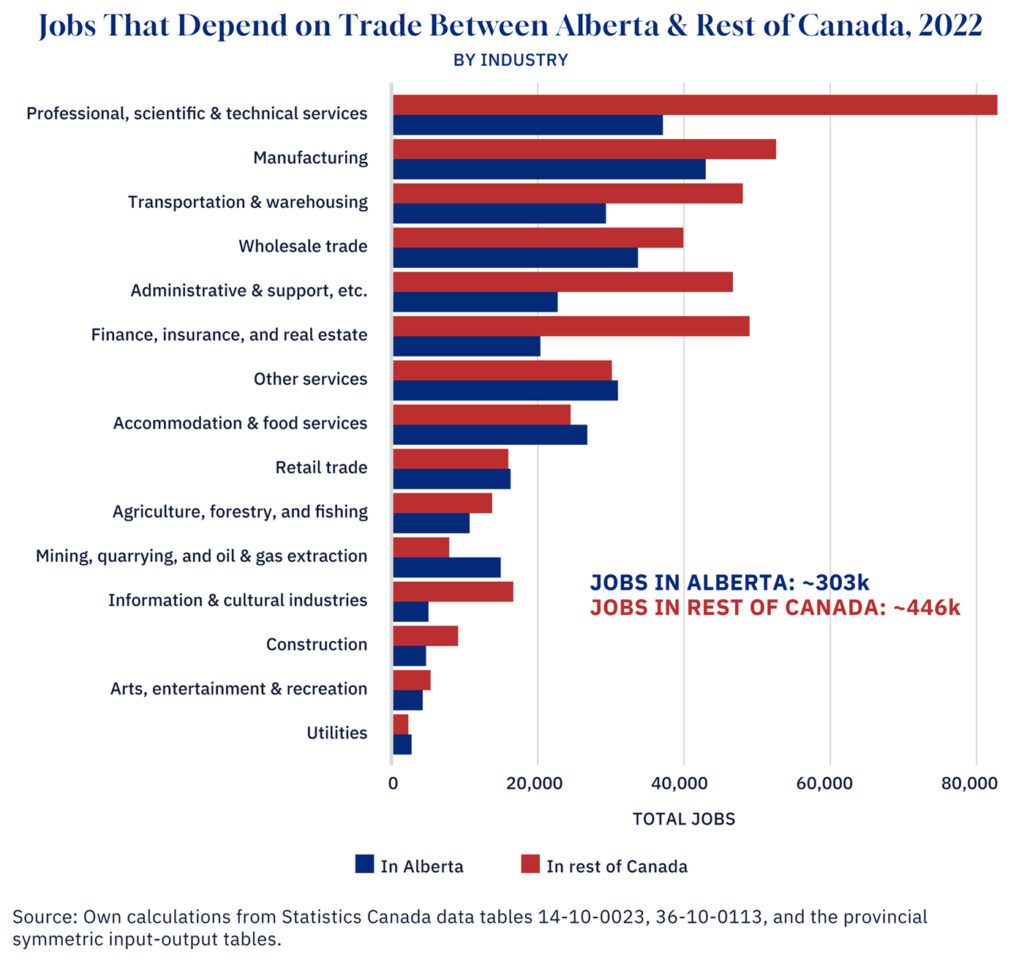

And these aren’t all oil and gas jobs. In Alberta, the largest exposure is in manufacturing (43,000 jobs), followed by professional and scientific services (37,000), wholesale trade (34,000), and transportation and warehousing (29,000). In the rest of the country, professional and scientific services are most exposed, with about 83,000 jobs dependent on exports to Alberta, followed by 53,000 in manufacturing.

Of course, separation wouldn’t necessarily mean all these jobs would disappear. But using the U.K.’s experience as a benchmark, a long-term loss of about 15 percent of trade volumes might be a reasonable place to start. Applied to the roughly 800,000 jobs that currently depend on trade to and from Alberta, that implies around 120,000 jobs nationally could be at risk.

Quebec separatism risks even more

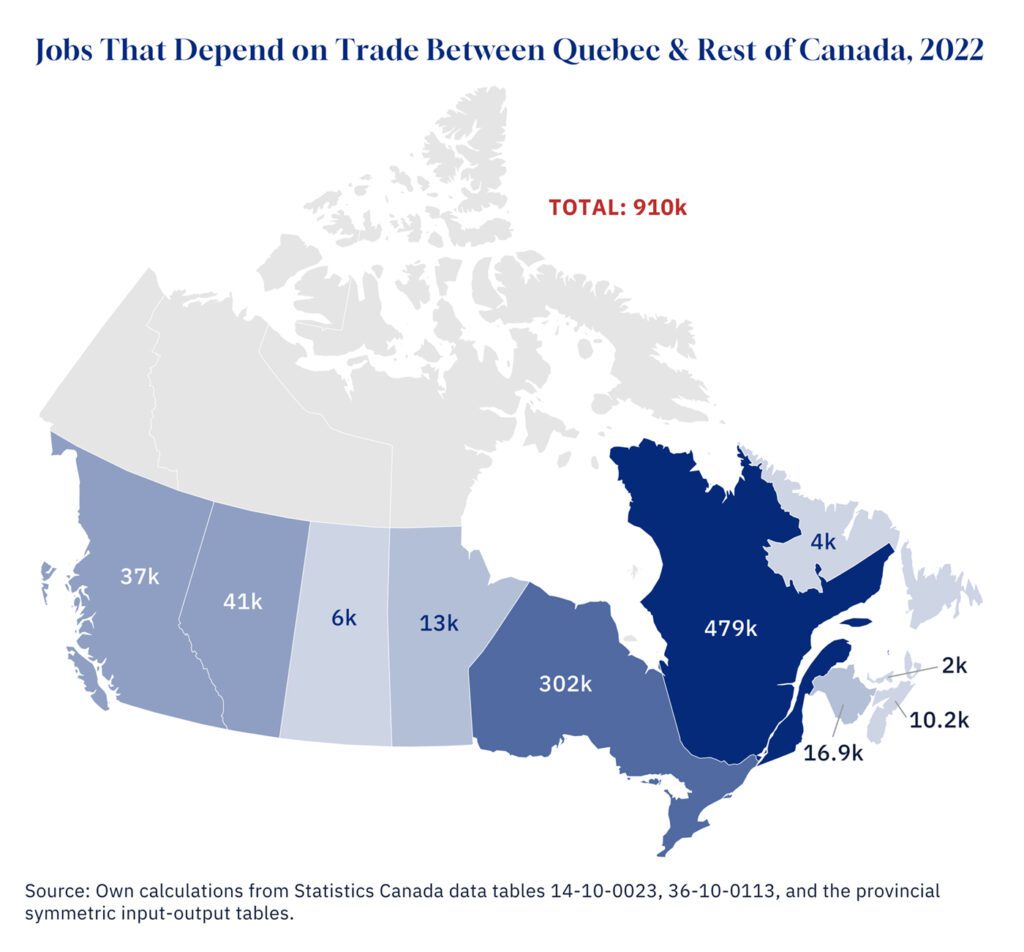

Quebec represents an even larger exposure.

If the Parti Québécois wins the provincial election later this year—as current polling suggests—a referendum on independence may follow. Roughly 500,000 jobs in Quebec depend on exports to the rest of Canada, and an additional 400,000 jobs elsewhere in the country are tied to trade with Quebec, most of them in Ontario.

Beyond jobs, the broader economic stakes are even more substantial.

Losses beyond jobs

I estimate that the total value of GDP tied to interprovincial trade between Alberta and the rest of Canada reached $140 billion in 2022. For Quebec, that figure was over $130 billion. Combined, that’s more than 10 percent of the entire Canadian economy. And this isn’t some measure of the value of trade, which is larger still. Instead, it’s a measure of the wages, salaries, corporate profits, and other sources of income generated by that trade.

If trade volumes were to fall by 15 percent, again just to illustrate a potential magnitude, that could result in GDP losses of roughly $40 billion and risk something on the order of 300,000 jobs—a serious short-term hit to an economy already struggling.

What’s at stake

All told, about 1.7 million jobs were dependent on interprovincial trade with Alberta and Quebec in 2022. Today, that number could easily approach 2 million.

The short-term risks from rising separatist movements in both provinces are very real. While the depth of this sentiment—especially in Alberta—may not be as significant as some polling suggests, governments at all levels would be wise to consider whether their policies or rhetoric are inadvertently fanning the flames.

Federally, that may mean reassessing regulatory and policy decisions that have slowed national economic growth or contributed to regional frustrations. Provincially, it may require reflecting on whether some actions are emboldening separatist voices.

Canada is a democracy, of course, and people are free to advocate for separation. But those pursuing or encouraging that path should weigh the economic trade-offs, which carry real consequences right across the country.

No matter the path forward, one thing is clear: the potential short-term economic costs of separation—lost jobs, lower incomes, and reduced GDP—should be taken seriously. Especially at a time when Canada’s economic strength—and its future prosperity—is anything but certain.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum.