It will be critical for Canada to double-down on its relationship with Japan as its most trusted partner in the Indo-Pacific, write Jonathan Berkshire Miller and Stephen Nagy.

It will be critical for Canada to double-down on its relationship with Japan as its most trusted partner in the Indo-Pacific, write Jonathan Berkshire Miller and Stephen Nagy.

By Jonathan Berkshire Miller and Stephen Nagy, September 24, 2020

The Japan-Canada partnership remains underdeveloped despite both countries sharing democratic institutions, the opportunities and challenges of having a close relationship with the United States, and an increasingly complicated relationship with China.

Some have compared the bilateral ties to an old marriage, one characterized by predictability and stability requiring few major changes. While this may have been true in the 1990s, today’s bilateral relationship is badly in need of an upgrade.

The Indo-Pacific region faces numerous systemic challenges to both countries. These include but are not exclusive to North Korea’s development of missiles and weapons of mass destruction, a revisionist China that is challenging its regional neighbors on land and in the maritime environment, and China’s signature Belt Road initiative, which aims to reconfigure the region’s integration away from an ASEAN centric one to one that gravitates outward from China based on Beijing’s rules.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also aggravated many of the developmental challenges for regional stakeholders having been blighted by the coronavirus-induced recession.

Washington’s unorthodox diplomacy under the administration of President Donald Trump has further complicated the geopolitical landscape, challenging both Japan and Canada to redefine their diplomacy to effectively address their shared and individual national interests.

Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, a staunch defender and promoter of a rules-based order, and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau began the process of upgrading the relationship so that it reflects the enormous changes both countries are experiencing in international affairs.

On the economic front, Japan — in the absence of U.S. leadership — took on the baton and pressed forward to support international free trade. Signature initiatives include the Comprehensive and Progress Agreement on Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP) — or the TPP-11 — which includes Canada.

The TPP-11 represents an important shift in Japan-Canada relations as both states, alongside the other nine members, are championing trade norms that will be critical toward protecting intellectual property rights, and enhancing both labor and environmental standards to provide a 21st century template for trade.

To further maximize the gains from this partnership, Japan and Canada should actively seek to advocate for an expansion of TPP members while, at the same time, carve out space for the U.S. to return to the trade pact. The United Kingdom, Thailand and even Taiwan are top candidates, although South Korea and other countries should be courted as well.

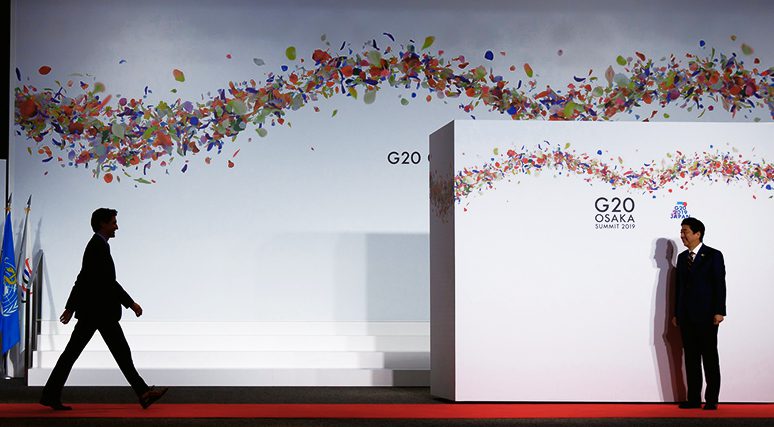

During Japan’s host year of the Group of 20 talks in 2019, Tokyo inked a crucial trade deal with the European Union and promoted the importance of quality infrastructure. These multilateral agreements align strongly with Canada’s longstanding commitment to multilateralism, international institutions and a rules-based approach to international affairs.

Upgrading the bilateral relationship should include infrastructure and connectivity projects in the Indo-Pacific, either through a bilateral mechanism between Tokyo and Ottawa or through a multilateral partnership with other middle powers and Japan.

On the security front, Japan-Canada relations remain fixed on developing overlapping foreign policy that is more nuanced and less security centered compared with the Trump administration. Neither Canada or Japan has any delusions about China’s core interests in the region and willingness to press for them as illustrated by the recent national security law in Hong Kong, repeated Chinese incursions around the Japan-controlled Senkaku Islands (also claimed by China, which calls them Diaoyu) in the East China Sea, island building in the South China Sea and violent clashes along the Indo-Chinese border.

Nonetheless, both Japan and Canada do not want their bilateral relationship with China to be security centric. As a result, Tokyo and Ottawa are creatively finding ways to realistically engage Beijing.

Examples include advocating for Japan’s “free and open Indo-Pacific” vision to keep the U.S. tethered to the region. Japan’s focus on infrastructure and connectivity and economic development became a more central feature of the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy. In fact, Canada and other middle powers have appreciated Japan’s less security focused approach to the region as it matches its capabilities, capacities and diplomacy in the region focused on development, but also buttressing a rules-based order.

Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga — who was a longtime Abe confidante — will likely maintain most of the main policies of his former boss. However, the new leader will need to set the tone for engagement both with the United States and China. This will be critically important no matter whether Trump or Democratic candidate Joe Biden will be in office in the U.S. after this November’s election. We already know who will be in office in China for an undetermined number of years.

So what is the trajectory for Canada-Japan relations under Suga?

Canada and Japan have long been key international partners, both bilaterally and multilaterally. The two countries are vibrant democracies that support open trade, investment and the rules-based international order. Their cooperation internationally spans a range of bodies including: the G7, G20, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, Asian Development Bank, International Monetary Fund, Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The two sides are also committed to enhancing trade relations with the CPTPP.

One common challenge for Ottawa and Tokyo is managing their most crucial — and sometimes mercurial — ally, the United States. A re-elected Trump will likely double-down on his “America first” unilateralism, further eroding the rules-based order that smaller countries like Canada and Japan depend on for security and stability. In this scenario, Japan will reach out proactively to other middle powers such as Canada to protect multilateral trade and buttress international institutions.

At the same time, expect Japan to work with other similar-sized powers to collectively lobby the United States.

Here, Canada will be a key partner of Japan in steering the United States in a more multilateralist direction — or in at least protecting each other’s interests as was seen in the past with former Canadian Ambassador to the U.S. Michael Wilson’s backdoor cooperation with Japan on trade issues. Wilson passed away in February of last year. The U.S.’s predictability will still be in question even if Joe Biden is elected, with Washington remaining blighted economically and in terms of health thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic and deepening social divisions across the country.

What does this mean for Canada and Japan? The urgency to enhance their partnership grows more by the day. Within Asia, an assertive and revisionist China is actively eroding the rules-based order in the region through economic coercion, hostage diplomacy and expansionist claims in the East and South China Seas. How the new Japanese leader deals with China should inform Canadian interactions with Beijing. Tokyo has suffered from both economic coercion and hostage diplomacy like Canada and there is much to learn from Tokyo as to how to diffuse these tensions as Abe adeptly did during his tenure. Focusing on “free” and “open” will necessarily be part of that approach.

It will be critical for Canada to double-down on its relationship with Japan as its most trusted partner in the Indo-Pacific. There is often a temptation for Canada and Japan to fall into the “comfortability trap” — a state where both countries have few irritants, plenty of cooperation but a lack of strategic purpose in their relationship. This status quo must end.

Canada and Japan both share concerns — albeit at different levels — on China’s increasingly aggressive moves in the region. The volatility in the region underpins the need for Japan to mobilize the diplomatic capital it has amassed under Abe’s tenure in order to push forward the rules-based liberal order. Suga should look to drive forward the expansive — but still relatively nascent — security network in the region made up of several U.S. allies and partners. Canada can play a role here also in the free and open Indo-Pacific vision to work together with Japan — and other like-minded partners in the region — to promote these shared interests.

Jonathan Berkshire Miller is a senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the Japan Institute of International Affairs. Stephen Nagy is a professor at the International Christian University in Japan and fellow with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute.