This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Richard Shimooka, March 14, 2024

The past several weeks have been a busy one on the topic of espionage in both Canada and the United States, from a retired United States Air Force colonel passing secrets on an online dating website to a foreign handler, to the sentencing of Jack Teixeira for leaking a trove of classified materials over Discord. Meanwhile here at home, the Winnipeg Microbiology Lab controversy has dominated headlines after revelations that two now-fired scientists at Canada’s most secure lab worked closely and covertly with the Chinese government for many years.

Of all these cases, this one is likely the most serious breach—not only due to the significant potential damage caused in the transfer of whatever knowledge and materials they had access to, but also because of what it says about Canada’s approach to national security in the current geopolitical situation.

Always expect espionage

It is important to note that espionage occurs on a daily basis in every country. It is impossible to stamp out. How it is managed, though, is the more critical question.

Take for example one of the most closely guarded programs ever put together: the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb during the Second World War. Despite concerted efforts, even that program was heavily penetrated by individuals spying for the Soviet Union, including at the Los Alamos site.

A key factor behind many of these individuals’ decision to aid the USSR was ideological support of communism. In the years after the 1917 Russian Revolution and the economic hardships visited by the Great Depression of the 1930s, communism drew many adherents from across American society, a number of whom would eventually join the Manhattan Project. Many justified their subterfuge along these ideological grounds, but there were other motivations as well. Some saw science as a universal public good that should not be held captive by one state or another, others believed that enabling the distribution of such technology to both the U.S. and the Soviet Union would constrain the weapons’ use by providing an appropriate balance of power.

As the Second World War ended and the Cold War began, the U.S. government and its allies placed greater urgency on curtailing espionage. Scientific advancement was seen as a key conceptual battleground for this emerging conflict. The potential for science to be adapted into a war-winning weapon was clear considering the immense destructive capability afforded by the atomic bomb, but it extended to all manner of areas. The famous kitchen debate between Vice President Nixon and Premier Khrushchev in 1958 two years after the launch of Sputnik may have been the most visible manifestation of the technological struggle.

A key feature of America’s scientific and technological ecosystems at this time was the establishment of several bodies to facilitate research and development. They included national labs like Los Alamos, Sandia, and Lawrence Livermore, as well as a number of other bodies like the National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research. The latter became a key funder of scientific endeavours within academia that were viewed as promising for national security and civilian uses.

The same occurred in Canada, which established the Defence Research Board (now known as Defence Research and Development Canada or DRDC), which was so important that its director was elevated to a deputy minister-level post, on par with the head of the armed forces.

A new age of great power conflict

That level of seriousness has not persisted here at home. Whether through complacency or incompetence, Canada has clearly lost its way in today’s emerging geo-strategic environment, where autocratic states, largely led by China and Russia, are aggressively seeking to assert their dominance. They sow division amongst Western democracies and undermine the existing rules-based order.

Somewhat unlike the Cold War, this era’s great power conflict is not heavily predicated on the balance of military forces. The calculus has changed. The situation in Ukraine not withstanding, in general, conflict is based on tenets outside of the battlefield: political and social stability and economics and prosperity. The former is evident in Russia and China’s malign influence in Western elections, most concretely here in Canada.

On the economic power and prosperity front, one of the key battlegrounds is scientific development and technological innovation. While it is arguably as—or even more—important than it was during the Cold War, its nature has completely changed. Development has become far more diffused across society; rather than solely being a government-led effort as it was from the 1940s to the 60s, it now involves a far wider array of technological sectors.

Witness the challenge between the U.S. and China over advanced computing, most acutely in AI. It resulted in America implementing restrictive policies for technology transfer and sales to China that could enable these systems.

This competition creates an immense challenge for governments on how best to foster technological development to outpace the heavy-handed state-backed model pursued by China. In many respects, the private sector ecosystem for innovation and development is one of the strengths of the democratic free market system in that private investment can be much more agile and effective at producing results while allowing governments to focus on investments in areas without immediate profitability but perhaps much greater long-term outcomes.

As we have seen, however, balancing the demands of keeping a free and open society with the need to maintain some level of information security is immensely challenging.

It is evidently difficult to demarcate a consistent and clear policy on acceptable versus illegal conduct. But not impossible. The U.S. government has tended to be extremely risk-averse, imposing fairly stringent regulations and procedures for work in their national laboratories, even to the detriment of some of their programs’ efficiency.

Foreign nationals, including permanent residents within the U.S., are highly restricted in the positions they can obtain. There are entire sections of lab campuses that are off-limits to non-nationals, and human reliability programs that undertake fairly deep counterintelligence-type background investigations are ubiquitous. In areas critical to national security scientific and technical inquiry, security is taken seriously.

Canada’s failures

All of this brings us back to the Winnipeg lab controversy. There are certainly more questions that have not been answered thus far, but the broad contours of the situation are now evident. Clearly, a significant portion of the work undertaken at the facility on infectious diseases represents among the highest levels of national security considerations for the country. Its operation is essential for ensuring public health not just in Canada but internationally, which necessitates the ability to communicate its work to a broader audience. At the same time, many of the materials worked on there are highly sensitive and must be safeguarded for their potential security risk.

This dynamic creates immense complexity compared to other technology sectors where there is no such direct link to the public’s well-being, thus ensuring security is more straightforward. But this only calls for even greater oversight and clearly articulated policies to govern actions at the laboratory. Yet that was not the case. The level of security concern seems lackadaisical at best, completely at odds with the highly sensitive work undertaken at the facility. Health Minister Holland admitted as much when he stated that the staff were able to avoid suspicion due to an “inadequate understanding of the threat of foreign interference” and “lax adherence to security protocols.” Some of the reported justifications for this particular approach have parallels with the Los Alamos scientists who conducted espionage for the USSR on the atomic bomb project.

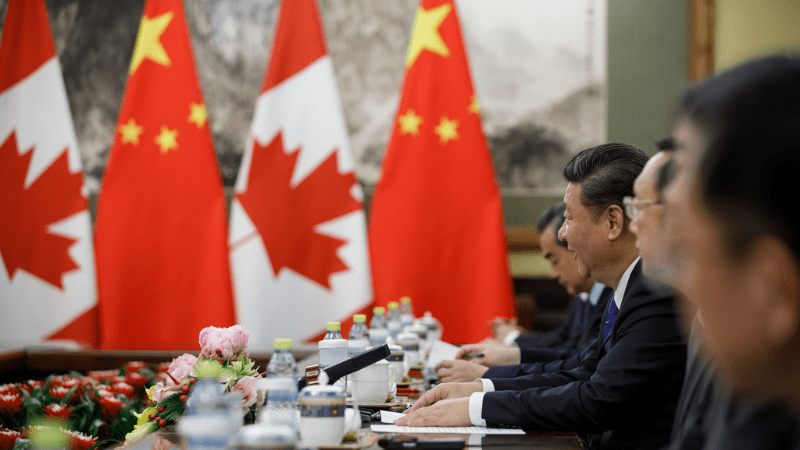

The government, however, has not operated as if they have gotten the message. For instance, despite the two scientists being escorted from the Winnipeg lab in 2019 (and subsequently fired in 2021) as a result of the alleged covert actions on behalf of the CCP, the government still decided to partner with the Chinese government on the ill-fated CanSino vaccine deal in 2020. It is the cherry on top example of the baffling disregard for the seriousness of the threat.

The bottom line is that the infiltration of the Winnipeg lab is completely unacceptable, as is the apparent absence of comprehensive oversight of the project from government or security services.

As highlighted, all Western democracies deal with espionage and data breaches regularly; in isolation, this controversy should provide valuable lessons for how to manage and prevent such instances. The larger problem is what it reveals about the systemic nature of Canada’s clearly inadequate broader security regime.

Overall, the situation is bleak and this incident will have serious repercussions, particularly as it will even further erode the trust of our allies. Our partners will simply raise further barriers in their dealings with Canada in this and other areas over potential security issues—and understandably so.

Exacerbating everything has been the political leadership’s effort to hide the allegation for over two years, followed by the complete refusal to admit any wrongdoing. The unwillingness to fully acknowledge and own the situation will delay the security reforms desperately needed to address the breach and prevent such incidents from occurring again. Doing so would undercut the government’s overall argument that it did nothing wrong.

Regardless, the situation requires immediate redress. This incident is indicative of precisely the type of concern being raised by other national security communities within the government of Canada as well as Canada’s closest allies. Responding with myopia only serves the narrow political interests of those in power. The lasting consequences are to the immense detriment of the country’s security and reputation.

Richard Shimooka is a Hub contributing writer and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute who writes on defence policy.