The government has shown a troubling predisposition to deficits and spending, writes Sean Speer. We need a renewed focus on what principles should govern federal fiscal policy.

The government has shown a troubling predisposition to deficits and spending, writes Sean Speer. We need a renewed focus on what principles should govern federal fiscal policy.

By Sean Speer, Nov, 7, 2017

There’s been plenty of debate about the Trudeau government’s budget-making since it was first elected in October 2015. Two recent developments – the Fall Economic Statement and news that Ottawa will reprofile further infrastructure spending into the future – provide some useful insights into its fiscal policy. Investigating these two separate yet linked government announcements can help us come away with a better understanding of what’s behind Ottawa’s deficit and where it may be heading in the medium- and long-term.

The real story here seems increasingly clear. This isn’t about economic theory, stimulus-like investments, or short-term fiscal improvements. This is basically a case of run-of-the-mill spending growing faster than revenues. And the underlying evidence suggests it may get worse rather than better.

Much of the reporting on the Fall Economic Statement was about how the deficit has shrunk. This is true. A combination of improved economic conditions and delays in spending have caused deficit projections to go from $28.5 billion to $19.9 billion this year and shrink cumulatively by nearly $25 billion in the subsequent four years. But this belies a deeper dive into federal fiscal policy.

Ottawa’s fiscal policy is increasingly unmoored from any consideration of the business cycle. It’s notable, for instance, that the idea that deficit spending is justified due to the economic circumstances has mostly disappeared from the government’s talking points. We no longer hear about “kick-starting” the economy as we did in the campaign. Now it’s all about long-term investments to “build the Canada of tomorrow,” as the minister of finance has put it.

The circumstances may be different. The message may have changed. But the answer is still the same: more spending.

This ought to concern even those who were nonplussed by the government’s choice to run deliberate budget deficits. Or its decision to abandon its three-year timeline to restore budgetary balance. Or its judgement to put off setting out a medium-term plan to eliminate its deficit.

There are few voices out there that believe the government should run deficits in good and bad times. Even fewer are in favour of deficit spending as an end. These are positions that should be able to secure a broad cross-section of support across the intellectual and political support.

But not with the Trudeau government. The Fall Economic Statement both boasted about Canada’s strong economic performance and signaled that the timing is wrong to focus on budgetary balance. It’s hard to understand under what circumstances a deficit wouldn’t be justified according to this perspective.

This deficit-for-deficit’s sake mentality is the main reason we’ve gone from $30 billion in accumulated deficits, as the Liberals promised in the campaign, to now projecting nearly $75 billion over their four-year mandate. A drop in revenues is only a small part of the story as others have demonstrated.

What’s interesting is not just Ottawa’s predisposition to deficits and spending but also its spending composition. Remember the message during the election campaign and through its first two years (including for example Minister Morneau’s 2017 budget speech) was that infrastructure was a major or even principal source of the government’s incremental spending and in turn its budgetary deficit.

The evidence is clear that this claim is overstated. I’ve previously written about how incremental infrastructure funding only represents a quarter of the Ottawa’s ramped-up spending. A recent announcement that the government is “reprofiling” (which basically involves moving it into subsequent years) billions of infrastructure dollars reinforces this point. This means that infrastructure funds earmarked in 2016-17 and 2017-18 will be redirected to the future and thus can’t be attributed to the present year’s deficit. Put simply: Short-term spending hikes and the budget deficit weren’t driven by infrastructure funding.

I should be clear that this isn’t a criticism about failing to expedite infrastructure projects or a call for Ottawa to accelerate infrastructure spending. It’s typical for some infrastructure funding to be reprofiled. We’ve also written elsewhere in favour of focusing on long-term projects with high economic return. The point is it’s wrong to assume that major, new infrastructure spending is behind the federal deficit.

At least for now. There is a risk that it contributes to higher deficits in the medium- and long-term. This is something that we’ve been warning about since ahead of last year’s budget. Let me explain.

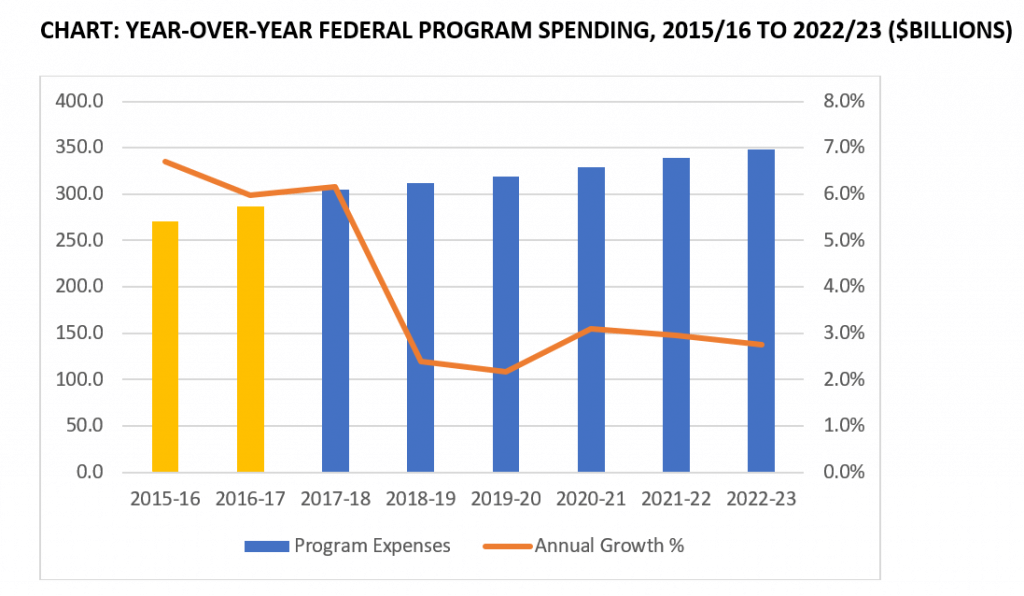

Annual program spending has grown by an average of 6.1 percent in the first two years of the Trudeau government. The Fall Economic Statement projects that it will fall to an average of 2.3 percent in the final two years. This isn’t a best-case scenario that eliminates the deficit. This is the government’s own plan (see chart below). Even after more than halving year-over-year spending growth the government would still be running deficits exceeding $10 billion per year.

One can’t help but be skeptical that Ottawa will achieve such a drop in spending growth for a host of reasons, including:

- Reprofiling of infrastructure funding into later years will cause spending to be higher-than-projected in those years.

- Likelihood of new spending priorities (e.g., Fall Economic Statement’s enhancements to the Canada Child Benefit and Working Income Tax Benefit) will also drive spending – particularly as we approach the 2019 election.

- Unlikelihood that the government will cut or slow spending based on past record and proximity to 2019 election.

There’s a good probability then that average spending growth will amount to something closer to 6.1 percent than 2.3 percent. The result would be to put considerable pressure on the budget deficit.

One example: Program spending is projected to grow by 2.4 percent from $304.9 billion to $312.2 billion between this year and next. If it were to grow by 6 percent instead, it would go from $304.9 billion to $323.2 billion and ceteris paribus the deficit would go from $18.6 billion to $29.8 billion.

The outcome would potentially be a longer and higher deficit than is currently projected. The real story then is not that the deficit is shrinking but rather that the medium-term risk is more to the downside than to the upside.

This isn’t a crisis. I agree with those who caution against alarmism. Federal public finances are strong. Higher deficits in the medium-term aren’t going to change that.

But surely we shouldn’t succumb to complacency either – especially since (1) Ottawa’s deficit is principally about discretionary spending rather than infrastructure-related stimulus, and (2) the focus on short-term fiscal improvements neglects the medium-term risks to the government’s projections. These insights should catalyze a renewed focus on what principles should govern federal fiscal policy. This is the conversation we ought to be having. This is the best way to ensure that federal public finances remain strong.

Sean Speer is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.