This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Shawn Whatley, February 13, 2024

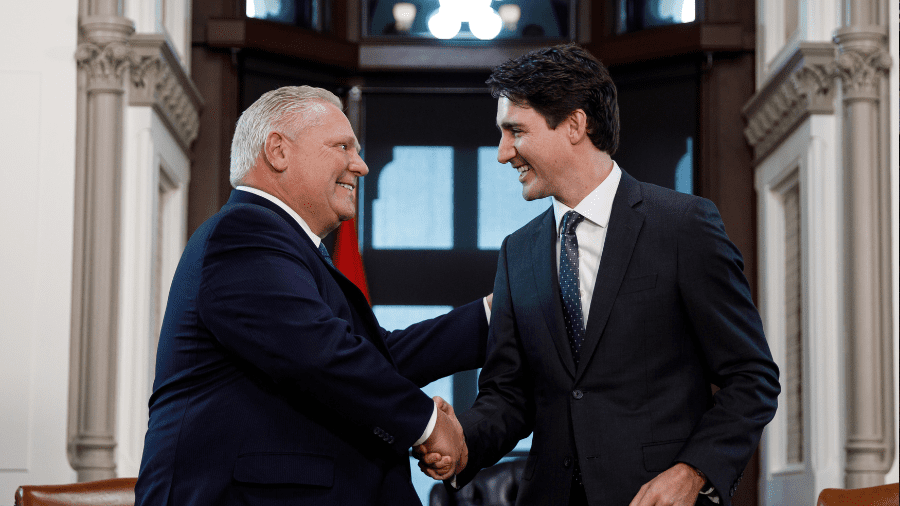

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Ontario Premier Doug Ford congratulated each other last week on signing a $3.1-billion, three-year health-care agreement, ending two years of haggling.

In December 2022, Trudeau had said there’s “no point putting more money into a broken system.” But by February 2023, Trudeau had forgotten his point and signed a $196.1-billion deal with the provinces. It included side deals with individual provinces to be worked out later, which we saw in Ontario last week.

Trudeau is not the only one who changed his mind. Throughout 2022, the provinces fought for a $28-billion increase in transfer payments, with no strings attached. But they settled for $17 billion, with strings to be sorted out later.

Premier Ford seems pleased that his side deal trimmed Trudeau’s strings down to a three-point plan, centred on primary care and data sharing. Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos had initially demanded five broad and more substantive deliverables.

In a statement, Trudeau’s office said that, “Universal public health-care is a core part of what it means to be Canadian. It is the idea that no matter where you live or what you earn, you will always be able to get the care you need.”

Notice the language here: an “idea” is not a promise or a guarantee. Actual delivery of care is not part of the deal.

Maybe that’s unfair. Perhaps the three-point, strings-attached plan is in fact a promise.

The first string forces an increase in new primary care teams throughout the province. Family Health Teams (FHTs) offer a basket of bonus services patients would otherwise have to pay for themselves. Physicians in FHTs get a small army of helpers funded by government. Is it any wonder everyone loves them?

The second string promises 700 new spots in medical education. If the new physicians are fully trained in Canada, they would need to split the 700 spots between undergraduate and postgraduate training, potentially creating 350 more doctors per year.

Canada has always poached many of its physicians from other countries: one in four physicians have historically been foreign trained. So it’s a nice gesture to try to train more of our own doctors.

However, the gesture will take between 11 and 15 years to help the 2.3-million Ontarians who don’t have a family doctor. Family doctors need four years of medical school, plus two to three years of residency. Even if all the new doctors open a full-time, 1,500-patient family practice, it will take 11 years to close the gap.

But many family doctors carry far fewer patients, and the 350 new spots would probably split between specialists and family docs. A more realistic estimate would generate 175 new family doctors a year, who each care for 1,100 patients. That would create a 15-year wait to meet current needs.

But it gets worse. Many medical students avoid family practice at all costs. In 2023, 100 family practice training positions in Ontario went unfilled. Opening spots in a program that students avoid seems absurd.

In family practice, computers and paperwork have replaced patient care. Family doctors spend 19 hours on paperwork each week. To make matters worse, primary care usually gets hit hard when it comes time for governments to cut fees and funding.

Economic uncertainty is no way to foster growth. To stay sane, most family doctors limit office practice and pursue palliative care, hospitalist medicine, emergency medicine and other areas of focused practice.

The final string includes a promise to upgrade the digital infrastructure in hospitals, capture more data and share it with the federal government. This sounds nice, but the challenge has always been the cost of data collection, and how to determine what to measure. Not everything we measure matters, and not everything that matters can be measured.

Ontario is the fifth province to reach an agreement, after British Columbia, Alberta, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Each province seems pleased, even with relatively small agreements — like bulls being led by small rings through the nose.

Writing about the fall of communism in 1990, Robert L. Heilbroner, an economist, best-selling author and lifelong socialist, noted that the “system deteriorated to a point far beyond the worst crisis ever experienced by capitalism; the villain in this deterioration was the central planning system.”

The latest federal-provincial agreement represents more central planning designed to fix problems created by central planning. Maybe it’s time to try something new?

Shawn Whatley is a physician, Munk senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and author of “When Politics Comes Before Patients: Why and How Canadian Medicare is Failing.”