This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, November 21, 2023

The relationship between the U.S. and China has been marked by cooperation, competition and a deepening rivalry.

This reflects the complex dynamics between the world’s two largest economies and the asymmetries that still exist between the status-quo power, the U.S., and the rising power, China.

Harvard Scholar Graham Allison described the dynamics of the interaction between a rising power and a status-quo power in his book “Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?” His intention was explicit, the U.S. and China can and should avoid the so-called Thucydides Trap, a situation in international relations where an up-and-coming power challenges a dominant power, leading to the potential for conflict.

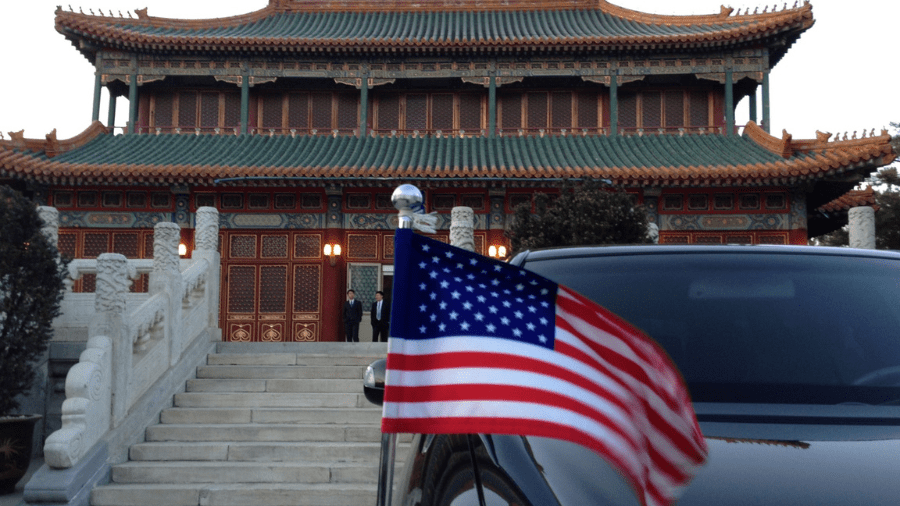

Recent efforts to reset the U.S.-China relationship, such as the summit between U.S. President Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, on Wednesday prior to the APEC Summit in San Francisco are laudable, but in reality their relationship faces significant hurdles due to structural challenges.

How Washington and Beijing navigate their strategic competition will affect the national interests of Japan, Canada and Southeast Asia among other nations.

One of the primary structural challenges in U.S.-China relations lies in their economic interdependence, which simultaneously fuels cooperation and competition. The two nations are deeply entwined in trade and investment, making it difficult to decouple their economies without substantial disruptions to their financial well-being.

Notwithstanding the benefits of this trade relationship, this interdependence has also led to intense competition, particularly in areas such as technology, intellectual property rights and market access.

Concrete examples of behavior hindering a reset can be observed on both sides. The U.S. has raised concerns about China’s unfair trade practices, including intellectual property theft and forced technology transfers. Additionally, China’s state-led economic model, characterized by subsidies and market distortions, has raised concerns about a level playing field for American companies.

Kevin Rudd, Australia’s former prime minister and now ambassador to the U.S., echoed these concerns with his observation that the Chinese economic management under Xi is turning to the Marxist-Leninist left with the state assuming more control of the economy and people’s lives.

On the other hand, China has perceived U.S. actions, such as export controls and restrictions on Chinese investment, as attempts to contain its rise. Moreover, the U.S. ban on Chinese technology companies such as Huawei and restrictions on Chinese students and scholars have further strained the relationship. These actions contribute to a lack of trust and impede efforts to reset the U.S.-China relationship.

Beyond economic factors, geopolitical competition poses another structural challenge to this consequential relationship. The U.S. and China have different core interests in various regions, resulting in strategic competition for influence. This is exemplified by Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea, where China’s territorial claims and assertive behavior have raised concerns among neighboring countries and the U.S. Its actions in the Taiwan Strait are also a cause of concern as it refuses to renounce the use of force in its quest to unify with Taiwan.

Resetting the U.S.-China relationship will take sustained diplomacy and concrete action on both sides.

First, while military-to-military communication is necessary to provide clarity on each side’s thinking, capabilities and their respective approaches to crises, Biden and Xi need to reengage on economic and security dialogue at three levels: the leaders level, at the working group level and through back-channel dialogue among scholars from both countries, as well as third countries like Japan.

The absence of economic and security dialogue at all three levels has led to misunderstandings and strategic dissonance, increasing the chances of a conflict breaking out.

Resuming mutual visits by scholars and students and ensuring they are safe from “hostage diplomacy” and won’t be detained so as to be used as political bargaining chips is also a must. Frankly, this will be a tall order in the China context with the adoption of ambiguous domestic security policies and laws that have made previously acceptable research and academic exchanges potential state security infractions to be used by the government to attack and silence its perceived political enemies.

Second, ensuring Taiwan’s security is in international communities interest. Taiwan should be the centerpiece of the two side’s confidence building measures. The U.S. should reiterate its commitment to the “One China” policy and support for a mutually acceptable time frame for peaceful unification between Taiwan and the mainland. This should be done in concert with strong commitments to enhance Taiwan’s deterrence against any military action by Beijing. China, for its part, needs to reciprocate by renouncing the use of force in seeking unification.

Third, Beijing has voiced the view that cooperation with the Washington cannot proceed in an environment where China is being pressed by the U.S. on issued related to technology, the South China Sea, Taiwan or other matters. Both countries need to identify four to five concrete areas of cooperation that would be protected from politics.

The environment, transnational disease prevention, denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, student exchanges and even commitments to join infrastructure and connectivity projects in third countries — as former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe once negotiated with President Xi during a 2019 summit in Beijing — should also be on the table.

Both sides should realize without sustained, visible and meaningful joint cooperation, bilateral relations become overly focused on the security differences within the relationship.

Washington and Beijing cannot do this alone and nor should they. Nations from Japan, to Canada, to Southeast Asia, Europe and others all have a stake in the success or failure of U.S.-China relations. They don’t want the strategic competition between the two to force them to choose a side. They can contribute to stabilizing and fostering a more constructive U.S.- China relationship through coordinated diplomacy, crafting opportunities for the U.S. and China to come together for more dialogue.

The upcoming 2024 U.S. presidential election will complicate sustained diplomatic engagement between the U.S. and China. Biden will be painted a China “fanboy” by his Republican opponent dependent on the diplomatic deals he reaches with Chinese leaders from now until Americans go to the polls to pick their next leader. Xi in contrast may see merit in pausing cooperation until the result of the U.S. election is determined, hoping that a less experienced and systematic President Donald Trump returns to the White House.

Such positions may be politically convenient but would contribute to long-term instability and magnify the chances for accidental or intentional conflict between the two great powers. Leaders in both countries need to recognize that neither country is going away and that a long-term commitment to meaningful economic and security dialogue, multilevel exchanges and cooperation must be the foundation for an awkward but needed peaceful coexistence.

Dr. Stephen Nagy is a professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute; a senior fellow at the MacDonald Laurier Institute; and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.