Allies cannot take U.S. support for granted. American presidents have long complained about the lack of allied burden-sharing, but such complaints have merit and, under Mr. Trump, a new sense of political urgency, write Joel Sokolsky and Christian Leuprecht.

Allies cannot take U.S. support for granted. American presidents have long complained about the lack of allied burden-sharing, but such complaints have merit and, under Mr. Trump, a new sense of political urgency, write Joel Sokolsky and Christian Leuprecht.

By Joel Sokolsky and Christian Leuprecht, April 4, 2019

When representatives of the original 12 members of NATO stepped forward to sign the North Atlantic Treaty 70 years ago, the U.S. Marine Band played two selections from George Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess: It Ain’t Necessarily So and I Got Plenty o’ Nothin’. Then-U. S. secretary of state, the legendary Dean Acheson, would later observe in his memoirs, Present at the Creation, that the choice of music “added a note of unexpected realism.” Until the end of the Cold War, the alliance could never quite shake the suspicion that behind the burgeoning bureaucracy, the elaborate military command structure and the carefully crafted nuclear and conventional strategies, all was not necessarily so, and that in a real crisis NATO would be found to have plenty of nothing. These concerns seemed well-founded as the alliance coped with a never-ending series of internal divisions, dilemmas and seemingly insoluble contradictions about how it dealt with the threat from the East while holding itself together.

But survive it did, because “flexible response” was not simply the official name given to the strategy adopted in 1967 – it was how the alliance approached seemingly intractable and inherently contradictory problems of a strategic and, above all, political nature. True to the messy nature of democratic government itself, this collection of (mostly) democracies managed to surprise and confound its critics by adopting a series of initiatives that placed political compromise above military and strategic orthodoxy and intellectual rigour. The end result was that the allies stayed allied and, in doing so, achieved ultimate victory in the Cold War.

In the post-Cold War and post 9/11 eras that followed, this flexibility would be both vindicated and challenged anew as NATO enlarged to the east and undertook new missions in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and Libya. With the most recent return of a Russian threat, the alliance has engaged in significant deployments and assistance in the Baltic states and Poland. As it does so, however, its prospects for survival again look uncertain. The U.S. Trump administration has raised serious doubts about the future of the American commitment, that indispensable bulwark and glue that has made the alliance work since 1949. Has NATO’s renowned flexibility been stretched beyond its limits?

As with Mark Twain’s obituary, reports of the alliance’s imminent demise due to weakening U.S. support may be “greatly exaggerated.” The 2018 U.S. National Defense Strategy focused on the threat that Russia and China pose to American interests and reaffirmed that “Mutually beneficial alliances and partnerships are crucial to our strategy, providing a durable, asymmetric strategic advantage that no competitor or rival can match. … Every day, our allies and partners join us in defending freedom, deterring war, and maintaining the rules which underwrite a free and open international order.” The U.S. defence budget for the 2018/2019 fiscal year included more funding to support American forces in Europe as the U.S. presides over large allied exercises, deployments and military assistance on NATO’s eastern flank as part of operation REASSURANCE, including the multinational enhanced Forward Presence (eFP). Summed up by Barry Posen, a professor of political science at MIT: “The U.S. military commitment to NATO remains strong, and the allies are adding just enough new money to their own defence plans to placate the President. In other words, it’s business as usual.” Keeping the “Russians out, the Americans in and the Germans down,” is, after all, how Lord Ismay, the alliance’s first secretary-general, summed up the purpose of NATO.

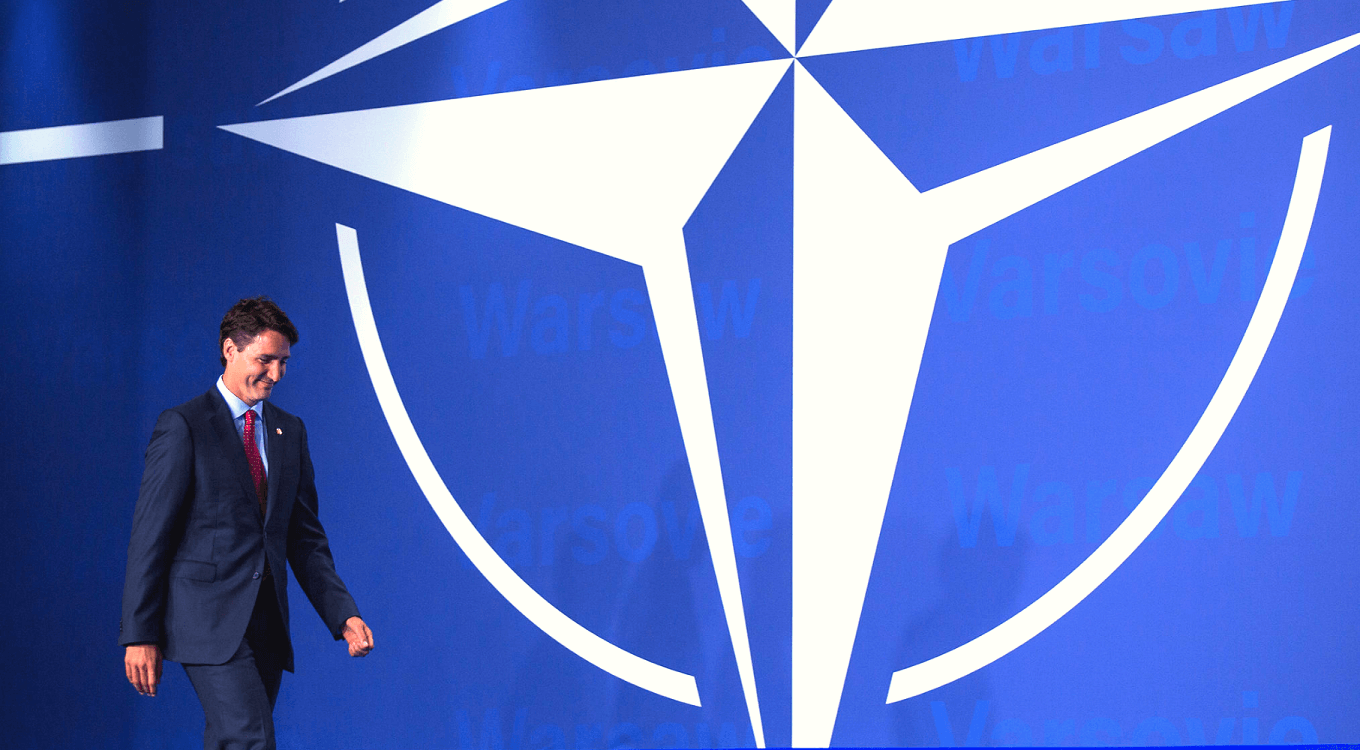

Lord Ismay’s point was as poignant then as it is now: Allies cannot take U.S. support for granted. American presidents have long complained about the lack of allied burden-sharing, but such complaints have merit and, under Mr. Trump, a new sense of political urgency. Among members of Congress, the foreign-policy elite and the American public, support for the alliance remains strong. At the same time, the consensus is that America’s allies in NATO have the collective military and economic capacity to increase their individual military expenditures and contribute more to allied initiatives. Although Canada is not augmenting defence spending significantly, it appears to have recognized the gravity of the Russian threat and Mr. Trump’s warnings: Canada just renewed its leadership role and major contribution to NATO’s eFP in Latvia as well as NATO’s training mission in Iraq through 2022.

For an alliance where good politics has always been as important as good strategy, this remarkable 70th anniversary is a propitious moment for the allies to take note of that old flexibility and resolve by responding positively and concretely to U.S. concerns. Nothing less than the survival of NATO is at stake.

Joel Sokolsky is a professor at the Royal Military College and a senior adviser with the strategic studies program of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Christian Leuprecht is Eisenhower Fellow at the NATO Defence College and Class of 1965 Professor in Leadership at the Royal Military College, cross-appointed to Queen’s University and Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.