This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Melissa Mbarki, August 19, 2022

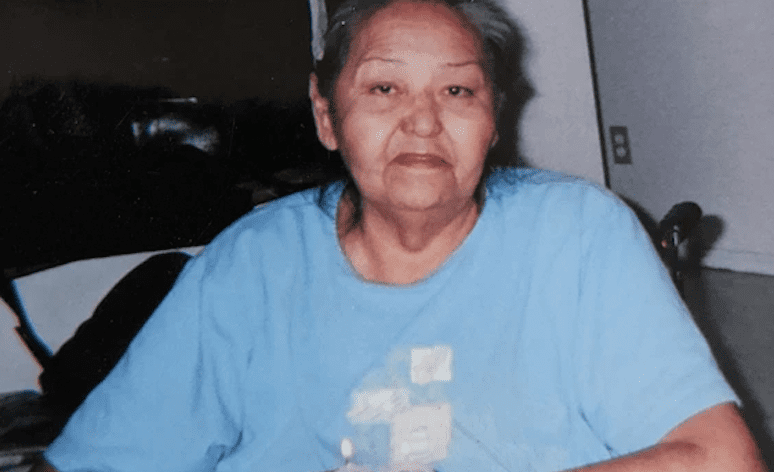

In 1943 my grandmother was forcibly taken from her home at the age of five. She returned to her community when she was 19.

One of the saddest things she ever told me was that upon her return, she didn’t know her family. She didn’t recognize her brothers and sisters and she barely recognized her mother. She didn’t know who she was, and that scared her.

Such was the experience of many of the approximately 150,000 First Nation children who were taken from their homes and placed in residential schools by the Canadian government over a period that lasted more than century. Children were abused in those schools; children died at alarming rates. All of this has been well-established by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as well as by survivors’ testimony from decades of court hearings.

So it was very frustrating to learn last week that the federal government continues to try to evade responsibility for what Pope Francis has deemed a genocide.

According to The Canadian Press, which obtained documents through the Access to Information Act, an admission of federal guilt was edited out of a speech written for Carolyn Bennett, then minister of Crown-Indigenous relations, in the days following the announcement by the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc Nation that what are believed to be the unmarked graves of about 200 children had been detected on the site of the former Kamloops residential school.

A draft version of the speech said children at the residential schools “experienced unthinkable trauma, including physical, mental and sexual abuse at the hands of the federal government by simply attending school.”

However a later version of the speech, which was ultimately never delivered, omitted the key words “at the hands of the federal government.”

The facts regarding residential schools and the federal government’s role are indisputable.

Canada’s first residential school opened in Brantford, Ont., on Jan. 1, 1831. The Mohawk Institute was operated by the Anglican church. Fifty-three years later, amendments to the Indian Act provided for the creation of a residential school system, funded and operated by the Government of Canada and Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian and United churches.

On April 1, 1920, residential schools were made mandatory by the federal government for every First Nation child between the ages of seven and 16. This policy was also applied to Métis and Inuit children, not just to children with Indian status under the Indian Act.

The abuse and neglect at the residential schools had been reported to the government as early as 1907, when Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce, chief medical officer for the Department of the Interior and Indian Affairs, reported a mortality rate as high as 25 per cent for enrolled children. By Jan. 1, 1930, more than 80 such institutions were in operation across Canada.

On Sept. 4, 1951, another amendment to the Indian Act gave provincial governments jurisdiction over child welfare on reserves. This became known as the “Sixties scoop.” Thousands of Status, Métis and Inuit children were “scooped” from their homes and adopted, predominantly by non-Indigenous families, or sent to residential schools.

On Jan. 1, 1969, the authority for the operation of residential schools was transferred to the federal government. The government could have changed our history by closing the schools. It didn’t. Rather, it decided to keep them open for many more years. It allowed the abuse to continue. The last federally operated residential school did not close until Jan. 1, 1996.

I quote these dates and timeline, available for viewing on the Canadian Encyclopedia, because the federal government was involved with residential schools from the time they were opened until the day they closed. Federal politicians and bureaucrats wrote and implemented assimilation measures for Indigenous children and used the Indian Act to enforce such measures.

In 2008, then prime minister Stephen Harper apologized for the government’s historic failure to protect Indigenous children and acknowledged the consequences of residential schools on future generations.

What we have now seen is the Liberal government trying to cover up something that has already been proven beyond a doubt. It’s just another kick to the survivors and their families who are still struggling today from the abuse and neglect they endured while attending a residential school.

Melissa Mbarki is a policy analyst and outreach co-ordinator at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a member of the Treaty 4 nation in Saskatchewan.