This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, January 9, 2025

This has been an eventful year—and we are barely one week into 2025. You’d be forgiven if you forgot about Alberta’s efforts over the past year to gain public support for leaving the Canada Pension Plan.

So let’s refresh our memories and go back to 2019 when Alberta formed the “Fair Deal Panel” to investigate ways to enhance its autonomy within the Canadian federation. Among the panel’s recommendations (put forward the following year) was for the province to investigate creating its own provincial pension plan.

Unlike federal programs such as equalization, pensions fall under an area where provinces have the unilateral authority to act. So Alberta could choose to withdraw from the Canada Pension Plan, and in doing so, the panel argued, reduce its subsidies to the rest of the country.

But while it’s true any province can leave the CPP unilaterally, the terms of such a withdrawal are not something the province alone can dictate.

The most critical issue of all in such a move is how much of the CPP’s massive investment fund the province would receive. Last fall, the Government of Alberta claimed it was entitled to more than half of all assets—a figure prominently featured in the APP engagement process.

Many, including myself, took issue with this claim. And in response, the federal chief actuary was asked to provide their own interpretation of what the CPP Act had to say.

We now have their conclusion in a clear and accessible report. It’s worth a read.

In short, Alberta’s claim was rejected. But despite this, the potential for a separate provincial plan remains. I’ll explain.

Competing interpretations

Let’s start with the two key interpretations that have emerged regarding how Alberta’s share of CPP assets should be calculated:

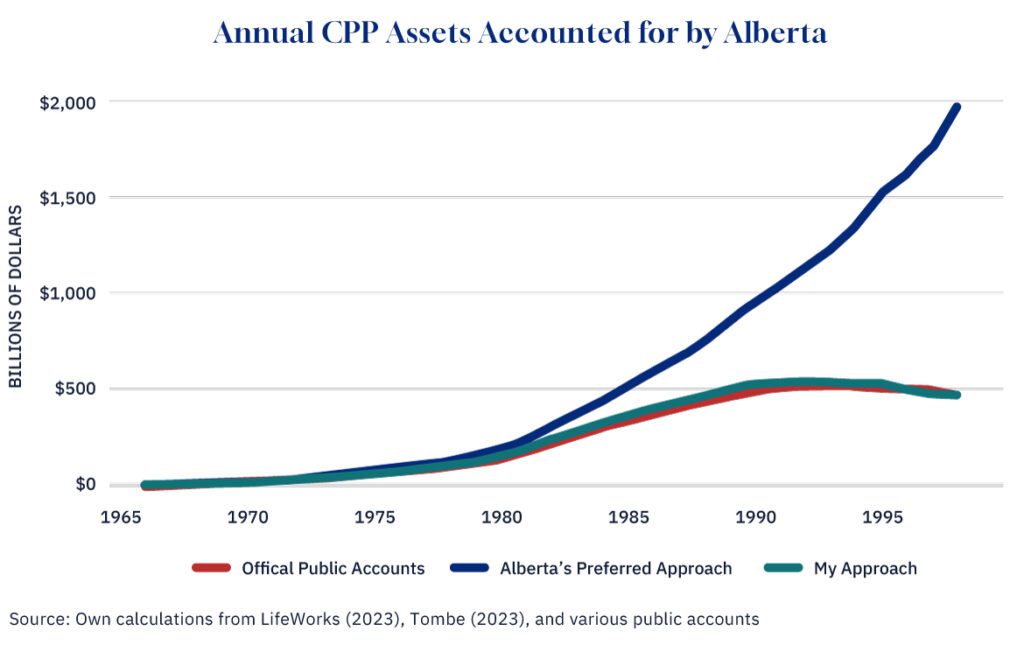

1. The Government of Alberta’s view (via LifeWorks): Their preferred estimates reversed the clock and hypothetically isolated Alberta’s contributions and expenditures, with all surplus allocated to a stand-alone account. Under this interpretation, they calculated that Alberta would be entitled to 53 percent of CPP assets—around $334 billion.

2. My own interpretation, published shortly after the government’s: I argued that the act’s language was relatively clear and implied a different method: splitting CPP investment returns based on each province’s historical share of total contributions. This method aligns with the CPP’s historical practice and treats all contributions equally, regardless of where they originated or where benefits were paid. This results in a much smaller 20–25 percent of CPP assets going to Alberta.

I was motivated mainly by how the CPP actually operates, a plain reading of the act itself, and how we recorded in the public accounts the amounts accounted for by each province for decades. My interpretation closely matches the first thirty years of the CPP, while Alberta’s preferred approach is way off the mark. (We stopped tracking this officially in 1998.)

Pretty cut and dry, but not everyone agreed. And determining which interpretation to use is critical. They differ by over $200 billion today, which obviously has significant implications for any potential future of the APP.

Enter a neutral third party: the chief actuary of Canada.

The chief actuary’s view

The chief actuary’s analysis mainly rests on three core principles:

1. Actual CPP returns are split, not hypothetical ones. The analysis does not attempt to reverse the clock or simulate a hypothetical APP, as Alberta’s government would prefer. Instead, it focuses on the actual returns earned by the CPP investment fund.

2. Returns must be split into positive shares for all provinces. Investment returns are shared among contributors, with no province “owning” a disproportionate share beyond their contributions.

3. Only contributions matter. Benefits paid to Albertans shouldn’t factor into the calculation, as the legislation is clear that the split depends only on contributions.

Each of these principles deviates from what the Alberta government would prefer.

The result? CPP returns should be split in proportion to the share of total CPP contributions accounted for by a province’s employees/employers. For Alberta, that’s just over 16 percent of the total, and therefore the province would receive 16 percent of the total CPP returns.

Show me the money!

Alberta was disappointed by the lack of a specific number.

“It did not contain a number or even a formula for calculating a number,” complained the finance minister’s press secretary. He’s mistaken. The report contained a precise formula that can easily be applied to the publicly available data to get a number. (See Table 1 of their report for the formula.)

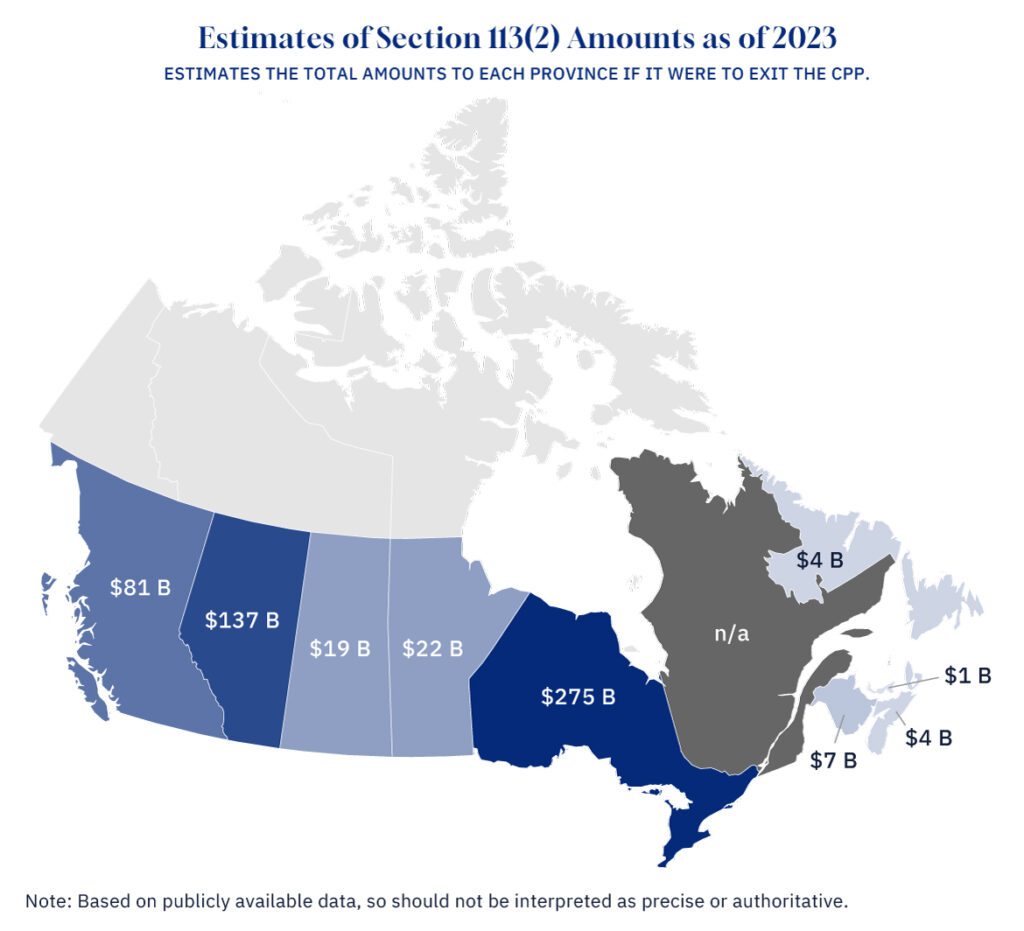

Indeed, it’s incredibly simple to apply the formula for all provinces. So I do that below using data through 2023. Alberta: $137 billion. Ontario: $275 billion. And so on. You could do it using a pocket calculator. There’s nothing fancy involved.

Of course, these numbers change every day. We invest in stocks, bonds, and a wide variety of other assets whose value fluctuates with global markets. And the publicly available data has certain limitations. But the formula is a crystal clear and unambiguous rejection of the government’s approach.

What this means for an APP

It’s not the end of the line. The chief actuary is an authoritative voice, but not definitive. If the Government of Alberta truly disagrees with this interpretation of the act, then they can launch a reference case through the courts. (I strongly believe that this would not result in a different outcome, but it’s an option nonetheless.)

A reduced share of CPP assets also doesn’t mean Alberta couldn’t establish its own pension plan. It does, however, alter the financial calculus.

My estimates suggest a contribution rate between 8.2 percent and 8.6 percent would suffice, depending on the level of surplus or “buffer” Alberta chooses to maintain. That’s lower than the current base CPP’s 9.9 percent rate, but higher than the 5.9 percent rate touted by the Government of Alberta.

The chief actuary’s analysis provides much-needed clarity and hopefully will lead to a more informed policy debate.

There are real benefits to a separate pension plan, including potential cost savings from lower contribution rates. Such benefits come with significant risks and trade-offs. A separate provincial plan would be subject to potential political interference, adverse demographic developments, greater exposure to investment volatility, and more.

Balancing these benefits and costs/risks is where the real challenge lies—and where reasonable people may disagree.

The size of the benefits is now far smaller than what the government was trying to convince Albertans of for the past year. If they couldn’t win the debate with $334 billion in the window, imagine the challenge with less than half that amount.