This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, September 17, 2025

With widespread job losses and rising unemployment, it already feels like a recession for many Canadians.

Earlier this month, Statistics Canada reported that employment fell by 66,000 jobs in August. That headline caught attention—and rightly so—but it’s important not to overreact to any single month of data. Labour force surveys can be volatile and subject to revision.

What matters more is the broader trend. But, unfortunately, that looks even worse. And Canadians are feeling it.

According to recent research from Abacus Data, two in three people are worried about their ability to afford basic necessities. And nearly half are worried about the upcoming year.

Google search interest in “recession” has been elevated since 2022. Not since the financial crisis have Canadians searched for the term so consistently for so long. And at least some research suggests these search trends potentially align with actual downturns.

But whether we’re officially in a recession is a harder question. Even former Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz hedged, saying we may be “sliding in the direction” of one. That uncertainty reflects the fact that recessions are difficult to call in real time. I’ll explain why that is, what economists watch for, and what Canada’s latest data is telling us now.

Why forecasts fail

The most widely used definition, from the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research, describes a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.”

It’s a deep, broad, and persistent economic contraction.

That’s a helpful way to look back and classify past downturns, but it requires a wide range of data—on GDP, jobs, incomes, production, and more—each of which comes in slowly, is often revised, and rarely points in the same direction all at once. That’s what makes recession forecasting so difficult. Even when one is already underway, we often don’t realize it until many months later.

One study of GDP forecasts across dozens of countries since the 1990s found that nearly two-thirds of predicted recessions didn’t happen. Worse still, of the recessions that did happen, over 95 percent weren’t predicted the year before. Even during a year when a recession was already underway, more than one in five forecasts still expected no downturn at all.

So while we can’t say for sure what’s coming, we can look closely at what’s happening now.

A weakening job market

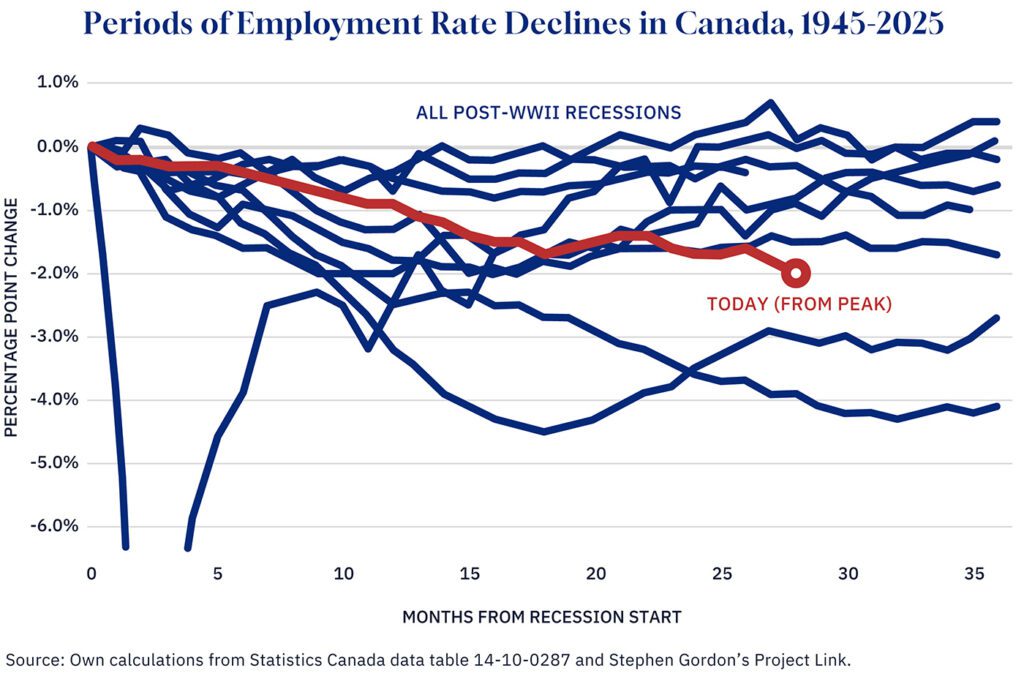

Let’s start with the labour market. Since early 2023, the national employment rate has dropped by two full percentage points. That’s a bigger decline than we saw in nearly every Canadian recession in recent decades—except for 1981, 1990, and during the COVID crisis. And this isn’t just due to population aging and an increasing number of retirees. The employment rate among those of prime working age (25 to 54 years) is down even more.

The unemployment rate has also increased by two points—equivalent to roughly half a million more unemployed Canadian workers. And, again, this exceeds where many other recessions have been over the same period. It also triggers the so-called “Sahm Rule,” which signals a recession when the three-month average unemployment rate rises by 0.5 percentage points or more above its recent low. Canada crossed that threshold back in October 2023.

This is not due to a sudden wave of layoffs. Rather, it’s that finding a job has become harder. Businesses are posting far fewer vacancies, which has hit young people especially hard. Employment among those under 25 has dropped by roughly six percentage points since early 2023. Nearly half a million former students are now unemployed—up nearly 20 percent in just one year. That group alone accounts for half of the overall increase in unemployment.

Broad job losses

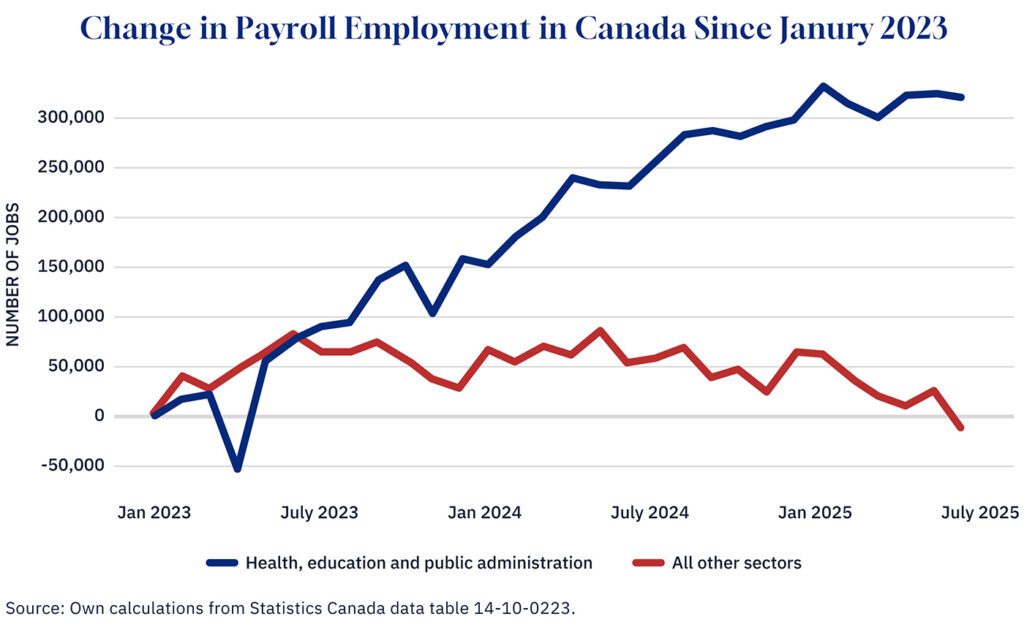

This slowdown is broad across sectors. Of the roughly 230 industries tracked through payroll data, 55 percent are now shrinking at once—something we usually only see in recessions. And the current 55/45 split between contracting and expanding sectors is worse than at any point since 2001, aside from the global financial crisis and COVID-19. And in 2008, this level of contraction didn’t show up until after the recession had already begun.

Even among sectors that are growing, the gains are narrowly concentrated. Over the past two and a half years, all net job growth has come from health care, education, and public administration. These sectors have added over 300,000 jobs. But outside of them, jobs are down 75,000 this year alone.

These labour market trends are mirrored in the broader economy.

A shrinking economy

Real GDP shrank in the second quarter this year. And labour productivity fell more than it had in any other quarter for several years.

Looking ahead, the latest forecast from BDLNow—a fantastic new real-time tool produced by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce’s Business Data Lab—projected last week just 0.3 percent annualized growth in Q3. That’s a sharp drop from the 2.3 percent forecast made back in July, leaving us on a knife’s edge today. But then it bounced back earlier this week to a projection of 1.5 percent growth.

Things are highly uncertain. But a little more weakness, and we may see two consecutive quarters of negative growth—something many would take as confirmation of a recession.

Of course, that “two quarters” definition is only a rule of thumb—and not always a reliable one. The United States saw a recession in 2001 without two negative quarters. In 2022, it had two quarters of decline without a recession being declared. Canada had a similar episode in 2015. In each case, there was enough strength elsewhere to argue against calling it a recession.

But that doesn’t seem to be the case today. Two-thirds of the more than four dozen monthly economic indicators I track regularly have deteriorated over the past year. We’ve seen a worsening trade, business confidence, manufacturing orders, EI claims, and more. Over the past quarter-century, only the financial crisis and COVID-19 saw more indicators flashing red.

So where does that leave us?

Whether Canada is in a recession or not remains unclear. If it is in one, I suspect we’ll mark its beginning as earlier this year. But if this isn’t one, it may be one of Canada’s most widespread and difficult slowdowns in decades—something that, for most households, feels little different.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum.