This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By J.L. Granatstein, April 20, 2022

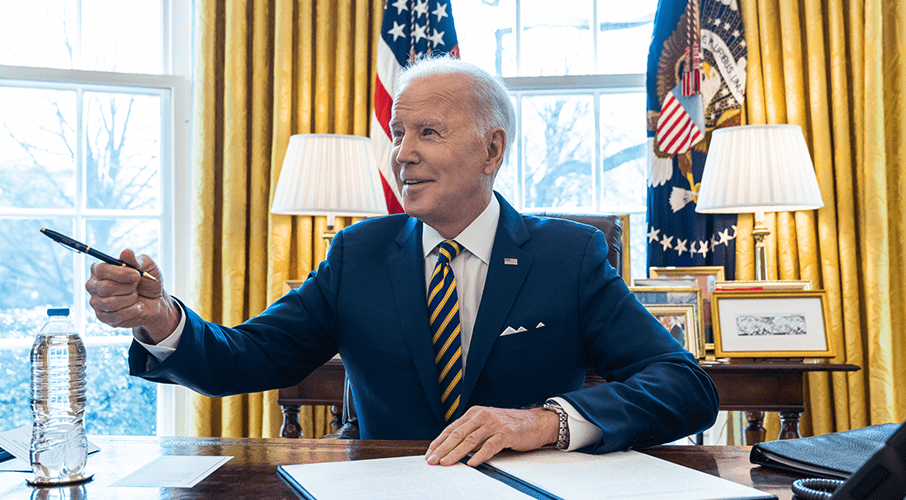

Joe Biden’s bumbling presidency has not been a great success thus far, with the botched withdrawal from Afghanistan, rising inflation, COVID-19, social unrest, and a sharply divided nation and Congress. But Biden’s response to the War in Ukraine has been a different story.

Indeed, the U.S. efforts to help Ukraine and deter Russia began months before President Putin ordered his troops to attack. As early as October 2021, U.S. intelligence agencies had reached the conclusion that Russia was preparing to invade Ukraine, and the European allies were so informed. At the beginning of November, that information was leaked to leading U.S. media and went public.

Soon, the Administration was releasing details on Russian troop numbers and movements and showing satellite photographs of the army’s equipment being positioned near Ukraine and for what Moscow claimed were joint exercises with Belarus. But the Russians were bringing in blood supplies, the U.S. then revealed—not something needed for exercises. In January 2022 the Americans said Putin was planning “false flag” operations to paint Ukraine as an aggressor that intended to heavily attack pro-Russian separatists in the Donbas. That was followed by further revelations that Russia planned a swift strike on Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital, with the intent of killing or capturing President Volodymyr Zelenskiyy and installing a puppet government. Biden then said that the invasion would occur on February 16. That turned out to be incorrect by 8 days: the invasion came in the early morning of February 24.

Moscow for years had been winning the disinformation wars against the West, and U.S. intelligence failures—the claims of Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq, for example—had helped weaken American credibility. But now, the accuracy of U.S. intelligence pointed to a robust spy network in Russia, almost certainly including sources in the Kremlin. Some highly placed officials, presumably opposed to the assault on Ukraine, must have passed on information. At the same time, government and commercial satellites tracked Russian troop movements while recent advances in cryptology and electronic interception, as well as the growing global reliance on computer networks and mobile communications, reinforced the amount of hard information the U.S. intelligence experts had.

Washington, in effect, was now employing transparency to counter Moscow’s propaganda and clumsy fabrications. Making such information public was completely unprecedented for the U.S. So too was Washington’s decision to share the intelligence it gathered with Kyiv, presumably in detail. (Curiously, perhaps, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy tried to downplay American warnings of an imminent invasion for fear of creating a panic and hurting Ukraine’s economy.) NATO allies and the “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance, both of which include Canada, were also shown the most secret intelligence reports. Some of the Europeans thought the U.S. might be warmongering, but events proved that Washington had it right. At the end of March, the head of French military intelligence was sacked, apparently because he had downplayed the possibility of Putin actually invading.

What is abundantly clear is that Washington’s tactics in going public with its intelligence, complemented by similar British efforts, had worked to weld the West together and, after the invasion, to spur increases in defence spending, most notably in Germany, and new interest in Finland and Sweden in joining NATO. The widespread condemnation of Russia for its aggression, the swift agreement on strong sanctions, and the continuing efforts to tighten them were a product of the Biden Administration’s intelligence revelations. “The intelligence community usually doesn’t like to share information; they want to hold it close,” Senator Mark Warner, the chair of the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee, said. But “What they’ve done is push the Russian timeline back. They’ve also, I think, allowed us to build this coalition that is virtually unprecedented.”

It is similarly obvious that Putin’s blatant lies about Nazis running Ukraine and genocide in the Donbas had failed to get public traction outside Russia. As Biden said shortly after the invasion, “We shared declassified evidence about Russia’s plans and false pretext[s] so that there could be no confusion or cover-up about what Putin’s doing. Putin is the aggressor. Putin chose this war. And now he and his country will bear the consequences.” The President, by sensibly refusing to implement a no-fly zone over Ukraine, also averted confrontations with Russian aircraft that might spark a wider war. After February 24 Putin’s unprovoked aggression was in plain view, and the United Nations General Assembly on March 2 voted 141 to 5 with 35 abstentions that Russia withdraw its troops at once. The UN is a weak reed and Putin paid no attention, but as an expression of global opinion, the vote was revealing.

And if American intelligence was correct, Putin’s was not. He, his generals, and his spies had anticipated a short campaign where Russian troops would be greeted as liberators. Putin could not have realized that his army with its vaunted reputation would prove so ineffective in anything but medieval-style sieges on urban areas and civilians. Putin also completely underestimated Joe Biden and the United States, and he failed to see Zelenskyy as the effective leader, communicator, and hero he became.

Biden and his Administration got it right, Putin blew it, and the Russian people are paying in full for his gross miscalculations. Let us hope Putin does too.

J.L. Granatstein is the former director and CEO of the Canadian War Museum and the author of Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace (3rd edition, 2021).