The true litmus case for the rules-based order will be its ability to evolve and withstand the challenges in the Indo-Pacific in the coming years, writes J. Berkshire Miller.

The true litmus case for the rules-based order will be its ability to evolve and withstand the challenges in the Indo-Pacific in the coming years, writes J. Berkshire Miller.

By J. Berkshire Miller, December 11, 2019

In early December, former senior officials, as well as A-list experts and scholars converged in Tokyo to discuss the fate of the international order at the inaugural Tokyo Global Dialogue, hosted by the Japan Institute of International Affairs (JIIA). The topic: “Is it possible to build an international order based on free, fair and transparent rules?”

Certainly, the rules-based liberal international order is under assault on a number of fronts: the rise of protectionism and widespread authoritarianism, growing skepticism about liberal values and the malfunctioning of international institutions.

As outlined by several speakers at the conference, including former U.S. deputy national security advisor Avril Haines and Bill Emmott, chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, these concerns are symptoms, rather than a cause of the current stress on the international system.

In the developed economies, there has been a widening gap of income disparity and disenfranchisement from citizens who are not benefitting from the financial successes of globalization. This has led to the growth of populist rhetoric around the world.

These economic tensions have been compounded by geopolitical challenge, with growing strategic rivalries and the marginalization of international law. These divisions are aggravated by the intentional misuse of digital tools — such as social media or cyber tools being used for misinformation campaigns.

Advances in digital technologies have radically made the world more convenient, from state administration and industry to individual lifestyles, and they have already reached an irreversible level.

The flip side is that technology is also empowering authoritarian countries, through cyberattacks, fake news, interference in the elections of other countries, and national surveillance and data hoarding by authoritarian states have been adversely affecting the international order. During the dialogue, participants insisted that the only way forward was for the international community to construct common rules compatible with advances in digital technologies.

Moreover, the international order is facing challenges from the changing security environment with a host of territorial disputes, growing strategic rivalries and development of cutting-edge military technologies.

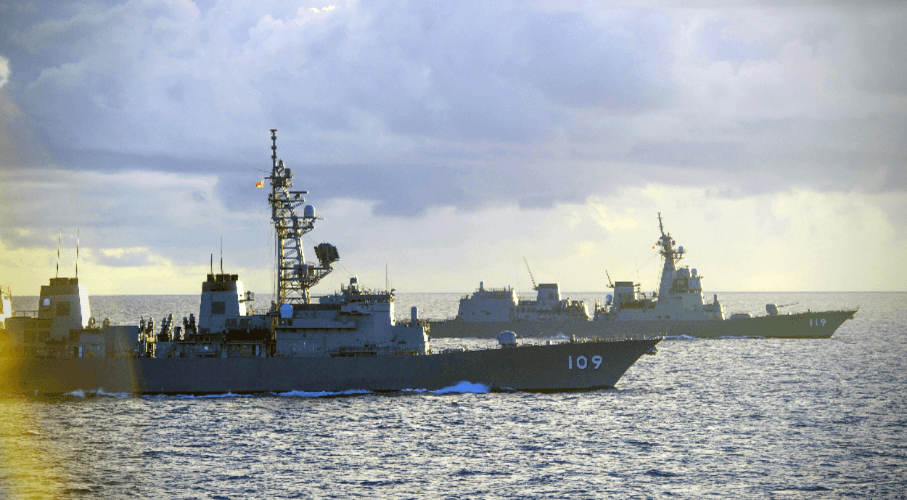

The Indo-Pacific region, in particular, is facing a host of shared security challenges, from maritime piracy and crime to heated territorial disputes. In this vast maritime space — stretching from East Africa to the Pacific Island chains — the foundations of commerce and security are secured through the freedom of navigation and secure sea lanes. The region relies on secure supply chain connectivity and sustainable development, that is done in transparent and equitable way.

Chief among the concerns in the Indo-Pacific region is the U.S.-China strategic rivalry.

As fear of a new cold war brews, however, the silver lining is that the basis of the next international order is gradually emerging in the form of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy. The Indo-Pacific concept has been gaining more currency by actors in the region, with United States declaring a FOIP strategy, in addition to other regional approaches by India and Australia.

But leading this charge has been the Japan, under the stewardship of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who has focused intense diplomatic efforts at framing the importance of the Indo-Pacific region — which Tokyo identifies as ranging from East Africa to Western North America. This is the geographic region that Japan looks to focus its FOIP vision to, among other areas, help promote sustainable infrastructure, protect and uphold free sea lines of communication and improve connectivity.

For Japan, the FOIP is core to its vision for the region going forward.

Yet, while the FOIP’s intellectual origins may lie largely with the Abe administration, the concept is non-exclusive to Japan, and the norms and laws that guide it are applicable to most countries in the region. In a sense, the Indo-Pacific region will not only emerge as the world’s stage for economic development and strategic competition, but will also be a test-case for the adaptability and evolutionary growth of the rules-based order more broadly.

Indeed, FOIP’s principles are meant to reaffirm, not transform, the rules-based international order. How is this playing out in the region? There is great economic opportunity in the region with large economies and diverse fast-paced growth in many middle-size economies. That said, alongside this economic growth is a large demand for infrastructure development in the region — some estimate the need for more than $4 trillion over the next 20 years.

To fill this void, several regional powers — including Japan — have the ability to work with states in the region for a sustainable way forward based on fair-lending, transparent institutions and long-term growth.

Yet, there are a number of key challenges to the rules and order in the region that have underpinned security and prosperity for the littoral states. In the South China Sea, Beijing continues to undercut international law and aims to subjugate its neighbors through extensive land reclamation, the imposition of military equipment and infrastructure, and the diplomatic splitting of states in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Meanwhile, Beijing also continues to raise regional concerns through its constant incursions into the maritime and airspace surrounding Japan’s Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

Japan remains a key component to promoting stability in the region through an inclusive FOIP. Indeed, the evolution of the FOIP is Japan’s active “opening of the tent” as it promotes the vision. Tokyo has been promoting the FOIP as inclusive and not aimed at any one state — clearly with a message to China that, believable or not, the FOIP should not be seen in adversarial terms.

In support of this opening, Japan has extended beyond the traditional focus on the U.S., Australia and India (who are members of a tepidly reborn quadrilateral dialogue that was dormant for 10 years) and has welcomed and pushed for greater involvement in the Indo-Pacific from states in Europe, such as the United Kingdom and France. Tokyo has also stressed the importance of this to other Group of Seven partners, such as Canada, that share similar norms, values and approaches to the rule of law.

Of course, the threats to the rules-based order are not limited to China. There continues to a rise of authoritarian governments — as on display in Russia, Turkey, Venezuela and elsewhere — that favor unilateral force and eschew the frameworks and utility of international institutions. The West, meanwhile, has also contributed to its own deterioration, through its lack of ability to resolve societal inequities and bridge the divide among its electorates. This has led to a rise in populist governments that promote nationalistic agendas ahead of multilateralism.

Despite this, however, the true litmus case for the rules-based order will be its ability to evolve and withstand the challenges in the Indo-Pacific in the coming years. Whether it is the rise of nuclear proliferation (in the case of North Korea) or the defiance of international laws and norms (in the case of China), this region’s future will guide the future prospects for the current rules-based system.

J. Berkshire Miller is deputy director and senior fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute. He is also a senior fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, the Asian Forum Japan (AFJ) and a distinguished fellow at the Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada.