This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Richard Shimooka, June 29, 2023

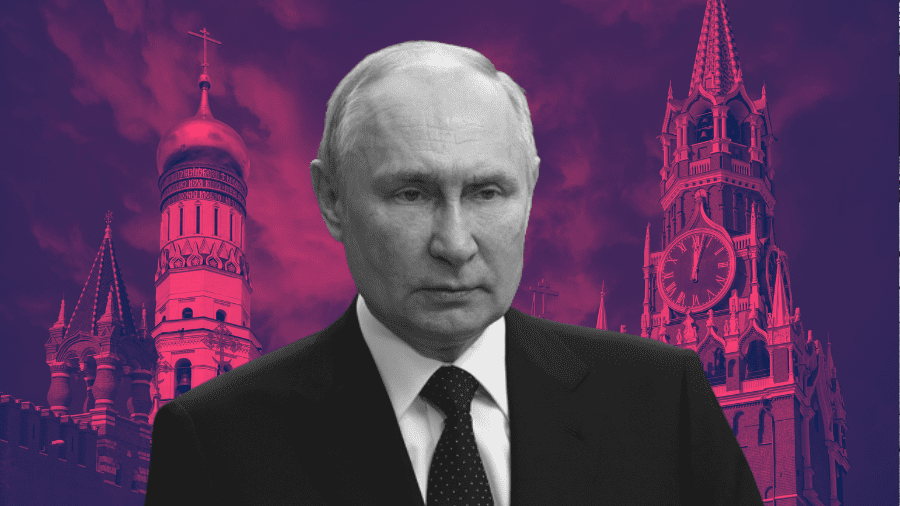

The short life of the Yevgeny Prigozhin-led Wagner mutiny within Russia over the past week has engendered significant attention and speculation by outside observers, despite the fluid situation. Claims of the regime’s instability and even imminent collapse abound. These analyses might be premature and hyperbolic, especially if one employs a longer view of Vladimir Putin’s regime. The best lens to understand the past few days remains court politics, also colloquially known as “Kremlinology.”

Over the past two decades Putin has constructed a system of governance that effectively cements his rule at the top. For all of his failings, most notably a badly conceived and heinous war inflicted on Ukraine, it is his crowning achievement: the system is robust and effective in keeping him in power.

While Putin has transformed the entire society to cement his position, the changes are particularly apparent in the system of governance at the top. It is designed to minimize the possibility of any challenge again his rule and to mitigate any damage when it occurs. A key hallmark is unclear and diffuse power relationships, where nobody feels at all comfortable in their position.

Different individuals derive different sources of power. Oligarchs, for example, control business and wealth across Russia, which enables them to wield immense influence on the economy. However, they have little political power and can be easily removed, either through quasi-legal or illegal approaches, such as corruption charges or assassinations.

Military leaders like Sergei Shoigu, Russia’s minister of defence, and Valery Gerasimov, chief of the general staff, draw upon a deeper well of institutional power. They represent the armed forces, which have a central, established role in the state. Militaries tend to be the strongest source of opposition in authoritarian regimes. Putin’s system of governance addresses this challenge by keeping the institution politically weak.

One aspect that emerged over the past few days is that the rank-and-file military likely despises the senior leadership, which Prigozhin publicized for his own benefit. This suits the needs of Putin, as they are weak puppets who are unable to effectively challenge his rule. Given the choice between poor battlefield performance and political control, Putin seems much more comfortable selecting the latter anyways.

The Wagner group can be seen as a further hedge against a military coup as it’s a private military force that exists independent of the military, just in case some of its elements turn against Putin. Yet it too is just as disposable. For example, Prigozhin ran the Internet Research Agency, a private company that was heavily engaged in foreign influence and intelligence operations. When its role in the 2016 election interference campaign was revealed, Putin disavowed any knowledge of the group, calling it a private company that operated independently of his government. In the same vein, Putin sought to distance himself from Wagner, especially over the weekend when the mutiny unfolded.

Ultimately, everybody serves at the behest of the new Czar and is in a constant effort to maintain their position of power, largely by ingratiating themselves with Putin. Signs of Prigozhin’s fall from grace have been apparent over the past months. Petty squabbles over logistical support with Russian military leadership escalated to claims of outright conflict between Wagner and regular forces. Perhaps nothing better illustrates the animosity between the two than the purported outreach by Prigozhin to Ukrainian intelligence services to provide targeting data for Russian military leadership on the front. Reporting over the past week suggested that Wagner, which had suffered extreme losses during the months-long effort to take Bakhmut and was reconstituting, would be absorbed by the military in the coming months. This would strip Prigozhin of his power base and leave him horribly exposed within Putin’s retinue.

If he was truly an insider, Prigozhin’s antics would be unnecessary: he could sway Putin directly towards his objectives. Prigozhin however has clearly lost standing, and his public messaging reflected that: he was trying to influence Putin, as well as the Russian people more broadly to pressure the centre.

The reasons behind Prigozhin’s fall are not clear to us. Perhaps he had promised to deliver victory in Bahkmut, only to lose 20,000 soldiers for almost no gain. Unlike the military with its institutional recruitment system, Wagner exists largely at the behest of Putin himself. Thus, non-performance would threaten its ability to get resources and troops.

One scenario many fail to consider is perhaps whether this is a crisis borne out of a miscalculation by Prigozhin. He had the perception of losing his position, which led him to undertake riskier actions to regain his stature. This in itself may have created a self-fulfilling prophecy: those actions further alienated his benefactor, leading to the spiral downward that hit the ground over the weekend.

The actual import of Prigozhin’s failed action will take weeks or even months to come clear. In terms of Kremlinology, it may be limited. The diffusion of power is designed to ensure that no one person other than Putin is invested in too much power, and this in some ways is how the failsafes are supposed to work.

Prigozhin’s exile removes the immediate problem for Putin. It ended an outbreak of violence that would have pierced many narratives about the Kremlin’s control and severely damaged regime stability. The fact that Wagner will continue to operate outside of Russia, where it played an important role in advancing Russian interests, perhaps means that Prigozhin’s utility for Putin may not be at an end. Alternatively, he may join a long list of exiled individuals assassinated by the state once their profile declined domestically, most notably Leon Trotsky.

Still, the image of Wagner troops taking a major city and approaching within several hundred kilometres of Moscow is a hard one to shake. Putin controls almost all of the media outlets, and has been able to blunt some wider damage. Nevertheless, the mutiny reveals the underlying cleavages in Russian society that many have suspected existed for quite some time.

Significant segments of the population are not happy with the direction of the war, Putin’s leadership, and the country itself. Fear and repression are a core part of the state’s control system that papers over these sentiments. Strip that away and the population may be more likely to rebel. It’s an important consideration as this war drags on to 15 months. Moreover, Wagner’s ability to move quickly throughout the country illustrates just how focused the military and state apparatus are on the Ukrainian war.

If one believes that Putin is aware of his regime’s vulnerabilities, then perhaps he may be more willing to accept unfavourable terms to get out of a losing position. His deal with Prigozhin illustrates his ability to pivot to get out of a bad position when necessary. Then again, Putin may also feel like he’s currently backed into a corner, and any settlement made at this point that does not reflect some of his maximalist goals for the country would be unpalatable for his regime’s stability. Thus, he will continue to push Russia into this unbelievably ruinous conflict until he can achieve them.

The West’s approach to this all should be to hold the course, to continue to provide resources to Ukraine, and to drive home its collective commitment to ultimate victory. Trying to manage the vagaries of Kremlinology and Putin’s whims will lead to erroneous conclusions. Rather, ensuring that Moscow understands that nearly all potential outcomes for Ukraine will not result in any potential benefit to Russia or Putin himself may force them to contemplate cutting their losses and ending this disastrous conflict.

Richard Shimooka is a Hub contributing writer and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute who writes on defence policy.