This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, January 19, 2023

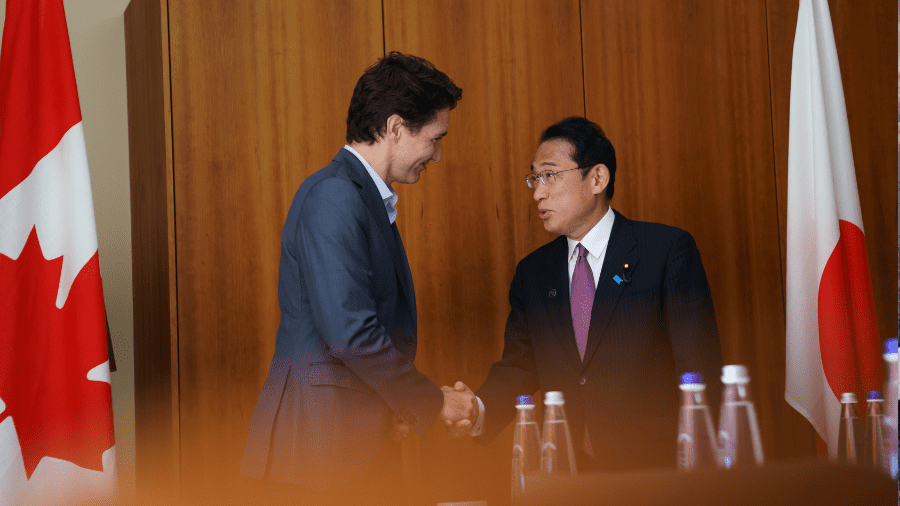

Last Thursday, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida visited his Canadian counterpart Justin Trudeau in Ottawa to capstone a deepening relationship between their two countries.

The closer ties began five years ago with the partnership in bringing forward the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and evolved with successive commitments for the two democracies to contribute to a free and open Indo-Pacific region.

Seen alongside the Canada’s recent Indo-Pacific Strategy, the Japan-Canada cooperation underscores the importance of the region and that both countries share values including freedom, democracy, human rights and rule of law.

Despite these overlapping interests, Japan and Canada’s partnership remains an important but underperforming relationship. This underperformance is related to their foreign policy focus within the Indo-Pacific, their challenges within the region and their identities as middle powers vs. major or great powers.

Focusing on identity, Japan continues to see itself as a great or major power. As a consequence of power, it has an important role in shaping international institutions and the Indo-Pacific region more broadly.

This argument is not without merit. It was former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe who tabled the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” concept linking the Pacific and Indian Oceans in his “Confluence of Two Seas” speech in India in 2005. Through his leadership, the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” vision began to evolve. Today, the concept of such an Indo-Pacific region is welcomed by the European Union, Germany, the Netherlands, France, the U.K., the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, ASEAN, as well as Canada.

In contrast to Japan’s vision or understanding of itself as a great power, Canada continues to see itself as an influential middle power. For example, in January 2017, Canada convened a group of middle powers as well as the United States in Vancouver to discuss the denuclearization of North Korea. In late 2020, Canada put together the Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in State-to-State Relations to push back against hostage diplomacy and the detention of citizens after the arrest of two Canadian nationals in China.

These middle power diplomatic endeavors are indicative of Canada’s commitment to investing in the international order through proactive dialogue and working with other middle powers.

The challenge for these two countries is that while Canada lives in a relatively stable geopolitical and geoeconomic environment, Japan sits in a very volatile neighborhood surrounded by China, Russia and North Korea.

These two different geopolitical environments mean that Japan and Canada have very different priorities in terms of how they look at the Indo-Pacific. Japan sees a stable and prosperous future that is linked to inculcating itself into the political economy of the region. This means helping shape and defend the rules-based order against revisionist states.

Its difficult geopolitical environment and its domestic challenges in terms of demographics require Japan to be forward leaning, realistic and pragmatic to deal with its Indo-Pacific challenges. Canada on the other hand, residing in an much more agreeable geopolitical environment, leans towards progressive foreign policy choices under Prime Minister Trudeau, including its feminist foreign policy agenda, which aims to improve the inclusiveness of women and minorities in all aspects of Canada’s foreign policy abroad.

While these are important and meaningful priorities for Canada domestically and in its foreign policy towards Scandinavian countries and Europe, these progressive foreign policy priorities do not play well within the Indo-Pacific and they do not overlap well with the Japanese priorities within the region.

In this sense, Japan and Canada must better harmonize their priorities and be more realistic about where they overlap. As the third largest economy in the world, Japan represents an attractive opportunity for Canada to engage within the Indo-Pacific region. This engagement must include energy and critical mineral security in which Canada provides stable flows of energy to Japan and other like-minded countries within the region.

Working together diplomatically is also critical as Tokyo and Ottawa aim to strengthen their relationship. Japan’s new National Security Strategy provides a platform for Canada to engage with the Asian power.

Key areas to invest in could localize the framework of the strengthening relations between Australia and Japan in terms of the reciprocal access agreement. Additionally, acquisition and cross serving agreements as well as agreements concerning the transfer of defense equipment and technology, enhanced military, bilateral and multilateral training exercises, defense equipment and technology cooperation are also key areas in which Japan and Canada can continue to cooperate.

With Canada already, having secured federal budgets for artificial intelligence related quantum computing and cybersecurity cooperation, it seems natural for Canada to work much more closely within the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (comprising Australia, India, Japan and the United States) and AUKUS (Australia, the U.K. and the U.S.) to enhance the capabilities of these and to integrate them with other lateral organizations.

Other important areas for Canada to work with its Japanese partner is in strengthening cooperation in terms of multilateral diplomacy such as in enhancing the coalition against arbitrary detention. Working on cyber cooperation, helping develop norms to use cyber weapons and regulatory regimes in a way that creates opportunities for Canada and Japan to provide value to these regimes within “the Quad” and AUKUS partnerships is also a viable area of cooperation.

Lastly and importantly, both Japan and Canada need to enhance their economic relationship. Enhancing such economic ties means there need to be more high-level visits by Japanese and Canadian business leaders and ministers to each other’s countries. It could mean leveraging some of the initiatives that have been laid out in Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy such as the Gateway Asia, Canada’s Science, Technology and Innovation partnerships with Japan, South Korea, India, Singapore and Taiwan to provide a platform for Canadian businesses to enhance its engagement with Japan. This must include understanding Japan as a platform for engagement in the broader region.

Working alongside the Japanese Business Federation, JICA and JETRO, there are important synergies that can be leveraged to enhance Canadian presences in Japan, but also the broader region.

Upgrading ties between Japan and Canada will require leadership, commitment and prioritization on the relationship to help both countries realize their respective Indo-Pacific visions.

Stephen R. Nagy is a senior associate professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a senior fellow at the MacDonald Laurier Institute, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.