By Kyoko Kuwahara

April 26, 2023

With the advance of globalization and the rapid development of information and communication technology as well as artificial intelligence (AI), public opinion has played an increasingly critical role in the policy-making process of governments. Many countries, including China, are well aware of these phenomena and are stepping up their efforts to approach and even influence public opinion in other countries, including the United States, which plays a critically important role in international agenda-setting.

There are two major types of activities in shaping global public opinion. One is orthodox public diplomacy that is aimed at improving a government’s image and the image of the nation as a whole in foreign countries. The other consists of operations to manipulate or affect the decision-making, beliefs, and opinions of a target audience. Today, the latter type of activities is the focal point, and are often criticized by the West as foreign interference.

This paper examines the current state of foreign influence operations[1] in Japan, particularly how foreign countries undertake such operations and the evolution of Japan’s approach to such campaigns. It concludes with some thoughts on the implications for Canada.

How Japan’s neighbours approach global public opinion and its impact

It is well recognized that Japan is a natural target of Chinese influence operations given its geographical proximity, economic weight, and place in the US-Japan alliance. In Japan, however, with cultural and linguistic characteristics serving as barriers, there has been a lack of recognition that public opinion in Japanese society is seriously affected by influence operations from abroad. As will be discussed in more detail, while there is certainly concern within Japan about China’s covert approach to some Okinawan residents, insufficient resources have been devoted to analysing and addressing Chinese influence operations. Rather, the Japanese government has focused its efforts on countering foreign influence that could undermine Japan’s profile in the international community.

It was under the second Abe government, which took office in December 2012, that Japan became aware of foreign influence to shape international public opinion and thereby create an information environment that was not favourable to Japan’s national interests. At that time, the conflict between Japan and China was intensifying over the territorial sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands.[2] Japan nationalized the Senkaku islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese) in September 2012, and China protested sharply against the nationalization and carried out aggressive propagandistic activities in the US, arguing that Japan was the one who took provocative actions in the disputed islands.

When the Abe government challenged the notion that Japanese Army was responsible for the “comfort women” during the Second World War, South Korea brought this issue to US audiences. South Korea, occasionally working with China, embarked upon anti-Japan lobbying activities, labelling the Abe government as a revisionist attempting to rewrite and whitewash history through the justification of the Japanese Army’s criminal acts against women during the war. South Korean organizations started the movement to install comfort women memorial statues across the US and major US media outlets such as the New York Times, also known as a media agenda-setter (McCombs 2004), began to take critical views against Abe as a hawkish nationalist (New York Times 2012; 2013).

China and South Korea, in short, were engaged in vigorous anti-Japan measures to influence the US government decision-making process, the media as an agenda-setter, and even American society. They were advancing strategic approaches in the US and were successful in their attempt. Over the past decade, Japan has tried to recover its profile, and made significant efforts in public diplomacy as a means to reach out to foreign public opinion, especially in the US.

Countermeasure since the second Abe government

The second Abe government came to view this situation in the US as a serious crisis for Japan’s profile, and started a vigorous public diplomacy effort to reach out to American audiences. Its approach was mainly to counter Chinese and South Korean’s criticism by refuting their arguments and justifying Japan’s position. Japan’s approach with China and Korea has often been referred to as “information war over the interpretation of history” (歴史戦).

In other cases, especially on the diplomatic front, the Japanese government has focused on soft power. Since the second Abe government, there has been an increase in cultural and people-to-people exchanges, in addition to government communication activities. Most of these approaches are aimed at maintaining and enhancing trust and favourable views of Japan from abroad. These approaches, so far, have enhanced the international reputation of Abe’s diplomacy and Japan’s soft power, and led to a relative decline in the critical tone against Japan’s stance, especially in major western media coverage, although other factors may have played a role as well.

Chinese influence operations in Japan

Since the second Abe government, Japan has focused on countering foreign influence operations in the US and those related to Japan’s profile. Importantly, the government has not taken any special measures against influence operations that target Japanese audiences. On the other hand, foreign influence operations have not been completely absent in Japan. China is often pointed to as the biggest potential threat to Japan in this context. Recently, the presence of two Chinese “police stations” in Tokyo has raised concerns within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.

There are two main types of Chinese influence operations methods in Japan: covert means, such as police stations mentioned above, and overt means, such as those conducted by the Chinese government.

As for other covert means, China has also pushed a narrative that Okinawa was originally an independent state called Ryukyu that was subordinate to the Qing Dynasty. In 2013, the Global Times argued that China could potentially foster “forces that seek in Okinawa the restoration of the independence of the Ryukyu Chain” (Global Times 2013). A recent report by Japanese Public Security Intelligence Agency (2017) pointed out that some Chinese universities and think tanks were interested in the “unsettled theory of Ryukyu’s belonging” and were promoting exchanges with Japanese group officials advocating “Ryukyu independence.” The Institute for Strategic Research (IRSEM), in its 2021 report, also noted that Beijing supports some movements by those opposed to the US presence in Okinawa and those opposed the revision of Article 9 of the Japanese constitution and the reinforcement of Japanese self-defence capabilities. As the report goes on to note, Okinawa tends to be recognized as “a fertile ground” (Charon and Jeangène Vilmer 2021) for foreign influence operations because of the presence of its large US bases, and its constant disagreements with the Japanese central government.

In recent years, the National Police Agency (NPA) has stated in a public report that China has been conducting information-gathering activities in Japan through sophisticated and diverse means, such as sending engineers, researchers, and students to companies that possess advanced technology, defence-related companies, and research institutes. The NPA also reported that Chinese government, business, and university officials are actively visiting Japanese companies and other organizations that possess cutting-edge science and technology, and are using various opportunities to encourage them to enter the Chinese market, conduct joint research, and make their technology available.

Furthermore, in its latest report in 2023, the NPA noted the possibility of so-called “Operation Foxhunt” by the Chinese government in Japan. Operation Foxhunt is a Chinese government campaign to target wealthy Chinese individuals who were accused of corruption and had fled the country. It involves harassing, intimidating, and coercing such residents to return to the People’s Republic of China.[3]

As for overt means, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has increasingly used Twitter to target Japanese Twitter users in an effort to disengage Japan from the US. For example, in April 2021, the Chinese Embassy in Tokyo tweeted a criticism of the US that the “democratization” of “Iraq,” “Libya,” “Syria,” “Egypt,” and others by the US could be compared to the Grim Reaper. This tweet attracted a great deal of attention on Japanese Twitter.[4]

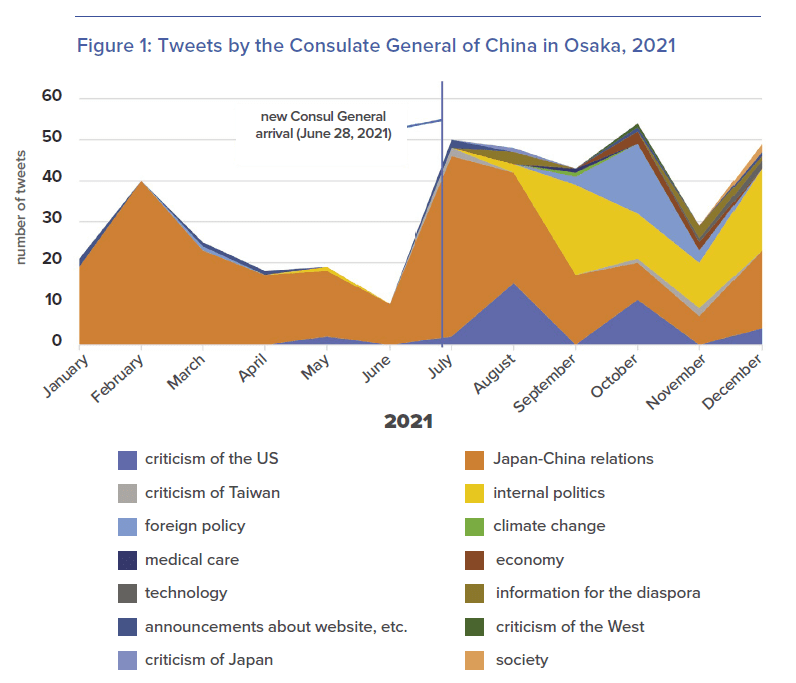

In recent years, China has been pursuing so-called “wolf warrior diplomacy,” or diplomacy in which it loudly asserts itself, and the Chinese government’s belligerent tweets are indeed one example of that behaviour. The Consulate General of China in Osaka also experienced a surge in tweets by criticizing the US and touting China’s core interests after Xue Jian was appointed as the new consul general (Figure 1). Consul General Xue Jian also uses the Osaka dialect, which is characterized as sounding more melodic and friendlier than standard Japanese, to address Japanese Twitter users.

It was not until the global spread of COVID-19 in 2020 that China began to take this belligerent and overt approach to influence Japanese public opinion. The pandemic triggered increasing calls for China’s responsibility from the world, and severely damaged China’s reputation. On August 13, 2021, Chinese Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Ma Zhaoxu accused the US of threatening and coercing the Secretariat of the World Health Organization and international experts with its criticisms that the COVID-19 had indeed originated from China.

It is believed that China is continuing to criticize the United States in Japan as well, with the aim of clearing its own name and diminishing Japan’s trust in its US ally. Indeed, the Consulate General in Nagasaki and other diplomatic missions in Japan are also sending out messages on their official websites and other media expressing their firm opposition to the “politicization” of the virus’ origin.

Assessing the impact of China’s influence campaign

However, it is commonly recognized that China’s approach has not been effective in Japanese society and, in many cases, has had the opposite effect. For example, the tweet from the Chinese Embassy in Tokyo was widely criticized by Japanese Twitter users for being “ungracious,” and in response, the Chinese Embassy itself deleted the tweet. The US Embassy in Tokyo (2021) also posted on its official Twitter account, “Thank you to our Japanese friends for calling out that repulsive tweet. This is yet another reminder that the US-Japan alliance is deeply rooted in shared values.” In addition, the aforementioned “wolf-warrior” tweet from the Consulate-General in Osaka received mostly negative comments from Japanese users, and given the slow increase in the number of followers, it cannot be said to have had much positive influence in shaping Japanese public opinion online either. Therefore, it can hardly be said that China’s more hardline approach has led to the acquisition of Chinese supporters, at least in Japan’s information space.

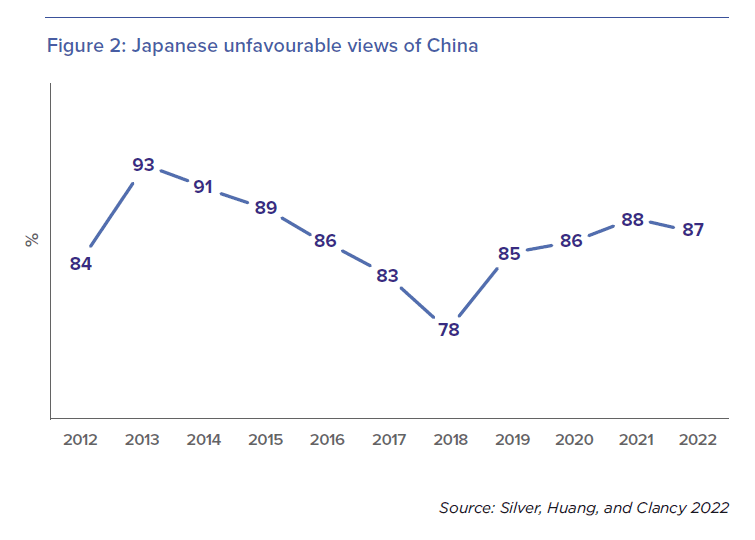

China’s inability to penetrate Japanese society and exert a significant influence in shaping Japanese public opinion can be attributed to several reasons. First, territorial dispute and aggressive Chinese actions, such as sending Chinese government ships to the coast of the Senkaku Islands, irritated most Japanese people, which is reflected in Japan’s negative public opinion toward China (Stewart 2022). According to the Pew Research Center’s 2022 public opinion survey, 87 percent of Japanese respondents answered that they have an unfavourable view of China, which is about the same as in previous years (see Figure 2).

Second, the low presence of foreign media in Japan also helps explain why it is difficult for foreign actors to penetrate the Japanese information space. Certainly, the presence of China Watch, an advertisement published by China Daily of China, and Sputnik News of Russia are recognized in Japan as a tool of information warfare by these governments, but the presence of foreign media in Japan still remains low. In Japan, small number of Japanese media companies are quite dominant in the society. Six media giants – NTV (Yomiuri Shimbun), TV Asahi (Asahi Shimbun), TBS (Mainichi Shimbun), Fuji TV (Sankei Shimbun), TV Tokyo (Nikkei Shimbun), and NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) – dominate the Japanese media environment, making it difficult for foreign media to make a significant impact in the country (Stewart 2022).

In fact, a 2022 public opinion survey by Japan Press Research Institute showed that Japanese people’s trust in each media outlet remains high,[5] with NHK TV coming in first at 67.4 out of 100 and newspapers second at 67.1, indicating that trust in traditional media continues to be quite high in Japan. In terms of daily contact with the news, the highest contact rate was 88.8 percent for commercial broadcasting news, 75.0 percent for Internet news, and 74.4 percent for NHK TV news, which reveals a higher contact rate with traditional media than with the Internet.

Third, as mentioned above, Japan has historically, culturally, economically, and linguistically been relatively isolated from the rest of the world, making it less susceptible to foreign influence (Stewart 2022).

Japan’s policy shifts and prospects

The Japanese government’s interest in foreign influence operations has long been oriented toward what impact foreign countries were having on global public opinion. If it judges the influence to be a crisis for Japan’s profile, the government has made effort to prevent its impact. Since the second Abe government, priority has been given to countering anti-Japan campaigns being waged by China and others in the international community, and to approaching international audience through its public diplomacy. However, as globalization further progresses, AI technology advances, and the information space diversifies further, Japan itself could become vulnerable to the potential foreign influence operations.

In particular, AI has been used for influence operations, enabling the mass generation of disinformation or malinformation and making it more difficult to distinguish between what is true and false, which may further disrupt society. The new National Security Strategy clearly stated that Japan should proactively respond to foreign disinformation campaigns and information warfare even during peacetime. In other words, Japan will now focus more on countermeasures against foreign influence operations in Japanese society. Factors that may have influenced this shift in agenda-setting by the Japanese government include the spread of COVID-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and rising military tensions around Taiwan.

It is important for Japan to broaden and improve its security perceptions of foreign influence operations. We can expect research on foreign influence in Japan will advance in both the public and private sectors. In this process, criteria should be established to distinguish between highly transparent approaches, such as public diplomacy, and opaque interference, such as manipulation and cognitive warfare, to clarify how to deal with each. In addition, government, industry, and academia should work together to manage security risks in research and technology development. At the same time, it is also essential for Japan, along with its allies and partners, to communicate with and approach the Chinese diaspora in a way that can promote their understanding of both Japanese and western ideas.

Implications for Canada

Like Japan, Canada has not been a major target of sophisticated foreign interference or influence operations in the past. However, as the security environment in the Indo-Pacific region has changed and influence operations disinformation have expanded into cyberspace, both Japan and Canada have begun to be subject to increasing foreign influence operations from countries like Russia and China.

Currently in Canada, in addition to the threat of Russian disinformation campaigns against Canadian civil society, there is growing concern about the threat of Chinese “interference,” exemplified by allegations of interference in the 2019 and 2021 elections. In general, possible measures to counter foreign interference activities include enhanced cybersecurity, legislation such as Taiwan’s “anti-infiltration act,” literacy education, and advocacy for vulnerable groups. However, as a prerequisite for taking appropriate measures, the specific methods of foreign interference or influence operations, the threat level (apparent or potential, short-term or long-term, whether urgent measures are required or not), and the actual impact must first be objectively investigated, analysed, and evaluated. It will also be necessary to consider existing social narratives as well as groups, regions, and age groups that are vulnerable to such interference.

On the other hand, there remains a challenge in this process: it is extremely difficult to quantitatively assess this issue, such as the percentage of citizens affected by foreign interference and influence operations. This is due to it being a battle over human cognition, including human will, perceptions, beliefs, values, and ideas.

In Japan, although the threat of Chinese influence operations is primarily discussed, there is no framework in place to conduct objective research, analysis, and evaluation, as mentioned above. While Japan is expected to make efforts to create such a framework, Canada should also learn from the Japanese situation. As domestic medium- to long-term measures, it is recommended that Canada improve its journalism, promote literacy education, advocacy, and opportunities for human exchange, and as external measures, it should promote the sharing of lessons learned with Japan and other countries and regions in the Indo-Pacific.

About the author

Kyoko Kuwahara specializes in public diplomacy, strategic communications, disinformation and soft power strategies. She is a research fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, and a visiting fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. She also serves as a visiting research analyst at the Institute for Future Engineering in Tokyo, a specially appointed assistant professor at Kyoto University, and a 2023 Schmidt Futures International Strategy Forum Fellow.

After completing a master’s course at the Osaka School of International Public Policy, Osaka University, she joined the Sasakawa Peace Foundation, where she was a research fellow in 2017-2018. She then served as an officer at the Office for Strategic Communication Hub at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan in 2018-2019 before joining the JIIA.

Her recently published books include Naze Nihon no “Tadashisa” ha Sekai ni Tsutawaranai noka: Nichi chū kan Shiretsu na Imēji Sen (Why is Japan’s “Righteousness” Difficult to Convey to the World? Fierce Image Competition between Japan, China, and South Korea) (2020), and Nise Jōhō Sensō: Anata no Atama no Naka de Okoru Tatakai (Disinformation Warfare: The War in Your Heads), co-author (2023). Her most recent published articles include ‘Disinformation Threats during a Taiwan Contingency and Countermeasures’ (Research Report, the Japan Institute of International Affairs, March 22, 2022), ‘Fighting Disinformation: Japan’s Unique Situation and The Future of Canada-Japan Cooperation’ (MLI Commentary, Macdonald-Laurier Institute, November 2021) and ‘The Disinformation Threat and International Cooperation’ (JIIA Strategic Comments, the Japan Institute of International Affairs, June 2, 2021).

References

Charon, Paul and Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer. 2021. Chinese Influence Operations: A Machiavellian Moment. Institute for Strategic Research, October. Available in https://www.irsem.fr/report.html.

Global Times. 2013. “Ryukyu issue offers leverage to China,” Global Times (May 10). Available athttps://www.globaltimes.cn/content/780732.shtml.

Japan Press Research Institute. 2022. “Media ni Kansuru Zenkoku Yoron Chcsa Kekka no Gaiyō (Summary of National Public Opinion Poll Results on Media).” Japan Press Research Institute, November 12. Available at https://www.chosakai.gr.jp/wp/wp-content/themes/shinbun/asset/pdf/project/notification/yoron2022press.pdf.

Japanese Public Security Intelligence Agency. 2017. Annual Report 2016 Review and Prospects of Internal and External Situations. Public Security Intelligence Agency, January. Available at https://www.moj.go.jp/content/001221029.pdf.

McCombs, Maxwell. 2004. Setting the Agenda: The Mass Media and Public Opinion. Cambridge: Policy Press.

New York Times. 2013. “Another attempt to deny Japan’s history.” New York Times (January 2). Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/03/opinion/another-attempt-to-deny-japans-history.html.

New York Times. 2012. “Shinzo Abe’s Second Chance in Japan.” New York Times (December 19). Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/20/opinion/shinzo-abes-second-chance-in-japan.html.

Silver, Laura, Christine Huang, and Laura Clancy. 2022. “Negative Views of China Tied to Critical Views of Its Policies on Human Rights.” Pew Research Center, June 29. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2022/06/29/negative-views-of-china-tied-to-critical-views-of-its-policies-on-human-rights/.

Stewart, Devin. 2020. “China’s Influence in Japan: Everywhere Yet Nowhere in Particular.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July. Available at https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-influence-japan-everywhere-yet-nowhere-particular.

US Embassy in Tokyo (アメリカ大使館): @usembassytokyo. 2021. Tweet, April 30, 9:00 am. Available at https://twitter.com/usembassytokyo/status/1388116054266683393?s=20.

[1] In Japan, the term “interference” is rarely used in this context, and is instead often referred to as “influence operations.”

[2] The Japanese government does not recognize the existence of any international dispute over the territorial sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands. For further information in Japanese on this report, see https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/c_m1/senkaku/page1we_000010.html.

[3] Both reports are available on the NPA website here: https://www.npa.go.jp/bureau/security/publications/syouten/291/291.pdf and https://www.npa.go.jp/bureau/security/publications/syouten/293/R4syouten.pdf.

[4] While the original tweet was deleted, some Japanese media put its screenshot online and it is available here: https://www.sankei.com/article/20210430-4QVL4S364FMCTPP7KOBFEJBW7A/.

[5] The survey results are available in Japanese at https://www.chosakai.gr.jp/wp/wp-content/themes/shinbun/asset/pdf/project/notification/yoron2022press.pdf.