Adopting single-payer coverage is not the solution to the challenges facing Canada’s pharmacare system, writes Sean Speer.

Adopting single-payer coverage is not the solution to the challenges facing Canada’s pharmacare system, writes Sean Speer.

By Sean Speer, May 2, 2018

The idea of creating and implementing a national pharmacare program seems to have climbed to near the top of the policy agenda in recent weeks. The announcement of an advisory panel to study the subject in February’s budget has since been followed by a parliamentary committee report that favours a single-payer pharmacare scheme and an expression of support by Liberal Party members at their recent policy convention. Meagan Campbell predicts in Maclean’s that this issue will loom large in the 2019 federal election.

There’s good reason for policymakers to focus on improving the financing for and access to pharmaceuticals. There are gaps in the current model of health insurance in general and drug coverage in particular, and room for improvement in the current funding model to reflect changes in medical technology, demographic pressures, and public needs. But it doesn’t follow that the solution is to establish a federally run, single-payer system.

This is the crux of the debate over the coming months. The two poles are represented by the MPs on the health committee who endorsed first-dollar, single-payer coverage on one side and Finance Minister Bill Morneau who has said any new initiative should seek to fill “gaps” in the current financing and insurance model on the other. This brief commentary sides with Mr. Morneau in this important policy debate.

Canada’s health care anachronism

Most of the basic architecture of the health care system – including delivery and financing – remains unchanged since the early days of Medicare. Yet almost everything else, from care protocols to technology, has changed.

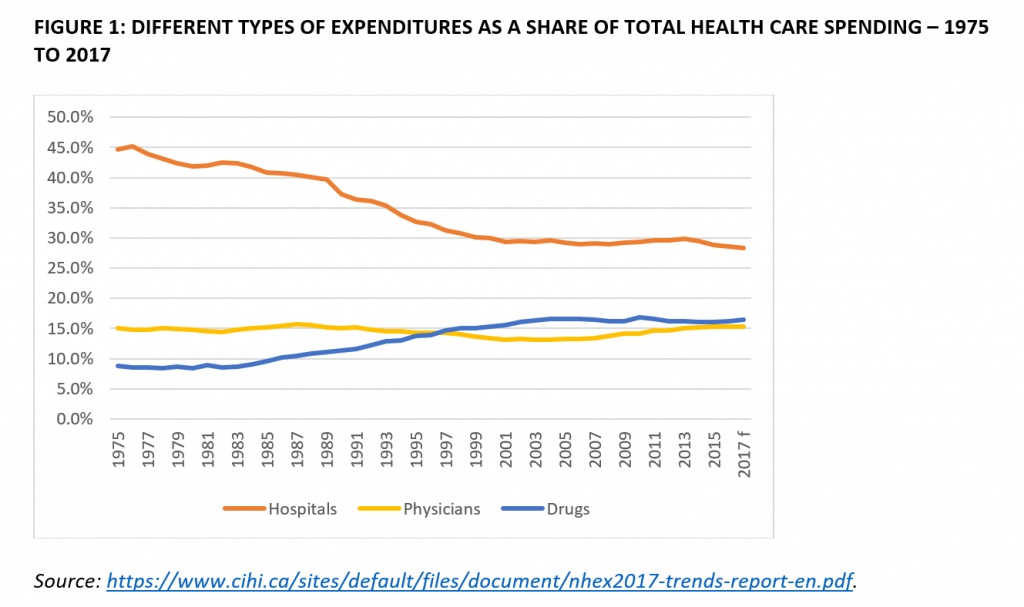

One example: while pharmacological innovation has markedly improved health outcomes, it has also changed how health care is delivered, and the mix and composition of health care spending. Drugs became the second largest health care expenditure roughly two decades ago (see figure 1). The annual growth of expenditures for drugs has exceeded hospital and physician spending in recent years.

Remember that Canada’s public insurance model is, by and large, limited to hospital and physician services. Drugs and many other health related costs are generally only covered when they are incurred in hospital. This is an anachronism that fails to reflect the growing and increasingly critical role of pharmacology in modern medicine. The “biotechnological revolution,” as it is sometimes called, post-dates the advent of Medicare.

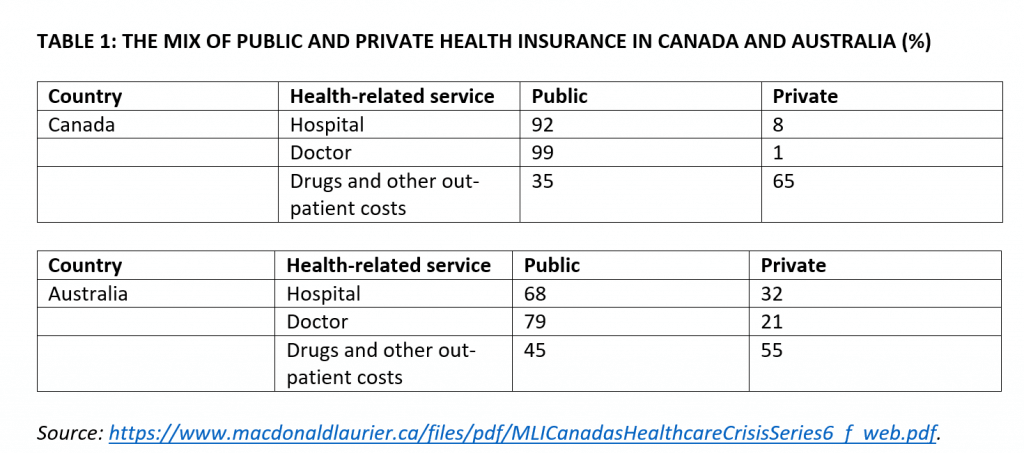

The current mix between public and private spending on health care (see table 1) has been largely frozen for nearly half a century. It makes Canada an outlier relative to our peers. Public insurance essentially covers 100 percent of all hospital and physician services, but is highly limited in other areas of health care spending including drugs, dental, and outpatient care. MLI has previously described Canada’s single-payer model as a “mile deep and an inch wide.”

Think about this statement for a minute. Hospital and physician spending represents less than half of Canada’s health care expenditures. So essentially we have full public coverage for half of our health care system and little to no public support for the rest. And the non-insured share of the system is growing faster than the insured share.

Other jurisdictions, by contrast, provide less generous public insurance but are able to extend coverage to a wider range of health-related services. Australia is a good example (see table 1).

The case for rethinking health care financing

As mentioned, there’s a case for rethinking drug financing and insurance coverage in light of the rising role of pharmacology in our health care system, the interaction of new medical innovation with the single-payer system, and the growing unsustainability of the overall model. Examples include:

- New oral-administered drugs enable patients to receive treatment at home rather than in the hospital, but the insurance model (which covers drugs administered in hospital but not at home) can create perverse incentives whereby treatment choices are driven by financing instead of medical considerations.

- Out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs is climbing. It currently represents more than 20 percent of prescription drug spending in Canada. This amounts to an average of $476 per household. These costs are disproportionately borne by the lowest-income households.

- Efforts to control drug costs have been ramped up – including a new pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance involving the provinces and territories to enable bulk negotiations and purchasing by the provinces. The focus of the efforts has generally been on better controlling costs for provincial governments.

- Political pressure is mounting for governments to find new and different solutions to help individuals cover the costs of drugs. One of these solutions is the adoption of the national pharmacare model mentioned earlier.

- Public spending on health care has become increasingly unsustainable. It now averages about 40 percent of total provincial spending and MLI research shows that in several provinces it will soon exceed 50 percent.

- The Parliamentary Budget Office has judged that every province except for Quebec and Nova Scotia are presently facing long-term fiscal sustainability challenges – the gap ranges from 0.4 percent of GDP in Ontario to 7.2 percent for the Territories.

The case for reform, then, is strong: some of the systemic perversities caused by the current model and the growing unsustainability of its overall funding model must be addressed.

But the need for reform does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that we ought to move to single-payer coverage for drugs. Not only would it be massively expensive – the Parliamentary Budget Office estimates its cost at more than $20 billion per year – but it threatens to disrupt the parts of the system that people are used to and that they like and want to protect. The lesson from the Obamacare experience in the United States is that health care reform must be deliberate and incremental if it is to survive the political process and secure public buy-in.

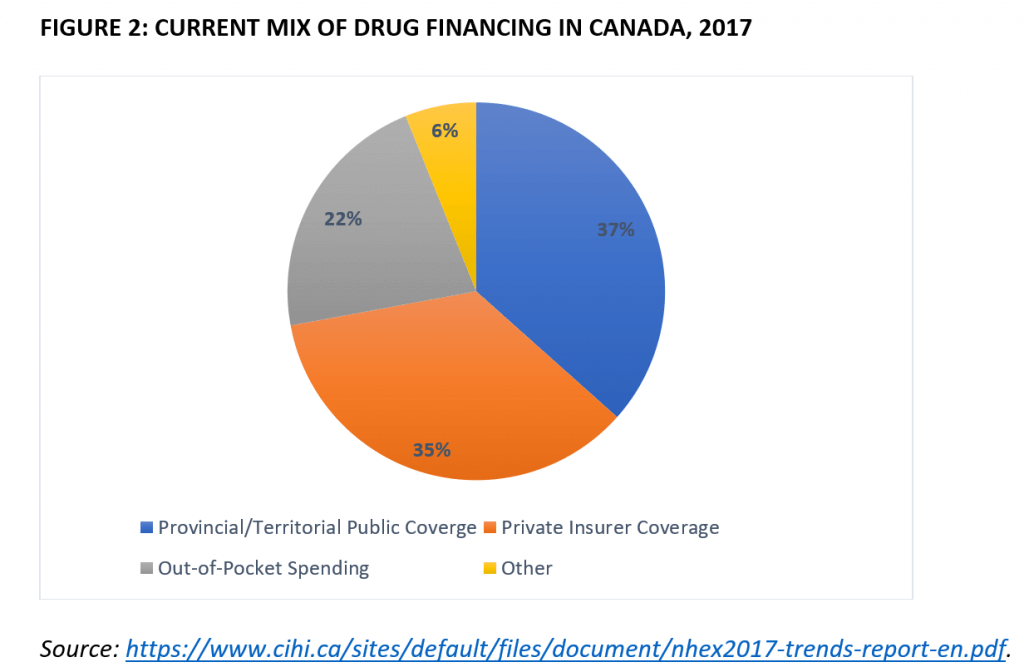

Put it this way: private insurance currently makes up $12 billion of the $34 billion spent on prescription drugs each year (see figure 2). Canadians who are currently covered by these plans would likely see a decline in their coverage under a mandatory, single-payer plan because the federal formulary would invariably be more limited than what is offered under current private plans. How is that the basis for a successful and durable reform?

It’s a losing political and policy strategy to tell 35 percent of the population that they cannot keep their prescription drug plans even if they like them, especially since many of these benefits have been won through collective bargaining. One can envision various court challenges if the government(s) sought to impose a one-size-fits-all public insurance scheme. We cannot and should not merely graft single-payer coverage onto the pre-existing regime.

Filling gaps in Canadian drug coverage

Rejecting the idea of a mandatory, single-payer plan doesn’t mean that there’s no room for reform. Canadian governments should look to “fill gaps,” as Finance Minister Morneau has put it, in order to strengthen the current model.

The Ontario government’s recent move to OHIP+ is a flawed yet general step in this direction. The province has moved to provide first-dollar coverage for prescription drugs for Ontarians ages 24 and under.

It’s the type of incremental, targeted solution that policymakers ought to consider. But, as I have written elsewhere, the focus on age – particularly on an age group that’s generally healthier and tends to use fewer prescription drugs – seems like an odd solution. It’s especially perverse from an equity standpoint. Why would a wealthy 24-year-old be eligible but a poor 25-year-old not?

Instead, there’s room for more holistic reform whereby public insurance is extended to drug coverage based on one’s means in exchange for the introduction of means-tested patient cost-sharing (such as co-insurance, co-payments, or deductibles) across the public insurance model. This would expand Medicare coverage on a pay-as-you-go basis, which would have the benefit of improving equity without further eroding fiscal sustainability.

The idea is far from revolutionary. Many other jurisdictions with universal coverage are able to extend public health dollars across a wider range of services – such as prescription drugs – by implementing patient cost sharing. Caps or exemptions for those with chronic conditions would address concerns about undue costs. The plan would ensure that scarce public resources are targeted for those who most need the help. This just makes sense, especially as the provinces grapple with their long-term fiscal sustainability.

Such a balanced reform would likely require the federal government to enact amendments to the Canada Health Act to enable greater legal clarity and scope for patient cost-sharing. In doing so, Ottawa would be usefully contributing and would also be enabling provincial experimentation and encouraging incremental improvements.

This reform would be a major step toward broader and more universal coverage as well as sustainability and fairness. Experimenting with patient cost-sharing in prescription drugs would enable the provincial governments to test different models and build public awareness that might allow for a future incremental expansion to the rest of Medicare.

Sean Speer is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.