This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, June 21, 2023

Deep mistrust, dysfunction and dissonance characterize the current U.S.-China relationship.

This is bad news as a negative spiral in relations has the potential to intentionally or unintentionally descend into a kinetic conflict that could have consequential ramifications for Japan and the broader Indo-Pacific region.

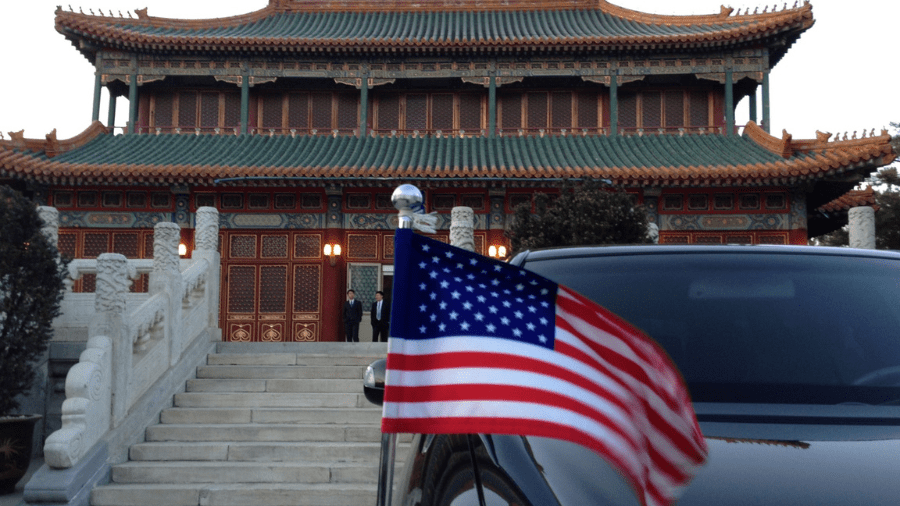

U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s recent visit to China is an important first step to re-establishing dialogue between Washington and Beijing to decrease the chances of a conflict breaking out.

Beijing’s mistrust stems from a perennial insecurity about guaranteeing the longevity of the ruling regime. For leaders in China, they see the U.S. and Western countries’ intentions through the lens of transforming their country into a democracy by the same process U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles advocated for transforming the Soviet Union, which was referred to as “Peaceful Evolution.”

As Sulmaan Wasif Khan writes in his book, “Haunted by Chaos: China’s Grand Strategy from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping,” that since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came into power in 1949 they have navigated what leaders in Beijing understand as a hostile world by leveraging all elements of national power to consolidate their revolutionary government and fragile state.

From Mao Zedong to Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin to Hu Jintao, and now Xi Jinping, they see color revolutions in Hong Kong, Libya and Syria (and even the war in Ukraine) as U.S.-supported initiatives to destabilize China’s political system and to stop its return to centrality in the Indo-Pacific region.

Most critically, they see the U.S. position regarding Taiwan as violating or diluting the “One-China” policy that states the government of the People’s Republic of China is the sole legal government of the country. In short, the PRC was and is the only China, with no consideration of the Republic of China, or Taiwan, as a separate sovereign entity.

As evidence, Beijing cites and denounces the Taiwan Relations Act, which includes a policy of providing the self-governing island with defensive weaponry. The Chinese leadership also lashes out at the growing number of high-level political visits to Taiwan by U.S. and other countries’ politicians, not to mention the issue of Taiwan being woven into international statements such as the recent leaders’ communique from the Hiroshima Group of Seven summit.

In contrast, America’s mistrust stems from China’s opaque political system and values; its efforts to eject the U.S. and its presence from the region; and Beijing’s efforts to rewrite the software of international institutions such as the definitions of human rights and democracy. In the end, it believes the rule of law is weakened.

There are also deep concerns about a growing track record of economic coercion, the abrogating of international agreements such as the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong and rapid militarization. According to a Stockholm International Peace Research Institute study released in 2022, “China remained the world’s second largest military spender, allocating an estimated $292 billion. This was 4.2% more than in 2021 and 63% more than in 2013. China’s military expenditure has increased for 28 consecutive years.”

Importantly, countries from Japan to Canada, Germany to India share similar concerns as the U.S. These shared concerns suggest that the negative spiral in Washington-Beijing relations is not just a U.S. related issue, but has broader, more global implications.

In terms of dysfunction, communication between Beijing and Washington has faltered substantially at least since the latter half of the Trump administration and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

During this period, people-to-people exchanges, particularly from the U.S. to China, dropped substantially. Though tete-a-tete meetings between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping occurred on the sidelines of the Group of 20 summit in Indonesia, meaningful exchanges between scholars, think tanks and policy makers have virtually disappeared for fear of China returning to hostage diplomacy, such as occurred with the 2018 detentions of Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, which many believe were linked to the arrest of Huawei’s chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, by Canada at the request of the U.S.

Hitherto, regular dialogue and visits to each other’s countries provided experts the opportunity to forge better understanding about each other’s security concerns and build crosswalks for cooperation and collaboration. As a professor, I took students to China on study tours to introduce them to different aspects of China’s politics, economy and society.

In the current atmosphere, the aforementioned exchanges are frozen at best. This enhances the dysfunction that exists between not only the U.S. and China but other countries as well. How will the next generation of scholars and policy makers learn about each other’s societies? How do we build deep and broad people-to-people relationships when there are no exchanges? A lack of mutual understanding is a fast track to misunderstanding and conflict.

Dissonance, the inconsistency between the beliefs one holds or between one’s actions and one’s beliefs, also plagues U.S.-China relations, as well as Beijing’s relations with many countries. One example is China’s pro-Russian “neutrality” with regards to its invasion of Ukraine. Other examples include its rejection of the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration’s decision against its territorial claims in the South China Sea; and its policies in Hong Kong and Xinjiang suggest that China’s adheres to its Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence of mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, noninterference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence.

The growing evidence of Chinese influence operations in Canada and Australia and the CCP’s influence on U.S. corporations as cited by Isaac Stone Fish in his book “America Second: How America’s Elites Are Making China Stronger” demonstrate there is a large gap between Beijing’s words and track record.

Similarly, some of the U.S.’ actions and its professed beliefs are hypocritical. For example, abiding by the so-called One-China policy but continuing to support the status quo across the Taiwan Strait. Demanding signatories of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to abide by its mandates while not signing the law itself and criticizing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine despite invading both Iraq and Afghanistan are but a few examples of the U.S.’ dissonance.

Blinken’s visit to China will not overcome the deep mistrust, dysfunction and dissonance that characterizes the U.S.-China relationship. In fact, the deepening economic crisis that is descending upon China, the 2024 Presidential race in the U.S. and boomerang effects stemming from Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine may all worsen these dynamics.

Middle powers such as Japan, Canada, Australia, ASEAN and the EU will need to use their collective diplomatic and economic resources to protect their national interests from Sino-U.S. strategic competition by lobbying both countries to prioritize dialogue and cooperation. They can do this through sponsoring scholarly and think-tank dialogue between the U.S., China and other countries and clearly articulating their concerns to both Washington and Beijing.

Simultaneously, the middle powers have to be realistic, results focused and pragmatic as they insulate themselves from the friction that will emanate from U.S.-China relations through investing the rules-based order in the realms of security, trade and international law.

Dr. Stephen Nagy is a professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, a senior fellow at the MacDonald Laurier Institute, a senior fellow at the East Asia Security Center and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs. Twitter handle: @nagystephen1.