This article originally appeared in the Toronto Star.

By Alex Wilner and Christopher Coates, August 13, 2025

As Prime Minister Mark Carney tackles his pledge to raise Canada’s defence spending to 5 per cent of GDP by 2035, Ottawa should frame this spending around a key goal: deterrence.

Large sums of money are set to flow in order to meet this target — an estimated $150 billion a year once the goal is fully met. As spending ramps up, a focus on deterrence could guide how the government directs these investments and the way that it explains them to Canadians. This would offer a more compelling and constructive frame that meets the geopolitical realities of this moment, rather than merely spending the cash to placate our allies.

Deterrence lives somewhere between peace and war. It entails using retaliatory threats, promises of defeat and other incentives to convince an adversary not to engage in hostilities.

Take a classic example: deterrence kept the Cold War cold by persuading the Americans and the Soviets to avoid open conflict. Warfare between the two superpowers was deemed mutually destructive, too costly and leading to too few benefits to seriously contemplate. Both sides settled for an uneasy status quo. The arrangement stood for decades.

Today, deterrence is faltering. Russia appears perpetually unfazed by efforts to deny it victory in Ukraine. Iran and its proxies have likewise proven undeterred by Israeli military might. China threatens Pacific regional stability by repeatedly undermining Taiwan’s territorial integrity, despite U.S. resolve to protect the beleaguered country.

When deterrence fails, simmering hostilities can too easily slide into open conflict. Human misery, economic volatility and political instability follow.

Avoiding this outcome rests on globally augmenting Western deterrence. The Americans, Europeans, Israelis and Taiwanese clearly understand this need. Their response has been uniform in intent: invest in the tools and procedures that bolster military and civil preparedness to dampen the likelihood of continued and future conflict.

The reason rests on two simple truths. First, global stability hinges on the strength of our collective deterrence. Second, facing an increasingly hostile world, deterrence hinges on our ability to present a convincing military response. Deterrence only functions when would-be adversaries understand our intent and fear our capability.

Canada’s approach to deterrence must match the multi-dimensional nature of contemporary conflict.

Focus on Spending

Here’s how focused spending can achieve this:

• First, Canada must increase its defensive and offensive cyber capabilities and better project its willingness to deploy the latter when threatened.

• We must equip Canadians to avoid and ignore foreign information manipulation. Blunting its utility will make it less attractive for adversaries to interfere in our democracy by these means.

• Civil society’s capacity to respond to myriad emergencies must be bolstered, overtly demonstrating Canada’s whole-of-society preparedness for any contingency.

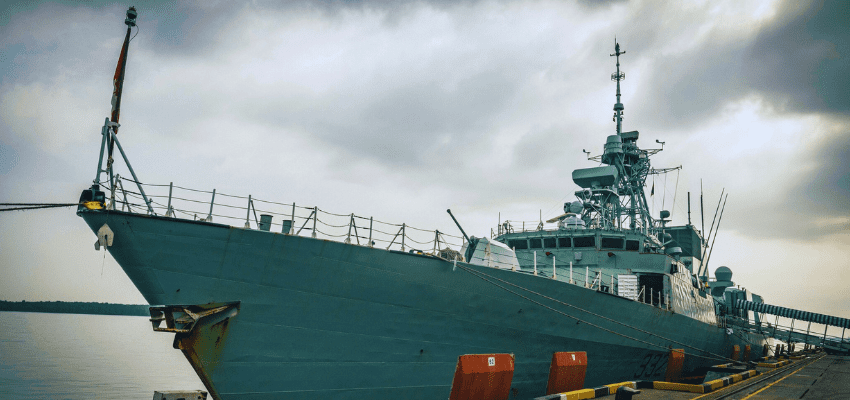

• We must increase self-sufficiency in homegrown weapons development and manufacturing, delinking procurement from external shocks.

• Defence automation and robotics — think about AI and drone warfare — must be expanded, as compelling deterrence tools that have the capacity to change adversaries’ calculus about the wisdom of an attack.

• Canada’s foreign partnerships must be strengthened, highlighting our willingness to stand firm alongside our allies.

• Finally, a better appreciation is needed for the future of warfare more broadly, enabling us to deter and defeat tomorrow’s aggressors today.

On the strategic side, boosting defence spending is about protecting Canadians while changing behaviour: we want to convince adversaries to curtail their aggressive ambitions.

On the economic front, the new spending must be managed in the most cost-effective way: preparing for and deterring war requires far fewer overall resources than fighting and winning one.

On both counts, deterrence provides Canada with a guiding framework for rebuilding our military.

Alex Wilner is a professor at Carleton University and co-director of Triple Helix. He was a member of the 2025 Canadian Academic Delegation to Taiwan.

LGen (ret’d) Christopher Coates is director of foreign policy, national defence and national security at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. He was a participant at the 2025 Transatlantic Roundtable with NATO allies in Brussels.