This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.

By John Gilmour, November 4, 2024

After Israel’s military and intelligence agencies launched devastating and dramatic attacks against Hezbollah in recent weeks, it would be easy to assume the terrorist group has been neutered.

In the last month, air strikes have killed many Hezbollah leaders, including its secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah, who has been a target for decades, and his likely successor, Hashem Safieddine. Exploding pagers and walkie-talkies killed dozens and injured hundreds of Hezbollah members. Now, Israel is working to dismantle the group’s financing wing, throwing it into further disarray.

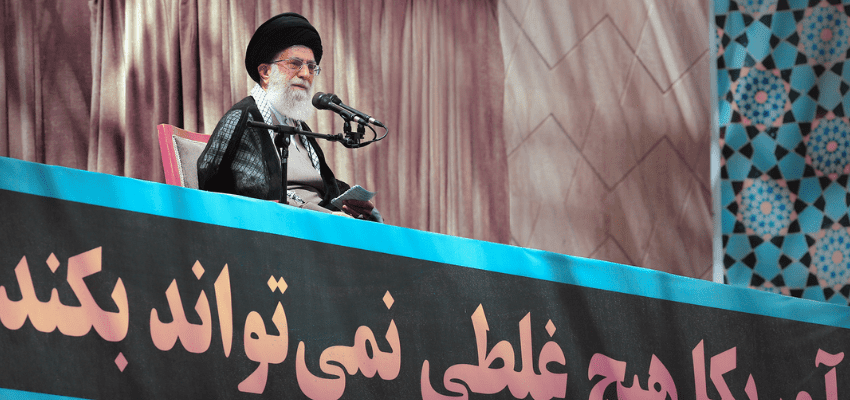

Iran, which has long used the terrorist group as a crucial proxy and deterrent in its conflict with Israel, is now a target of direct Israeli intervention, with Israeli missiles striking Iranian military bases in three provinces last week. But Tehran still has cards to play as part of its broader deterrence strategy – including asking Hezbollah to undertake terrorist attacks overseas, threatening Israelis abroad and Jewish communities around the world.

Since its inception in the 1980s, Hezbollah has built an international network to finance, recruit, arm and plan operations abroad. These cells sometimes co-operate with other terrorist organizations and are entangled in organized crime. Hezbollah’s External Security Organization, which runs these networks from Lebanon, is the lead for terrorist attacks overseas, including in Europe and North America. While the group’s focus remains on Lebanon and Israel, its networks abroad are just as active.

For decades, national-security and law-enforcement agencies have monitored these networks, and intervened when warranted. Hezbollah’s networks are pervasive in virtually all regions, including in the United States and Canada. Indeed, Canadian authorities have described Hezbollah as “one of the most technically capable terrorist groups in the world.”

More ominously, these cells have positioned themselves to undertake attacks against Israeli or Jewish targets worldwide at Hezbollah’s or Iran’s orders if either perceives a threat to their interests or “should the diplomatic situation deteriorate,” according to a British intelligence assessment document. A 2022 George Washington University report noted that “while Hezbollah has not executed a successful attack in the United States, the group still attempts to develop the operational capacity to do so.”

These cells have killed many over the decades, including in the 1985 hijacking of TWA Flight 847, a pair of well-publicized attacks in Buenos Aires on the Israeli embassy and a Jewish cultural centre in 1992 and 1994 respectively, a 1996 attack on a facility housing U.S. troops in the Saudi city of Khobar, and, most recently, the alleged involvement of Hezbollah in a targeted bombing of a bus of Israeli tourists in Bulgaria in 2012. In that particular case, one of the plotters associated with the suicide bomber was a Canadian.

This modest track record hasn’t stopped Hezbollah from trying, however. Authorities have thwarted them on several occasions: an attempt to bomb the Israeli embassy in Bangkok in 1994; a plan to attack Israeli and U.S. targets in Azerbaijan in 2008; plots in Turkey in 2009 and 2011; and preparations to attack Israeli tourists in Cyprus in 2012. A convoy of Israeli diplomats in Jordan also narrowly avoided a roadside bombing in 2020. Threat warnings from Israeli intelligence agencies to Israeli or Jewish communities in Europe, Africa and Southeast Asia occur on a regular basis.

Shortly after 9/11, Hezbollah’s leadership appears to have decided that the best strategy was to use its global network of cells mostly in under-the-radar facilitation roles, such as financing, recruitment, weapons-smuggling and the reconnaissance of possible targets in other countries. Hezbollah leaders in most cases did not see risking exposure by undertaking actual attacks as justifiable in the face of intensified U.S. counterterrorism activities.

But this calculus has likely changed after recent events. Not only might Hezbollah deem it the right time to activate its cells abroad, Iran and its deterrence strategy may call for it.

With Hamas in tatters and Hezbollah on the defensive, Iran’s traditional means of deterring Israel have been undermined. Hezbollah’s fighting wing may quickly reconstitute itself like it did after the Israeli intervention of 2006, but until such a time, Iran is more vulnerable to Israeli strikes, as this weekend’s air strikes proved. As a result, Tehran may seek to rebalance the equation with the asymmetric means of mobilizing Hezbollah’s international terrorist cells.

Western national-security and law-enforcement agencies face a tough task with the uncertainty surrounding the nature and sources of this sort of transnational threat. Canada needs to prioritize counterterrorism efforts against Hezbollah’s global reach, now more than ever.

John Gilmour is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. He is a former CSIS analyst in counterterrorism and currently serves as president of the Canadian Association for Security and Intelligence Studies Vancouver.