By Justin Bourque and Heather Exner-Pirot

November 14, 2024

The announcement of a billion-dollar-plus deal between Enbridge and 23 First Nations and Métis communities in September 2022 – with the Indigenous partners acquiring 11.57 per cent of the Athabasca pipeline system in Alberta – marked a milestone in the trend of Indigenous equity ownership in major energy assets.

While several such deals had been completed before, the size of the Athabasca transaction brought it attention beyond the usual corners of Indigenous-industry relations. This was big business. And since a lack of social licence has been an inhibitor to resource development in Canada, one more solution was revealed.

Indigenous equity ownership is not the only tool to earn Indigenous consent and support for energy and resource development. But it is a very good one, and it has become the cause célèbre for economic reconciliation.

In Alberta, the provincial government created an Indigenous loan guarantee program, called the Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation, which backed several large deals. Its success has inspired Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Manitoba, and the federal government to all announce similar programs over the past two years. In an economy with few bright spots, Indigenous equity in major projects is a source of optimism and praise.

To better understand the mechanics of Indigenous equity ownership, it’s important to consider the lessons learned from a series of deals negotiated between oil and gas companies and Indigenous communities between 2021–24 in Alberta. The deals demonstrate the unique characteristics of negotiations between large corporations on the one hand, and First Nations and Métis communities on the other, with both needing to demonstrate flexibility and accept new ways of doing things. While there are always challenges inherent in these negotiations, with enough good faith and humility, all sides can come out winners.

A new hope: Indigenous loan guarantee programs

For most of the 20th century, government and industry rarely considered the impacts of resource development on Indigenous rights. Indigenous nations suffered the environmental harms, but very rarely enjoyed any economic gains. This situation was deeply unjust.

In the 1980s, following the affirmation of Aboriginal rights in the 1982 Canadian Constitution, processes such as the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry, and development of Indigenous-owned Economic Development Corporations (EDCs), the tide began to turn. Many corporations sought to build good relations with their Indigenous neighbours through Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs), procurement, training and employment, and community donations. In return, they gained support – or at least, lack of opposition – for their projects.

Such corporate social responsibility went from being a “nice to do” to a “need to do” when the Supreme Court of Canada – in a series of decisions in 2004 and 2005 – affirmed the Crown’s duty to consult and accommodate First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities when approving activities that impact Aboriginal rights such as hunting, fishing, and gathering.

A decade of uncertainty, legal challenge, delay and capital flight followed, as new rules about how to fulfil this duty to consult were developed, implemented or rejected.

As the resource sector adopted IBAs as its main tool for negotiating Indigenous compensation, another idea began to percolate in the 2010s: offering equity to Indigenous partners to secure and demonstrate their support.

Ontario was an early adopter. It launched the Ontario Aboriginal Loan Guarantee program in 2009 to support its green energy goals, specifically funding Indigenous equity in transmission, solar, hydro, and wind energy projects. Transmission and renewable energy projects became prominent in early Indigenous equity ownership, with other deals transpiring in BC, Alberta and Manitoba.

The first big corporate deal in the oil and gas sector was the East Tank Farm deal between Suncor, a large oilsands company, and the Fort McKay and Mikisew Cree First Nations in 2017. It saw the nations obtain 49 per cent ownership, worth $503 million, in a highly productive asset. The parties completed the deal using a conventional bond/financing structure – earning a high return on investment – due to Suncor’s desire to build a strong relationship with the two nations and ensure all parties were invested in the success of Suncor’s oilsands operations.

Out of this came the seeds of a provincially backed Indigenous loan guarantee program: the Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation (AIOC). This was then Premier Jason Kenney’s answer to growing public opposition to new pipelines in Canada, epitomized in the colloquially termed “no more pipelines” bill C-69, later the Impact Assessment Act. Legally and philosophically, Canada and Canadians were much more likely to support major projects that had Indigenous ownership and support.

Kenney knew Indian Resource Council (IRC) President Stephen Buffalo well, from their mutual connection to the acclaimed College of Notre Dame in Wilcox, Saskatchewan (Kenney’s father, Martin, was its president from 1975 –1992). The IRC represented First Nations with oil and gas production on reserve, as well as other oil and gas economic interests, and was generally pro-development. Its raison d’être was to enhance the economic prosperity and self-determination of its members. The AIOC concept aligned well with the IRC mandate, and Buffalo became a board member and later chair.

The AIOC was officially launched in 2019, capitalized with a billion dollars from the Government of Alberta. Its establishment took about six months from concept to formation. It concluded its first deal in September 2020: a $93 million stake from six First Nations in the Cascade natural gas power plant, a greenfield project which went into service in 2024.

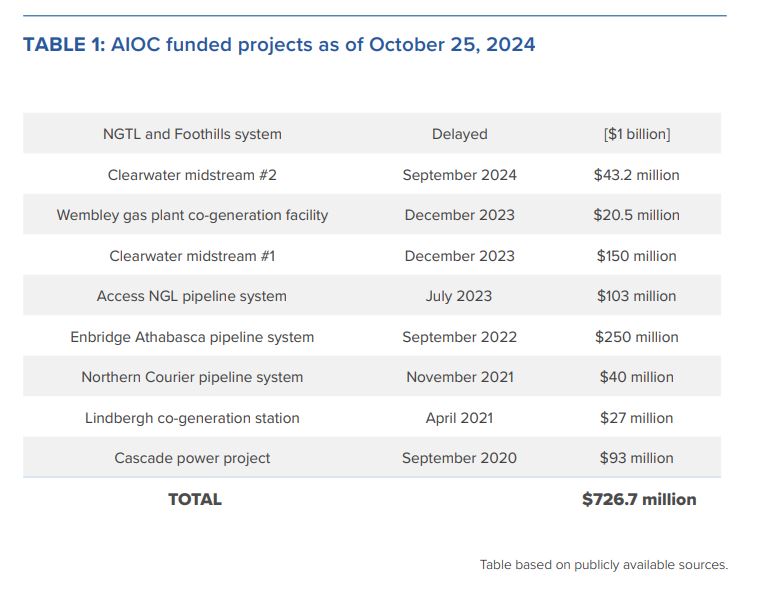

As of writing, eight deals have been concluded with loan guarantees totaling $727 million. The provincial government increased the amount able to be loaned to $3 billion in its fiscal year 2024–25.

The mandate of AIOC is narrow and its risk profile is conservative. Despite a high degree of interest from various proponents and nations, AIOC has guaranteed only midstream and generating infrastructure deals. AIOC has stated its desire to explore other industries, and its mandate includes “natural resources, agriculture, telecommunication, and transportation investments that will generate material sustainable revenues and benefits over the medium-to-long term for eligible Indigenous groups.” However, due to the favourable risk profile of the kinds of loans they are already executing, and the large deal flow evident in that space, it may be some time before we see deals concluded in other sectors, as these will require a different way of doing things.

While AIOC and the loan guarantee model have gotten the bulk of the attention, there are other models for Indigenous equity financing. In addition to the Suncor tank farm deal, Cedar LNG (the joint venture between the Haisla Nation and Pembina Pipeline Corporation that was the first and thus far only project approved under the auspices of the Impact Assessment Act) has been structured with conventional bond financing, although the Haisla did receive a $500 million loan from Export Development Canada. Several transmission line projects in Alberta, BC and Ontario have been financed without public loan guarantees, relying instead on the security of power purchase agreements. Some have been greenfield projects, while others have been a divestiture of ownership in existing assets. Some have involved a handful of nations, while others have involved dozens.

All of this is to say that while the AIOC loan guarantee for existing infrastructure has emerged, deservedly, as the most well-known type of Indigenous equity deal, it is far from the only model available.

AIOC pipeline deals: lessons learned

The Art of the Deal: Negotiating Indigenous Equity

Fundamentally, the Alberta Indigenous equity infrastructure deals are business transactions – they do not comprise nor discharge the Crown’s duty to consult, and they are not a negotiation nor a satisfaction of treaty obligations.

And yet, they are not traditional business transactions either. It is fair to say that these Indigenous equity deals represent a new type of business relationship that has required compromise and humility from both sides.

To start, these deals are highly complex due to the large number of parties. Most oil and gas deals of this kind (e.g. selling off midstream assets) are made between two CEOs; a deal involving three parties is considered complicated. In the case of the AIOC deals, there can be dozens of parties: the nations, the oil & gas company, AIOC and all of the various lenders.

Because there are more financial and legal advisors, there are also more fees. That makes the deals more expensive. A certain threshold, or minimum deal size, is necessary to be able to absorb those ancillary costs.

For their part, oil and gas companies have had to adapt to a negotiation that is less transactional than they’re used to. Negotiations with their peers or their customers are generally driven by the economics of the transaction: acquiring or divesting an asset and agreeing on the terms of a product or service.

With Indigenous partners, these agreements are seen much more from the lens of entering into a relationship. This implies a deeper and longer-term commitment. Is the corporation likely to be a good partner, or not? Can they be trusted in the nations’ traditional territory, not only today but in the future? A lack of trust and suspicion – likely based on decades of negative experiences – is likely to be present and must be overcome.

This impacts the style of the negotiation. Some Indigenous nations may come in hot, seeking acknowledgement or rectification of genuine historical grievances with the corporation or the industry. CEOs may be reluctant to discuss such topics, seeing them as outside the boundaries of their responsibility and the negotiation. They often believe they’re offering a good deal in good faith, and for their troubles getting run through the ringer.

Both sides benefit from a degree of openness that is not typically found in business negotiations. Both need to be willing to do things differently than has been done in the past.

Corporations need to understand how industry has traditionally viewed Indigenous people as a barrier to be overcome and appreciate the negative impacts this has had. These past relations and legacy issues can be honoured while creating a forward-looking relationship that seeks an alignment of interests. But they need to be acknowledged.

CEOs need to play an active role in these negotiations, including liaising with their First Nation Chiefs/Métis Settlement Chairpersons and/or Councillor counterparts. Others may do the leg work of negotiating and closing the deal, but having a “Chief-to-Chief” relationship and open line of communication is key.

Indigenous nations need to understand that they are not negotiating treaty or IBAs, and they are not entitled to a deal. They are negotiating a business agreement and need to approach it from that perspective. Out-of-market benefits should not be expected, lest the deal fail on economic grounds.

Commercially and behaviourally, they should approach the negotiation as a partner. If communities want to have a voice at the table, they need to take the time to be prepared and understand their role: as a business partner, not an adversary.

Finally, while nations and corporations may be getting better and more experienced, every deal will be unique and have its own historical and cultural context. Just because an approach is successful in one instance does not mean it will be successful in others. The business world trends towards a “rinse and repeat” model to achieve maximum efficiency. This is not likely to be the best strategy when dealing with new and diverse Indigenous nations.

Governance Structures

Thus far, pipeline equity deals in Alberta have been negotiated between the existing owner of the asset on the one hand, and a consortium of First Nations and Métis communities on the other. Because these are business deals, the Indigenous nations must organize together as a business entity; typically, a Limited Partnership (LP).

The LP must be set up from scratch and work through a host of governance decisions, including the number of directors and composition of the board. Should these be community representatives? Chiefs and councillors, economic development officers, or someone else? Some combination of community-appointed and professional directors? What are the term lengths? What decisions are they empowered to make, and what decisions require the approval of the shareholders (i.e. the other Indigenous partners?)

It is also essential that directors act in the best interests of the LP, not a particular community. In fact, this is a legal requirement of board directors, as part of their fiduciary duties. Confidential information held by board directors may not be shared with the First Nations and Métis councils. Conflicts of interest, real or perceived, may arise, and governance structures must be resilient to these.

For the corporate partner, having a business partner with strong governance is essential. It is not their role or right to determine how their Indigenous partners organize their affairs. But many deals are concluded quickly to avoid the uncertainty and risk that First Nation and Métis council elections (often conducted in two- or three-year cycles) add to negotiations.

Financing

The financing of major projects involves a “capital stack”: the combination of debt and equity used to purchase or build an asset. Equity owners are paid after lenders, and thus hold a riskier position. This is compensated by the higher expected return on investment.

The AIOC assumes the financial risk for Indigenous nations through its guaranteed loans. If the returns from the asset – in the case of pipelines, the tolls and tariffs – cannot cover the cost of debt, AIOC absorbs the default. As such, like most lenders, AIOC is conservative when deciding which projects it will or will not support. Of its five midstream deals, it has backed only assets already in service with long term contracts and/or take-or-pays, making them very low risk. As different sectors come into play, the economics and merchantability of various products will require the AIOC program to evolve.

This low-risk appetite often suits the Indigenous communities. Few have the equity available to enter into these deals without some kind of backing, and because almost all Indigenous communities have more community needs than money to meet them, there is often a wariness of entering into risky ventures.

While there is also the option of borrowing in capital markets, most Indigenous communities face high interest rates. The delta between the AIOC’s rate of borrowing (which is equivalent to that of the Province of Alberta) and that of Indigenous communities for equity capital is often 5 to 10 points, and the difference between a healthy rate of return and a negligible one.

That said, equity – Indigenous or not, guaranteed or not – still entails some risk. Equity returns are not payments, as they are with IBAs. The amount is not fixed, but rather is based on profits. As such, cash flow will vary. LP boards need to be mindful of that and manage the investment appropriately. Communities must budget accordingly.

Impact

The impact of the AIOC deals completed to date are often much more meaningful than a traditional business exchange. Fundamentally, they are about providing impacted Indigenous communities with a level of benefits from, and participation in, Alberta’s prolific oil and gas sector not previously enjoyed.

Communities use their revenues to fund their own priorities: an elders’ lodge, a hockey rink, even land. They can also use their revenue stream, and their portion of the asset once the debt has been sufficiently paid down, as security or collateral that allows them to borrow and invest in other assets and ventures.

Those corporations and nations involved in these deals, as well as their advisors, also develop new capacity and expertise that engenders subsequent deals. Having already entered into a partnership, the nation and corporation may go on to enter into different business deals, such as contracts for services, or equity partnerships in assets below the AIOC threshold.

Because they provide an opportunity for nations to address their own economic needs, they enhance their self-determination and become less reliant on government supports.

Another ripple effect of the AIOC deals is the capacity it has built in the financial and legal community. Big banks such as RBC, CIBC, and ATB, and firms such as MLT Aikins and MNP are getting better at advising on these deals, including the unique legal and cultural considerations Indigenous clients may have. That in turn is paving the way for more and better deals. As more deals are closed, the legal and financial advising side should become more efficient and the fee burden should be reduced.

Just as importantly, it is also building capacity and market for Indigenous financial and legal advisors and businesses, such as Åsokan Generational Development (which co-author Justin Bourque founded). The AIOC deals do not just support Indigenous revenue streams; they are building an ecosystem in which Indigenous professionals can compete and succeed. Those services are highly valuable. Someone needs to work with and align the communities and be trusted to do so. A skilled, Indigenous, professional is usually what is required to get the deal over the finish line.

Many investors and financial institutions are now piling into the space: an overall positive development. The establishment of the federal Indigenous loan guarantee program is anxiously awaited, as many deals wait in the wings for access to the Government of Canada’s rates of borrowing and $5 billion capitalization.

Finally, this model has improved the overall environment for industry and First Nations and Métis communities in the energy sector. Their interests are more aligned, because they do well when their partner does well.

It’s hard to quantify this benefit but moving from an era of fraught and adversarial industry-Indigenous relations, to one of mutual interest and partnership, is undeniably contributing to a reconciliation that benefits all Canadians. For this, the AIOC, nations, corporations, and advisers involved should be applauded.

Anatomy of a deal: the Clearwater midstream

Tamarack Valley Energy (TVE), a mid-sized exploration and production (E&P) corporation based in Calgary, began acquiring assets in the Clearwater heavy oil play in 2021. Its activities there impact the Aboriginal rights of thirteen First Nations and Métis communities in northern Alberta.

TVE subsequently sought to sell a proportion of its midstream assets in the region to1) develop a long term and mutually beneficial relationship with local Indigenous rightsholders by ensuring they earn a return commensurate with performance from TVE’s activities; and 2) recycle revenue from a low risk but low returning midstream asset into higher risk but higher-returning exploration and production activities, and pay down debt, in the face of high capital costs.

TVE offered fifteen nations an equity stake in its midstream assets, with no differentiation in share amounts for the respective First Nations and Métis partners. Twelve accepted, including three Métis Settlements and nine First Nations (Driftpile Cree Nation, Peavine Métis Settlement, Duncan’s First Nation, Peerless Trout First Nation, East Prairie Métis Settlement, Sawridge First Nation, Gift Lake Métis Settlement, Sucker Creek First Nation, Kapawe’no First Nation, Swan River First Nation, Loon River First Nation, and Whitefish Lake First Nation #459). The twelve nations entered into the Wapiscanis Waseskwan Nipiy Holding Limited Partnership (WWN).

On December 13, 2023, the deal was announced. WWN acquired an 85 per cent non-operated working interest in the newly formed Clearwater Infrastructure Limited Partnership (CIP) and Tamarack transferred $172.0 million of certain Clearwater midstream assets to the CIP for total consideration consisting of $146.2 million in cash and a 15 per cent operated working interest. Tamarack continues to be the operator of these assets. AIOC provided a loan guarantee of $150 million to WWN to support the deal. Revenues started to accrue to the WWN shareholders soon after closing.

Some time later, Bigstone Cree Nation requested entry into the WWN. Because its entry would reduce the share and revenues of the other twelve members, another deal was struck to expand the deal. On September 17, 2024, Tamarack transferred an additional $50.8 million of certain Clearwater midstream assets into the CIP for cash consideration of $43.2 million (before closing adjustments) while maintaining a 15 per cent operated working interest in the CIP. AIOC supported the expansion with a $43.2 million loan guarantee.

As Bigstone Cree Nation Chief Andy Alook said, “the support and alliance with AIOC is the epitome of financial transactions that puts First Nations and the Industry on the path toward improved relationships. We continue to support our nation in economic opportunities while enhancing the relationships we develop along the way.”

About the Authors

Justin Bourque is the Founder of Âsokan Generational Developments and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Heather Exner-Pirot is the director of Energy, Natural Resources, and Environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.