This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Heather Exner-Pirot, February 6, 2026

Carney promised to turn Canada into an energy superpower during the 2025 election, and I’m starting to believe he meant it. On top of the Alberta-Canada MOU, Carney has talked up our oil and gas sectors in his travels abroad. Crude oil looks likely to form the foundation of new trade deals with China and India, and new LNG projects will serve Japan, Korea, and other allies.

Carney reiterated this strategy in his excellent speech in Davos, saying that “Canada has what the world wants. We are an energy superpower,” and we are “fast tracking a trillion dollars of investments in energy, AI, critical minerals, new trade corridors, and beyond.” His international reputation now rides on fulfilling this promise.

I genuinely appreciate the change in tone from what was endured for 10 years under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. But the gap between what is being said and what is being done by the Carney government on energy is getting too big to ignore. The pancake stack of investment-killing climate regulations introduced by former ministers of environment Catherine McKenna, Jonathan Wilkinson, and Steven Guilbeault is not only largely intact; additional phases of their legacy policies are kicking in, and new ones are being added by Carney.

The noose is tightening, not loosening.

Any success our energy sector is having in this geopolitical moment is largely despite, not because of, Ottawa. To approach anything resembling energy superpower status, Canada’s federal climate policy structure must undergo a rupture, not a transition, from the past.

What climate policies are killing our competitiveness? Let me count the ways.

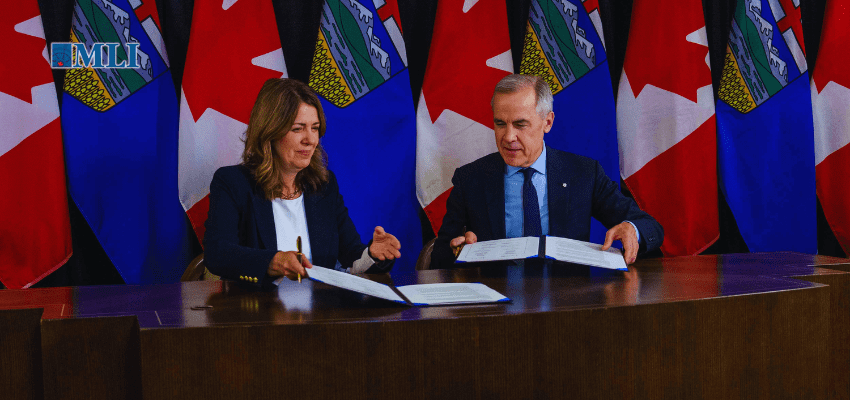

The usual suspects are Danielle Smith’s “Nine Bad Laws,” which were ostensibly addressed by the November MOU. For companies wanting to make investments, the MOU is not yet factoring into their decision-making because they still exist as commitments, not changes, to the regulatory environment, and too many unknowns remain.

While the much-hated greenwashing provisions in the Competition Act are likely to be amended in the budget bill, the government announced in December that it was still moving ahead with a “green taxonomy” or sustainable development investment guidelines to reach net-zero targets.

Inexplicably, it selected the Canadian Climate Institute, an environmental group established by the Trudeau government, to lead it. That has raised hackles across the energy sector, many of whom view the Institute’s past work as radical or ideological.

Alberta’s carve-out from the Clean Electricity Regulations, intended to unleash data centre investment and build new electricity generation, depends on a successful agreement on industrial carbon pricing by April 1. Optimism that this can be done was shattered when Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) put out a new discussion paper on changing the industrial carbon pricing system on December 19th: a classic ECCC Christmas present.

The discussion paper outlines a series of options to help it “strengthen” the federal benchmark, or carbon price, which the MOU identifies as $130/tonne. Currently, emitters for both output-based pricing systems like Alberta’s TIER program and the Quebec cap-and-trade system pay an actual carbon market price far below that “headline” benchmark, generally landing in the $20-$55 range. The discussion paper aims to create a system where the carbon price is “close to the minimum national carbon price, with some level of discount due to transaction cost of buying and selling credits.”

In other words, it will be a carbon tax, not a free carbon market, and it will be manipulated to reach as close to $130 as possible. This comes after the MOU committed to “recognize Alberta’s jurisdiction over TIER.”

Industry has been asking for greater certainty in the industrial carbon pricing schemes. The general reaction to this most recent ECCC volley is that it will provide certain death. At an approximately $130/tonne carbon tax, there will be no new production of oil to fill a new pipeline, no new natural gas-fired electricity to power data centres, no new critical mineral smelting facilities to secure our supply chains. Rather, there will be capital flight.

But wait, there’s more.

ECCC finalized its Methane Regulations in December in order to reduce oil and gas methane by 72 percent below 2012 levels by 2030. The MOU in November committed to a methane equivalency agreement with a 2035 target date and a 75 percent reduction target relative to 2014 emission levels. While ECCC has estimated compliance costs for the regulations at $48/tonne, the Canadian Gas Association has said field testing and real-world data indicate compliance would cost an average of $3,000/tonne.

This reflects a common complaint about ECCC models and assumptions: they rely on industry adopting technologies that do not yet exist. These leaps of faith do not comply with the federal government’s own guidelines for costing, which require models that are credible, reasonable, and replicable.

This is just what has been done by the Carney government since the MOU was signed. But there is another layer of regulation entering force: policies developed under Trudeau with phased implementation periods, updates, or reviews.

The 2025 edition of Canada’s National Model Codes, for example, introduces mandatory, measurable, and increasingly stringent requirements to limit emissions in new buildings. It implicitly reduces or eliminates the ability of builders and homeowners to choose natural gas-based heating systems, thus pushing them to use electric options instead. This comes at the same time as the Clean Electricity Regulations have limited options for new dispatchable generation, the reserve capacity of many Canadian electricity utilities is under strain, and electricity rates are rising.

Finally, while the Clean Fuel Regulations were only enacted in 2023, the government is already pursuing targeted amendments to compensate for some of its design flaws, namely the inability of Canadian biofuel producers to compete with cheaper imports.

The consequence is that Canada is now reliant on foreign suppliers to provide its mandatory low-carbon fuels, and the government is proposing domestic fuel quotas. Many in industry believe the changes proposed will make a complicated, rigid, and bureaucratic system even more so, with the costs inevitably passed on to fuel consumers in Canada.

To be fair, Carney has paused or cancelled a number of Trudeau-era policies as well.

This regulatory purgatory is hardly ideal. The federal government’s constant proposing, implementing, and then pulling back of unworkable climate regulations continues to be a huge drag on Canada’s energy sector and on this country’s productivity. It wastes scarce time and resources when we unquestionably have more important things to do.

For Canada to really become an energy superpower—to meet our full potential—Carney must find a way to unwind the labyrinth of climate policies that his predecessor brought about and replace it with a system that is pragmatic, achievable, and predictable.

Taking years to do so, not changing anything at all, or doing it to rather than with Canadian industry will not meet the high bar that Carney set for himself, and for us, in Davos.

Heather Exner-Pirot is the director of energy, natural resources and environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.