This article originally appeared in the Edmonton Journal.

By Dan Pujdak, December 18, 2024

Canada’s new Arctic foreign policy sends a loud message to the world: Ottawa is unaware of its own shortcomings and unready for the realpolitik of the modern age.

In yet another dense policy document, Canada is maintaining a static response to rapidly evolving global events without a strong vision of what Canada wants to be as an Arctic state or clear commitments about what we might do to get there.

The new foreign policy, revealed Dec. 6, by Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly, is primarily a reaction to an Arctic changed by Russian aggression. In fact, three of the five strategic challenges are directly related to Russia, with lesser references to China.

It’s important to realize geopolitical realities; it’s simply too bad it took this long.

It doesn’t respond to some of our most pressing challenges: the changing nature of our relationship with the United States or our NATO allies, the lack of domestic capital investment into critical minerals and infrastructure, which has left a vacancy our rivals would love to fill, or the ongoing collapse of the rules-based global order.

Perhaps the failure to recognize Canada’s challenges is why the policy feels so divorced from reality. After all, who can do anything but laugh when reading that Global Affairs believes “Canada engages in the Arctic from a position in strength, in part due to the CAF’s presence and capabilities, exercises, and operations … .”

This is, of course, the same military force whose only naval refuelling station in the Arctic cannot be used in the winter.

Canada’s response to new Arctic threats rests on three basic assumptions: strong Arctic communities add to northern security; improved intelligence, military readiness and alliances supporting both are essential; and diplomacy will reinforce Arctic sovereignty and disputed maritime claims.

These aren’t controversial or necessarily wrong ideas, but what’s strange is Ottawa seems to believe these assumptions are givens.

It’s bizarre that Ottawa seems to believe northern communities are well integrated into the rest of Canada (they aren’t), that our military is prepared for the North (it isn’t), that we can rely on our NATO partners when we fail to meet our military spending commitments (we can’t), that old multilateral forums will continue to create diplomatic pathways for us (they won’t), and that the post-Cold War rules-based order will triumph (it might not).

If these assumptions are conditions for Canada’s success and sovereignty, we had better get to work to make them workable. That would take historic levels of investment that Ottawa has never seemed interested in making.

Unfortunately, the policy doesn’t recognize how far the Arctic world has shifted and as a result is filled with contradictions and non-starters. It believes the Arctic Council is a worthy investment and Canada’s future term as chair can help us with diplomacy. But given the council’s current challenges, Canada may be better off creating or investing in alternative institutions.

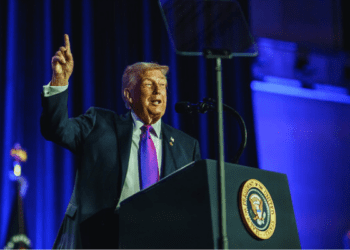

It believes we can negotiate an end to offshore Arctic claim disputes with the United States — a challenging prospect with president-elect Donald Trump, who is none too pleased with Canada’s lax approach to military security and unlikely to be willing to cede geopolitically strategic and energy-rich American Arctic maritime claims.

The policy pushes back against non-Arctic states asserting themselves in the Arctic but invites several of our non-Arctic allies as partners at the Arctic table, seemingly challenging the principle of Arctic primacy.

The policy doesn’t seem focused on attracting friendly capital investment in Canada’s Arctic — particularly the development of critical minerals — or trade, which are missed opportunities and likely our most important value proposition to allies.

Perhaps the only bright spots are that the policy rightly acknowledges that Indigenous communities must be involved as leaders in Arctic foreign policy — a well-accepted idea — and that we will be opening consulates in Alaska and Greenland.

Based on Ottawa’s inability to make critical Arctic and military investments to date, it’s difficult to give benefit of the doubt that this policy will be the basis for an improved approach to Arctic sovereignty.

One can hope the policy’s lack of grounding in modern reality is because of a heightened ambition to create a better world, but it’s more likely a reflection of Ottawa’s unawareness about the world we live in.

Dan Pujdak is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and chief strategy officer at Blackbird Strategies. He previously served as the director of policy to the minister of Crown-Indigenous relations and Northern Affairs Canada.