If Canada is serious about improving its defence procurement system, it requires a comprehensive set of reforms that addresses multiple issues simultaneously. There is no silver bullet that will solve the majority of the problems, writes Richard Shimooka.

If Canada is serious about improving its defence procurement system, it requires a comprehensive set of reforms that addresses multiple issues simultaneously. There is no silver bullet that will solve the majority of the problems, writes Richard Shimooka.

By Richard Shimooka, January 21, 2019

Canada has experienced a disappointing history with defence procurements, dating as far back as Confederation (and even before). Canadians may be inclined to take comfort that, while their country’s defence procurement history has been such a disappointment, it is unremarkable when compared to other western countries. However, a closer of examination of the history shows that Canada has an exceptionally ineffective system, especially for major capabilities purchases.

Arguably the country with the closest record to Canada is the United Kingdom. It has faced a string of high-profile challenges and failures. The most notable was the 2011 cancellation of the BAE Systems Nimrod MRA4: a troubled maritime patrol plane that was axed after £3.4 billion dollars was spent on the program. Another example is the Type 45 destroyer, which was approximately 30 percent over budget and fraught with technical problems. Many Canadians are more familiar with the United States and its well publicized troubles, like the F-35 program or Zumwalt-class destroyer, where overruns can run into tens of billions of dollars.

Against such a record, one might assume that Canada has not faired altogether badly relative to others. What these comparisons fail to grasp is that most of these foreign failures are developmental projects, which are fundamentally complex, risky and prone to failure. They usually involve identifying and maturing new technologies, then incorporating them into a new capability.

By comparison, the vast majority of Canada’s military procurements involve what is known as “off the shelf” purchases. This means the government selects from an existing capability that may be in or near entering service. Such programs should be straightforward, as all of the risks involved in technological development are resolved. Nevertheless, Canada frequently is unable to execute even this basic level of competence.

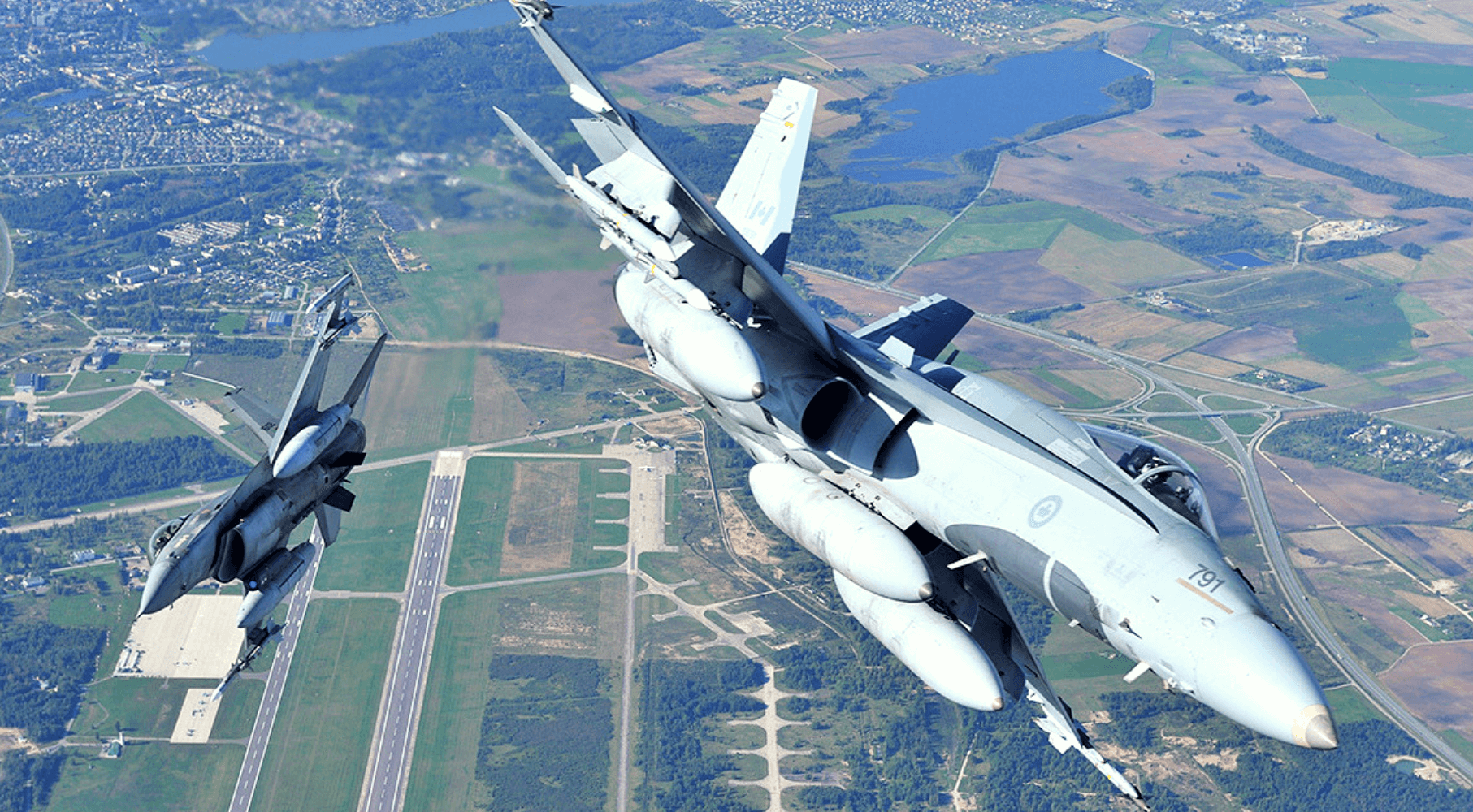

The Canadian Surface Combatant program to replace the Halifax frigates is a good example. The government purchased an off the shelf design—the BAE systems Type 26 frigate—to avoid much of the initial development work. Nevertheless, the project program costs nearly doubled from the early estimates of $14-billion to $30-billion, at a cost that rivaled a clean-sheet development program. Similarly, Canada’s fighter replacement program will have gone over for 16 years under the present government’s timeline. Most countries required only two to four years to select the F-35 (if they ran a competition at all).

The causes of Canada’s problems are manifold, with few obvious fixes. Political actors bear a significant burden of responsibility, often pursuing policies that have been detrimental to the procurement file. As several commentators note, there are few political benefits in defence expenditure, except when it can be tied to specific constituencies. Program funding is frequently delayed or curtailed, or affected by political decision-making with adverse consequences.

Bureaucratic actors shoulder some of the blame as well, having created a byzantine structure for procurements. Since 2012, Public Services and Procurement Canada has assumed responsibility for the overall control and management of major defence procurements. This has introduced a crushing burden of bureaucratic structures that added a superficial ability to provide knowledgeable project management decisions. In addition, many non-military members are more interested in raising their organizational concerns than actual deliverables. Prior to 2012, sole souring was a valid technique that has nearly disappeared in the years since despite its utility. The reality is that the international defence industrial base has witnessed massive consolidation. Despite there being only one realistic supplier for many capabilities, the overriding preference has been to run competitions, increasing program costs and delaying capability delivery.

A military program manager may have as many as a half dozen oversight bodies and committees to report to, which eliminates his or her authority and adds unnecessary complexity to the process. The United States faced similar challenges, and has recently introduced reforms that have narrowed accountability. These have placed as much authority in the hands of a program manager as possible in order to promote effective management of projects.

If Canada is serious about improving its defence procurement system, it requires a comprehensive set of reforms that addresses multiple issues simultaneously. There is no silver bullet that will solve the majority of the problems. Foreign allies may provide useful lessons for Canada, which can learn from their hard-fought lessons. Otherwise the government will continue its disappointing track record of procurement outcomes, with the Canadian public and the military bearing the consequences.

Richard Shimooka is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Centre for Advancing Canada’s Interests Abroad.