THE CANADA AT A CROSSROADS SERIES

Canada is at a crossroads. The issues confronting Canada in 2025 go beyond mere setbacks and can more accurately be called crises. Unless they are resolved quickly, we face a deep and potentially permanent loss of our national standard of living and quality of life.

We hereby introduce the “Canada at the Crossroads” series of reports from the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Each one is a relatively short essay explaining the problem at hand and outlining potential solutions. This series will not propose minor tweaks to existing strategies, nor will it look only for modest course corrections. Canada is beset by incompetent governance, runaway and rampant ideology, social malaise, and a national identity crisis.

Its future is at stake – and the time for small, hesitant steps has passed. It is in this spirit that we invite readers to join us as we confront the problems facing our country and set out serious, disruptive ideas to make 2025 the year Canada began to step back from the brink.

VOLUME 4: CAPITAL IDEAS – ATTRACTING INVESTMENT, BOOSTING PRODUCTIVITY

By Ross McKitrick

April 10, 2025

Since 2015 Canada has been facing significant problems that include declining investment, dropping productivity, and falling real incomes. These are interconnected problems. Many analysts have cautioned that as real investment declines, so does productivity, and ultimately so does real income (see, for instance, Bafale and Robson 2024, Globerman 2024, Tombe 2024, Sharpe and Sargent 2023). Many metrics reveal the scale of the problem. Consider, for instance:

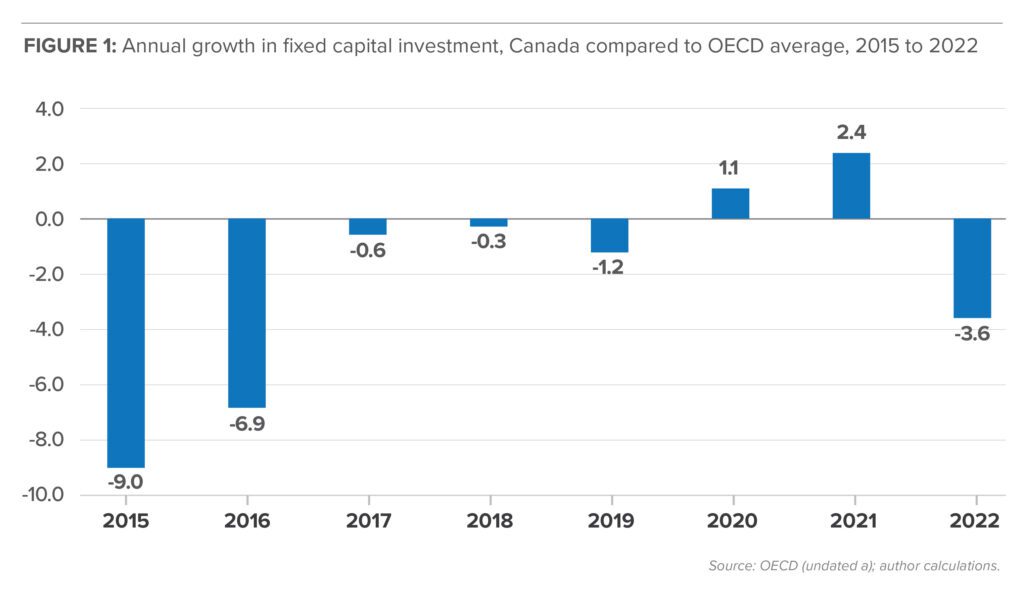

- In the US, and for the OECD as a whole, fixed capital investment grew every year from 2015 to 2022 except for 2020. But fixed capital investment in Canada declined in four of those eight years (2015, 2016, 2020, and 2022) and in six of those years the rate of change was below the OECD average (Figure 1).

- Canadian workers now have access to about 55 per cent of the capital per worker available to their US counterparts, and about 70 per cent of that of the average OECD worker (Bafale and Robson 2024).

- The capital formation that does take place in Canada is heavily biased towards buildings rather than equipment, information technology, or intellectual property (Globerman 2024). In 2022, 38 per cent of Canada’s gross fixed capital formation was directed towards housing, the highest fraction in the OECD. Germany was second at 33 per cent while all other countries devoted less than 30 per cent of capital investment to housing (OECD undated b).

- Business sector output per hour grew by 1.8 per cent annually in the United States from 2000 to 2022 but by only 0.9 per cent – half as much – annually in Canada (Sharpe and Sargent 2023). From 2019 to 2022 business sector output grew by 1.6 per cent annually in the US and only 0.2 per cent annually – one eighth as much – in Canada.

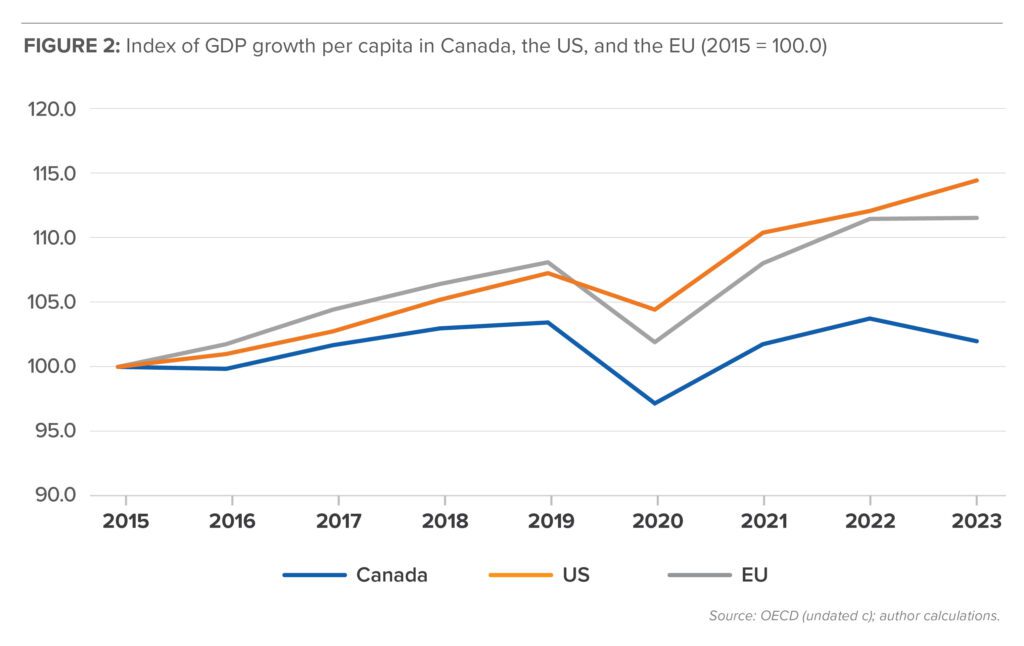

The lack of capital investment means that Canadian workers produce relatively less per hour than their counterparts in other countries, which leads to stagnant overall productivity and thus to stagnating real incomes (Sharpe and Sargent 2023). Figure 2 shows real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in Canada, the US, and the European Union, indexed so that each country begins at 100.0 in 2015. Canada’s GDP per capita grew by only 2.0 per cent over nine years overall, compared to 11.5 per cent in the EU and 14.4 per cent in the US.

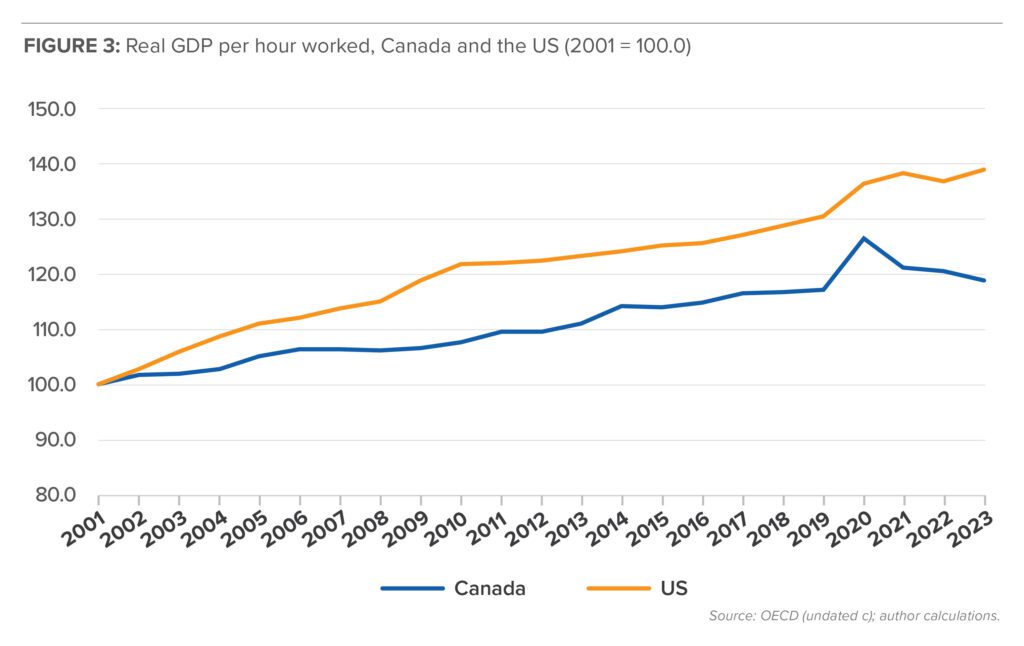

The productivity and income gap did not begin in 2015. Figure 3 shows GDP per hour worked in Canada and the US beginning in 2001. The gap opened in the first decade of this century although it did not widen in the second decade. But since 2020 the lines have diverged with Canada’s now declining in absolute terms.

There is a direct relationship between productivity and real income. While national GDP can be boosted by population growth, if output grows more slowly than the population, average real income goes down. Increasing per capita income requires each worker to produce more. In most cases this requires investment in better equipment, better information technology, more knowledge, and so forth. But these are the kinds of investments that Canadian businesses are not making at rates consistent with counterparts in other countries.

We need to ask why the Canadian and international business communities have decided that Canada is not a preferred place to invest. The declining relative and absolute rates of investment per worker threaten to create a doom loop if not reversed:

- Declining investment leads to declining income per capita.

- The burden of maintaining high levels of public spending and the government’s misguided desire to replace declining private investment with government-directed investment leads to upward pressure on tax rates.

- Increased taxes and government control of economic activity drive away even more private investment.

- The declining standard of living leads to an exodus of highly skilled workers and the further deterioration of Canada’s growth prospects.

The end result of this downward spiral will be a permanently lower standard of living. To avoid this outcome, we need to enact significant public policy reforms that make Canada a popular place for private-sector investment, specifically in productivity-enhancing equipment, technology, and intellectual capital. The answer to Canada’s productivity problem is not for the government to give money to corporations in an attempt to “pick winners,” but for the government to create conditions in which the private sector will want to invest in Canada.

Some preliminary principles

An action plan will be set out below that contains specific policy suggestions for restoring investment and growth to the Canadian economy. But first, we note four preliminary principles:

- Government should stop using the word “investment” as a euphemism for spending. Government spending is only investment when it is directed towards capital assets that earn market rates of return, but in most cases if the investment had the prospect of earning such a return the private sector would have done it already. Otherwise, spending is spending and should be called such.

- Cease government-led corporate welfare schemes in which billions of dollars are sunk into money-losing enterprises that the private sector refuses to support. The latest large-scale example is Electric Vehicle (EV) battery plants in Ontario, but other examples abound.

- Recognize the importance of rewarding entrepreneurs. Even in Canada’s relatively risk-averse investment climate, people will put up capital to support a venture that is potentially profitable as long as they have a reasonable expectation of keeping most of the profits. Otherwise, they will undertake the investment in the United States or elsewhere. Canada’s high top marginal personal income tax rates are a deterrent to domestic entrepreneurship.

- Refocus immigration to bring in people with the skills and capabilities to earn above-average incomes over their lifetimes so they don’t drag average incomes down.

Action Plan

Personal income tax reforms

A separate volume in this series discusses personal tax reform in some depth. However, it is important to mention that in most income categories Canada has the highest personal income tax rates in North America. This is especially true for high-income earners, which means successful business owners will be strongly predisposed not to build their operations north of the border, in part to protect their own wealth, but also because the high-value talent on which they rely will be harder to attract and retain. Our taxes are high even for low-income households and the burden needs to be reduced across the board. But for the purpose of promoting our long-run productivity growth there is no avoiding the need to make Canada an attractive place to live for high-earning entrepreneurs and investors who make and direct business investment decisions.

It is difficult to understand why someone on track to develop a successful capital-intensive company will choose to do so in Canada if they have the option of going to the United States. Both the owner/entrepreneur and all of his or her highest-value employees would face marginal income tax rates at or above 50 per cent in Canada versus a top marginal income tax rate typically around 40 per cent in the US. Even if the business owner was personally willing to incur the higher tax costs in Canada, he or she would realize that attracting and retaining top talent is an uphill battle if the company is located here.

A “big bang” corporate income tax reform

Taxing corporate profits through a corporate income tax (CIT) is something of a puzzle in economics. Governments raise revenue by taxing income. In principle it should not matter whether the income is derived from labour or ownership of capital. If corporations pay taxes on their profits, and shareholders also pay taxes on investment income, capital potentially faces double taxation. The system of dividend tax credits is designed to make the tax treatment of dividends symmetric to that of wages.

Here is an example to explain why. Suppose a company earns $100 in profits. Suppose also that it pays a 25 per cent profits tax, so it has $75 left to give its shareholder. If the shareholder’s income tax rate is 50 per cent, he pays $37.50 on the dividends. But then the total tax burden on the profits was $62.50, or 62.5 per cent. Having a higher effective tax rate on corporate profits creates an incentive for companies to pay out all their earnings as wages or other expenses and return as little as possible to shareholders as dividends. If not fixed, this imbalance would drive investment out of the country entirely. To avoid this, Canada’s tax system adjusts dividend tax rates so the overall tax burden on corporate profits is the same as if they were wages. In this example, that would entail taxing dividends at two-thirds of the ordinary income tax rate (33.3 per cent rather than 50 per cent) which would imply the tax on $75 of dividends is $25, bringing the total tax bill for capital income to $50, the same as if it was paid as wage income.

The corporate tax base is unusually sensitive to changes in the CIT rate, and this sensitivity can be exploited to reduce the net cost to government of cutting corporate taxes. Economists refer to the percentage change in the size of a tax base with respect to a one per cent increase in the tax rate as the tax base elasticity. Dahlby and Ferede (2018) estimate that long-run CIT base elasticities range from -6.1 to -17.6 across Canadian provinces, which they find to be much higher than the base elasticities of income and sales taxes. This means that in response to even small changes in CIT tax rates companies undertake large adjustments in their domestic activities. The CIT base elasticities are high enough that in some provinces a reduction in the CIT rate would trigger a large enough increase in the corporate tax base as to increase total government revenue.

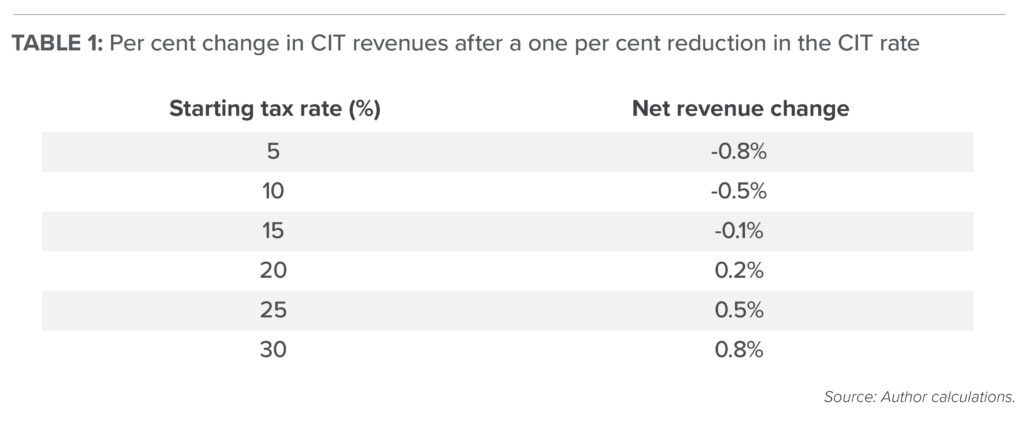

Table 1 shows the effect on CIT revenues were a government to cut CIT rates by one per cent when the base elasticity is -6.1. If the initial CIT rate is 5 per cent and is adjusted down to 4 per cent, government revenue would decline by only 0.8 per cent. The higher the starting tax rate the smaller the proportionate loss of revenue. At a tax rate of between 15 and 20 per cent a reduction by one percentage point causes enough of an increase in the CIT base that the tax change ends up being revenue neutral. If the starting rate is 25 per cent, which corresponds to the average CIT rate across Canada (Tombe 2024), reducing it to 24 per cent would increase total CIT earnings by about 0.5 per cent; in other words, by reducing the CIT rate the government would end up collecting more tax revenue than before.

We might then ask, why not get rid of the tax on corporate income altogether and just tax profits when they are paid out as dividends to shareholders, at the shareholder’s marginal income tax rate? There is real-world precedent for this experiment. According to Mintz (2022) in 2000 Estonia changed to a distributed tax model in which corporate profits are taxable only when distributed to investors, and the tax rate was set equal to the income tax rate. Latvia did the same in 2018. This effectively removed the tax on reinvested profits, making Estonia a very attractive place for investment. Mintz states that, rather than leading to a drop in government revenue, since 1999 Estonian tax revenues from corporate income increased fivefold and rose from 0.9 per cent of GDP in 1999 to 1.7 per cent of GDP in 2019.

Mintz calls this a “big bang” corporate tax reform: taxing corporate profits only at the point where they are paid out as dividends to shareholders, at their pre-existing income tax rate. His analysis identifies some modifications that would be necessary to make the plan truly neutral, such as provisions to deal with share buybacks and certain payments that would need to be treated as deemed dividends.

The biggest effect of this reform would be to make the reinvestment of corporate profits tax exempt. Companies that used retained earnings to pay for fixed capital formation, rather than paying for it through equity or debt financing, would only pay taxes on the investment at the point when the investment yielded dividend earnings in the future. This would provide a substantial boost to investment incentives in Canada. The Mintz proposal ends up being nearly revenue neutral even without taking account of the tax base elasticity effect, and in the long run would thus likely lead to an increase in corporate tax revenues even while providing a significant improvement in incentives for domestic fixed capital formation.

A “big bang” regulatory repeal

In addition to the “big bang” corporate income tax reform proposal, Canada needs a “big bang” regulatory rollback to reverse much of the anti-growth agenda enacted by the Trudeau government since 2016, and even more importantly cancellation of the planned new regulations to begin in 2026 under the federal Emission Reduction Plan (ERP). The rules fill more than 200 pages in the 2023 edition of the ERP and cover every aspect of the economy (Canada 2024). While the carbon tax is costly enough (less so now with the consumer charge removed), the regulatory agenda is far costlier (McKitrick 2024) and its rollback is thus of far greater priority.

One hurdle to repeal is that past regulations were supported by Regulatory Impact Assessments (RIAs) that ostensibly showed they generated more benefits than costs. However, many RIAs employ flawed assumptions about consumer irrationality. The most common examples are related to energy efficiency requirements, where bureaucrats argue that by prohibiting certain consumer choices they make consumers better off. Suppose, for example, that consumers currently have the choice between two microwave oven models where one uses 20 per cent more power than the other and thus costs $75 more annually to run. The $75 is not a loss to the households who purchased the more powerful unit; it measures the benefits for which consumers are willing to pay to enjoy faster cooking times. Banning the unit would destroy part of the consumer surplus, yet in typical regulatory cost-benefit analysis the $75 would be treated as a “savings” (specifically because it corrects consumer irrationality) and it would be included as a benefit of the rule. Properly defining such measures as regulatory costs rather than benefits would destroy the case for many of the most expensive energy-related regulations of the past few decades in the US (Gayer and Viscusi 2013) and likely Canada as well.

Put another way, if banning high-power appliances is a savings, and thus a benefit for consumers, then we could “save” consumers even more money by banning appliances altogether. But it would obviously not make consumers happier – they are willing to pay for the energy needed to use appliances because the services of the appliances are valuable to them. The cost of running an appliance is a measure of the benefits, not costs, of the unit.

Adding to the imperative of deregulation is the sweeping set of Executive Orders (EOs) issued by the new Trump administration on its first day, and the new requirement that before any new regulations are imposed the bureaucracy must identify 10 for repeal (Villagran 2025). The EOs were especially aimed at removing barriers to energy development including fossil fuel extraction and processing and construction of new electricity generation facilities. While some elements of the repeal have yet to be litigated, the direction is clear and the contrast for investors when comparing Canada’s trajectory to that in the US will likewise be clear.

A more detailed treatment of priorities for deregulation will be presented in the cost of living volume in this series.

Potential challenges to implementation

The government should prepare to deal with criticisms of tax and spending cuts by explaining them carefully and implementing the cuts early (preferably within the first 6 months of taking office) so that the negative economic effects will be felt quickly and the effects of the compensating tax cuts will have had time to propagate through the economy before the lead-up to the next election.

Regulatory repeals will require revisions to Regulatory Impact Statements. In order to minimize the possibility of legal challenges it will be necessary not to simply issue new RIAs with what will appear to be arbitrary changes, but to publish careful critiques of previous RIAs and the methods used in them. This will also help serve to create guidelines for future RIAs.

The government should also examine the potential for expedited action on regulatory repeal, which would take the form of suspending enforcement of existing regulations while the full repeals are underway. In this regard it might be helpful for the government to override existing regulations by declaring a “cost of living emergency,” and under that rubric suspending enforcement of a set of regulations believed to be particularly costly for households.

Conclusion

Declining fixed capital investment is a silent killer for Canada’s standard of living. Critics instantly declared President Donald Trump’s tariff proposals against Canadian products to be a threat to the economy, but there has been no comparable outcry against the conditions that led to a 15 per cent relative drop in our per-capita income relative to the US since 2015. Nor has there been a comparable outcry against the policies that drove investment down such that Canadian workers now have just over half the capital available to them on a per-worker basis compared to their US counterparts. The Canadian government needs to enact major reforms to the ways corporations are taxed and regulated in order to attract new capital investment and begin rebuilding our national productivity.

About the author

Ross McKitrick holds a PhD in economics from the University of British Columbia (1996) and is a professor of economics at the University of Guelph in Guelph, Ontario. He is the author of Economic Analysis of Environmental Policy (University of Toronto Press 2010). He has been actively studying climate change, climate policy, and environmental economics since the mid-1990s. He built and published one of the first national-scale Computable General Equilibrium models for analyzing the effect of carbon taxes on the Canadian economy in the 1990s. His academic publications have appeared in many top journals. He has also written policy analyses for the Fraser Institute (where he is a senior fellow), the CD Howe Institute, the University of Calgary School of Public Policy, and other Canadian and international think-tanks. In addition to his economics research his background in applied statistics has led him to collaborative work across a wide range of topics in the physical sciences including paleoclimate reconstruction, malaria transmission, surface temperature measurement, and climate model evaluation.

References

Bafale, Mawakina, and William B.P. Robson. 2024. Underequipped: How Weak Capital Investment Hurts Canadian Prosperity and What to Do about It. Commentary No. 666. CD Howe Institute. Available at https://cdhowe.org/publication/underequipped-how-weak-capital-investment-hurts-canadian-prosperity-and-what/.

Canada. 2024. “2030 Emissions Reduction Plan: Clean Air, Strong Economy.” Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/climate-plan-overview/emissions-reduction-2030.html.

Dahlby, Bev, and Ergete Ferede. 2018 “The Marginal Cost of Public Funds and the Laffer Curve: Evidence from the Canadian Provinces.” Finanz – Archiv: Zeitschrift für das Gesamte Finanzwesen 74, 2: 173–99. Available at DOI:10.1628/fa-2018-0005.

Gayer, T. and K. Viscusi (2013). Overriding Consumer Preferences with Energy Regulations. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 43: 248–264.

Globerman, Steven. 2024. Comparing the Investment Performances of Canada and the United States over the Past Five Decades. Vancouver: Fraser Institute, July 2024 https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/comparing-investment-performances-canada-and-united-states-over-past-five-decades

McKitrick, Ross R. 2024. The Economic Impact and GHG Effects of the Federal Government’s Emissions Reduction Plan through 2030. Fraser Institute, July 18, 2024. Available at https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-impact-and-ghg-effects-federal-governments-emissions-reduction-plan-through-2030.

Mintz, Jack. 2022. A Proposal for a “Big Bang” Corporate Tax Reform. Paper 15:7. University of Calgary, School of Public Policy Research. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4037728.

OECD. Undated a. “Gross Fixed Capital Formation Investment” Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Available at https://data-explorer.oecd.org.

OECD. Undated b. “Investment by Asset: Dwellings.” Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Available at https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/investment-by-asset.html?oecdcontrol-c0d5ac5e97-var6=DWELLING.

OECD. Undated c. “Productivity Growth Rates.” Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Available at https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?lc=en&ac=false&tm=DF_PDB_GR&pg=0&snb=1&vw=tb&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_PDB%40DF_PDB_GR&df[ag]=OECD.SDD.TPS&df[vs]=&pd=2001%2C2023&dq=CAN%2BUSA%2BEU27_2020.A.KY%2BGDPPOP%2BGDPHRS……&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false .

Sharpe, Andrew, and Tim Sargent. 2023. “The Canadian Productivity Landscape: An Overview.” Canadian Tax Journal 71, 4: 1125–47. Available at https://doi.org/10.32721/ctj.2023.71.4.fon

Tombe, Trevor. 2024. Boosting Canada’s Competitiveness by Reforming Business Taxation. Fraser Institute. Available at https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/boosting-canadas-competitiveness-by-reforming-business-taxation.

Villagran, Lauren. 2025. “For Every New Rule, Trump Tells Federal Agencies to Eliminate 10 Old Ones.” USA Today, January 31, 2025. Available at https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2025/01/31/trump-reduces-government-regulation-10-to-1/78103293007/.