[Ed: With the U.S. Civil War raging to the south, McGee warns Canadians that the guns of Fort Sumter had a message for us – the urgent need to form and defend a new “Canadian nationality, not French-Canadian, nor British-Canadian, nor Irish-Canadian – patriotism rejects the prefix.” In a speech as eloquent as it is rich in Canadian themes, McGee speaks of the duty to tamp down religious animosities, and denounces the bigot as Canada’s most dangerous public enemy. McGee’s message is that a liberal spirit will be required to form a Canadian people – and a welcome to new immigrants as brothers: “narrow and most unwise is that species of public spirit, which in the perverted name of patriotism, would refuse him all he asks – ‘a fair field and no favour.’”]

Mr. McGee said: Ladies and Gentlemen, I received some time ago, a warm invitation from my friend, Captain Anderson, the Secretary of this Society, asking me to be present and take part in the proceedings of this evening. It was an invitation given with great cordiality, for an Irish society’s benefit, and the object was to enable the society to assist the friendless emigrant, and the unfortunate resident.

It seems to be incident to our state of society, where we have no legal provision for the poor, no organised system of relief of any public general kind, that there should be a division of charitable labour among our different voluntary societies, – and as I look upon them all, whether under the auspices of Saint Patrick or any other patron saint, as being themselves but members of one vast society – the society of Canada – I did not feel that I could either on Irish or on Canadian grounds, decline the invitation.

It is very true, Mr. President, that you and I will not be found to-morrow worshipping under the same roof, but is that any reason why we should be united here to-night in a common work of charity? With me it is no reason; such differences exist in the first elements of our population: and it is the duty of every man, especially of every man undergoing the education of a statesman, the endeavour to mitigate instead of inflaming, religious animosities. No prejudices lie nearer the surface that those which plead the sanction of religion – any idiot may arouse them, to the wise man’s consternation, and the peaceful man’s deep regret.

If in times past they have been too often and too easily aroused, we must all deeply deplore it; but for the future, – in these new and eventful days, when it is essential that there shall be complete harmony within our ranks, – let us all agree to brand the propagandist of bigotry as the most dangerous of our enemies, because his work is to divide us among ourselves, and thereby render us incapable of common defence.

It is upon this subject of the public spirit to be cultivated among us – of the spirit which can along make Canada safe and secure, rich and renowned – which can along attract population and augment capital – that I desire to say the few words with which I must endeavour to fulfil your expectations. I feel that it is a serious subject for a popular festival – but these are serious times, and they bring upon their wings most serious reflections.

That shot fired at Fort Sumter, on the 12th of April, 1861, had a message for the North as well as for the South, and here in Quebec, if anywhere, by the light which history lends us, we should find those who can rightly read that eventful message. Here, from this rock, for which the immortals have contended, here from this rock, over which Richelieu’s wisdom and Chatham’s genius, and the memory of heroic men, the glory of three great nations has hung its halo, we should look forth upon a continent convulsed, and ask of a ruler, “Watchman, what of the night?”

That shot fired at Fort Sumter was the signal gun of a new epoch for North America, which told the people of Canada, more plainly than human speech can ever express it, to sleep no more, except on their arms, unless in their sleep they desire to be overtaken and subjugated.

For one, Mr. President, I can safely say that if I know myself I have not a particle of prejudice against the United States; on the contrary, I am bound to declare that many things in the constitution and the people I sincerely esteem and admire. What I contend for with myself, and what I would impress upon other is, that the lesson of the last few months furnished by America to the world, should not be thrown away upon the inhabitants of Canada.

I do not believe that it is our destiny to be engulphed into a Republican union, renovated and inflamed with the wine of victory, of which she now drinks so freely – it seems to me we have theatre enough under our feet to act another and a worthier part; we can hardly join the Americans on our own terms and we never ought to join them on theirs. A Canadian nationality, not French-Canadian, nor British-Canadian, nor Irish-Canadian – patriotism rejects the prefix – is, in my opinion, what we should look forward to, – that is what we ought to labour for, that is what we ought to be prepared to defend to the death.

Heirs of one seventh of the continent – inheritors of a long ancestral story, – and no part of it dearer to us than the glorious tale of this last century, – warned not by cold chronicles only, but by living scenes, passing before our eyes, of the dangers of an unmixed democracy, – we are here to vindicate our capacity, by the test of a new political creation.

What we most immediately want, Mr. President, to carry on that work, is men – more men – and still more men! The ladies, I dare say, will not object to that doctrine. We may not want more lawyers and doctors – but we want more men, in town and country. We want the signs of youth and growth in our young and growing country. One of our maxims should be – “early marriages, and death to old bachelors.” I have long entertained a project of a special tax upon that most undesirable class of the population, and our friend the Finance Minister may perhaps have something of the kind among the agreeable surprises of his next budget.

Seriously, Mr. President, what I chiefly wanted to say in coming here is this, that if we would make Canada safe and secure, rich and renowned, we must all liberalise – locally, sectionally, religiously, nationally. There is room enough in this country for one great free people, but there is not room enough, under the same flag, and the same laws, for two or three angry, suspicious, obstructive “nationalities.”

Dear, most justly dear to every land beneath the sun are the children born in her bosom, and nursed upon her breast; but when the man of another country, wherever born, speaking whatever speech, holding whatever creed, seeks out a country to serve and honour and cleave to, in weal or in woe, – when he heaves up the anchor of his heart from its old moorings, and lays at the feet of the mistress of his choice, his New country, all the hopes of his ripe manhood, he establishes by such devotion a claim to consideration, not second even to that of the children of the soil. He is their brother delivered by a new birth from the dark-wombed Atlantic ship that ushers him into existence in the new world, – he stands by his own election among the children of the household, and narrow and most unwise is that species of public spirit, which in the perverted name of patriotism, would refuse him all he asks – “a fair field and no favour.”

I am not about to talk politics, Mr. President, though these are grand politics – I reserve all else for what is usually called “another place”; – and I may add, for another time. But I am so thoroughly convinced and assured that we are gliding along the currents of a new epoch, that if I break silence at all, in the presence of my fellow subjects, I cannot choose but speak of the immense issues which devolve upon us, at this moment, in this country.

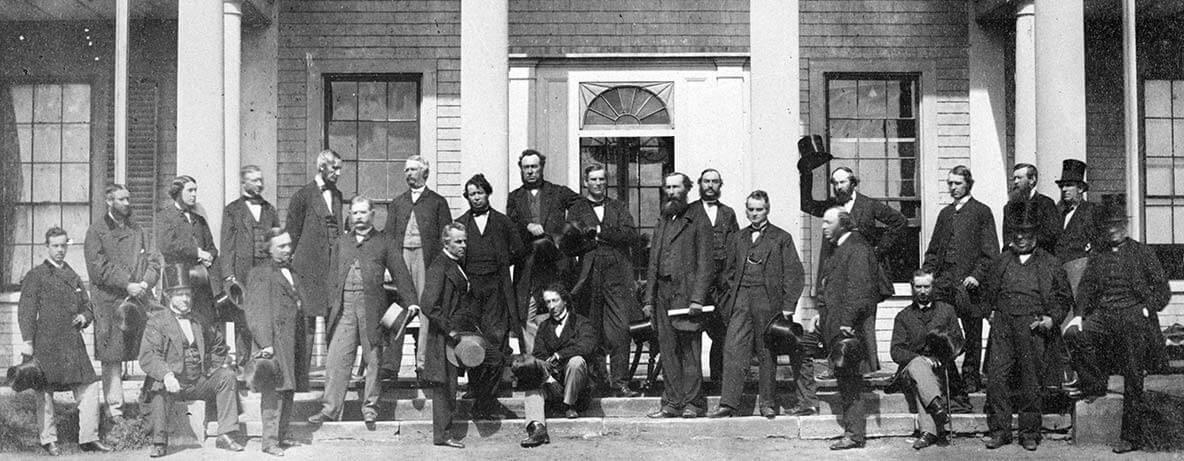

I may be pardoned, perhaps, if I refer to another matter that comes home to you, Mr. President, and to myself. Though we are alike opposed to all invidious national distinctions on this soil, we are not opposed, I hope, to giving full credit to all the elements which at the present day compose our population. In this respect it is a source of gratification to learn that among your invited guests, to-night, there are twelve or thirteen members of the House to which I have the honour to belong – gentlemen from both sides of the House – who drew their native breath in our own dearly beloved ancestral island.

It takes three quarters of the world in these days to hold an Irish family, and it is pleasant to know that some of the elder sons of the family are considered, by their discriminating fellow citizens, worthy to be entrusted with the liberties and fortunes of their adopted countries. We have here men of Irish birth who have led, and who still lead, the Parliament of Canada, and who are determined to lead it in a spirit of genuine liberality.

We, Irishmen, Protestant and Catholic, born and bred in a land of religious controversy, should never forget that we now live and act in a land of the fullest religious and civil liberty. All we have to do, is, each for himself, to keep down dissensions which can only weaken, impoverish, and keep back the country; each for himself do all he can to increase its wealth, its strength, and its reputation; each for himself – you and you, gentlemen, and all of us – to welcome every talent, to hail every invention, to cherish every gem of art, to foster every gleam of authorship, to honour every acquirement and every natural gift, to lift ourselves to the level of our destinies, to rise above all low limitations and narrow circumscriptions, to cultivate that true catholicity of spirit which embraces all creeds, all classes, and all races, in order to make our boundless Province, so rich in known and unknown resources, a great new Northern nation.