This article originally appeared in Modern Diplomacy.

By Stephen Nagy, June 30, 2022

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is an explicit challenge to the post-WW 2 order. This order has brought peace and stability and created the conditions for economic growth in the global north and Global South. It has also brought relative peace and economic integration in the Europe and in the Indo-Pacific.

Today, this order is now being challenged by Russia today but also by China. The consequences could mean that a might-is-right approach and Machiavellian approach to foreign policy will become the new normal for countries like Canada, a self-described middle power.

A Machiavellian order is an order in which larger countries can bully, cajole and pressure, mid and small size countries to do what they are demanded is an explicit challenge to Canadian interests, as well as the interests of like-minded countries such as Japan, Australia, South Korea, European countries and countries in the Global South.

The Trudeau Government has clearly and explicitly criticized the Russian government’s invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Ottawa has coordinated with other middle powers and as we speak through the G-7 Summit in Germany on how to handle Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine.

Unity will be important, especially as energy security becomes more and more critical of an issue for Central and Eastern European countries. The growing food crisis that has manifested as a result of the Russian invasion is also an area that the G-7 will need to coordinate to provide relief to many countries in the Global South.

This message will be further discussed at the NATO summit in Spain. Here, Japan, South Korea, Australia New Zealand will join the NATO members to demonstrate their shared commitment to a rules-based order to pushing back against aggression to change the current order and to find ways to work together to support the Ukraine and resist Russian aggression. Here, Canada has an important role in terms of energy security and food security.

With ample access to energy and food resources, there is a possibility for Canada and other partners such as the U.S. to divert some of its significant grain and energy resources to the Europe to help alleviate some of the stress associated with the invasion of Ukraine.

Coordinated military support as well will be important to ensure that the Ukrainians can resist and eventually take back territory that was taken by force by Russia.

There is an interesting paradox in Canada’s approach. While explicitly criticizing Russia’s might-is-right approach to foreign relations in Eastern Europe and particularly with Ukraine, Canada continues to waver in using the same language in the Indo-Pacific.

The Indo-Pacific region is also facing a might-is-right approach to reshaping the Indo-Pacific order. The use of lawfare, gray-zone operations, military force and belligerent threats all are aimed at reshaping the Indo-Pacific order in such a way that creates a Chinese centric regional order in which China’s neighbors as well as stakeholders that engage in the region will think about China’s interests before their own interests and their interest with Washington.

Canada needs to continue to invest in the Indo-Pacific. A good place to start will be to explicitly state Canada’s concerns about that Machiavellian approach to foreign policy in the region and the efforts by China to reshape the region such that states lose aspects of their autonomy. This will require an Indo-Pacific strategy to be built on a clear objective of how Canada sees the Indo-Pacific Region evolving forward and how Canada would like to contribute to that broader vision of the Indo-Pacific.

Japan, Australia, the United States, Germany, Denmark, and the E.U. have laid out their own Indo-Pacific strategies. They focus on maritime security, a rules-based order, transparency, development and importantly, good governance. We see little rhetoric concerning progressive issues as well as little mention of the core values such as democracy, human rights and freedom of press. This is intentional. These countries and associations understand the heterogeneity within the region.

The-Indo Pacific region is home to soft authoritarian regimes, socialist regimes, democracies and monarchies. Unfortunately, each has very different views about democracy, human rights and progressive issues.

Where they are aligned is in their interests. Their interests are focused on trade, economic integration development, the digital economy, resolving territorial issues through dialogue and consensus-based decision making and not excluding any country region or political entity from the region’s political economy.

Simply, associations and regions like ASEAN, South Asia and the E.U. see inclusivity as a key criterion to the Indo-Pacific peaceful evolution This means any Indo-Pacific strategy that emerges out of these countries does not exclude China or strive to eject non-democratic states.

Rather, their Indo-Pacific strategies focus on inculcating peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region through development, trade, infrastructure and connectivity, institution building, good governance and deterrence.

In the Canadian case, the broader vision for the Indo-Pacific should echo but not necessarily replicate the Indo-Pacific Visions of the country’s mentioned above. Canada’s priority should be peace, stability, open access, a transparent, rules-based order that ensures Canada can have free access to economies and societies throughout the region.

At the same time, Canada’s interests in the Indo-Pacific should include shaping the region such that traditional security issues such as territory issues in the South China Sea, East China Sea, the Taiwan Straits and the Himalayan plateau do not devolve into kinetic conflict that fundamentally disrupts the region’s development and stability.

Traditional security issues are not the only issue that can affect Canada’s interests in the region. Non-traditional security issues such as climate change, terrorism, transnational diseases, extremism are all potential concerns for Canada as it could create instability in the region, disrupt their economies, destabilize supply chains as well as create problems for trading partners.

As Canada celebrates another Canada Day, it should reflect upon what are the key elements of an Indo-Pacific strategy.

Here a six-fold approach may be a useful approach to creating an Indo-Pacific strategy that helps achieve Canada’s national interests in the Indo-Pacific region. A first pillar of an Indo Pacific strategy should be one of Inclusive Development.

Here, Canada can help build stability, improve governance and contribute to broad inclusive development in the region. Through support for NGOs, investment in infrastructure and connectivity, coordinating with regional stakeholders and ensuring that inclusive development results in sustainable and replicable development in the region. Importantly, inclusive development in the region should de-emphasize the progressive character of inclusivity found in the domestic context of Canada as it is less prioritized in the region. This does not mean that a progressive approach is absent but it is sensitive to the local cultures and societies.

A second pillar should focus on Canada’s comparative advantages, Energy and critical mineral security. Based on improvements in environmental technology and technologies that are used to exploit both energy resources and critical minerals, Canada should make this the second pillar of their Indo-Pacific strategy as an open, reliable source of energy and critical minerals.

Canada could carve a position within the Indo-Pacific region in which it is the key provider of energy and critical minerals to industries that use both products. We’ve seen in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine, that energy security has become timely and we expect that energy security and critical minerals to be subject to weaponization in the future in the build-up to or in a conflict.

Consequently, Canada can contribute energy and critical mineral significantly by making this a key pillar in their strategy.

A third pillar should focus on coordinating and investing in Middle Power Diplomacy. In short, Canada needs to coordinate with other middle powers such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand European powers to ensure that the US China Strategic competition does not shape them. Rather, coordination shapes the dynamics of the US China Strategic competition in such a way that it decreases and or attenuates the negative effects on countries we’ve already seen Canada engage in middle power diplomacy with some success.

The 2020 Agreement, in which Canada marshaled middle powers and other countries to join a Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in State-to-State Relations following the arrest of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in China is a good example. We also saw Canada bring together middle powers and the United States to discuss denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula in January 2018.

More coordination of middle powers in the areas of good governance, transparency, energy cooperation and financial cooperation would be a unique but also important contribution by Canada in the Indo-Pacific.

Here, one could easily imagine Canada working with the Partners in the Blue Pacific (PBP) to provide energy security, health infrastructure, good governance to the Pacific Island nations.

We could also see Canada contribute to the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework by marshalling middle powers to support this standard setting agreement that will shape how we think about trade. The standards that we use to negotiate new technologies ,the internet, cyber as well as AI.

A fourth pillar should be supporting Economic security, infrastructure and connectivity. Here Canada needs to find ways to consolidate its own economic security so that is more resilient against economic shocls, outside Canada, as well as inside Canada.

The COVID 19 pandemic is a good example of an external shock to the Canadian economy. We had challenges in terms of acquiring personal protective equipment and other goods as China shut down their country to manage the initial Covid-19 outbreak.

The current COVID-19 policies in Shanghai and Beijing further consolidates the logic that Canada needs to build resilience into its economy, to invest and protect its own economic security.

Internally, the floods in the fall of 2021 in British Colombia also disrupted Canadian exports abroad.

Economic security, resilience and infrastructure and connectivity can help ensure that Canada’s economy remains online and integrated into the global economy and resilient against external and internal shocks. This will require bolstering infrastructure and connectivity at home so that we have world class infrastructure that is resilient against internal shocks.

Also, Canada has a role in contributing to infrastructure and connect to the within the Indo-Pacific region. While we have limited capacities, we have capabilities that can piggyback onto existing infrastructure connectivity programs that are associated with the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. The Japan-India-Australia resilient supply chain initiative and bilateral and other multilateral infrastructure and connectivity initiatives that have come online over the past three or four years. All of this will be important for Canada’s Indo-Pacific strategy in ensuring that Canada’s economic security is based on a resilient economy that is bolstered by infrastructure connectivity at home and abroad.

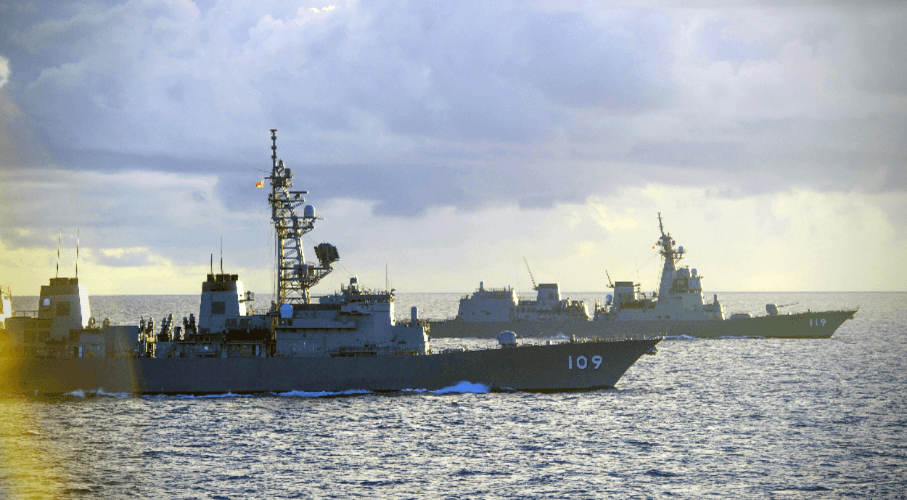

A fifth pillar for Canada will continue to be focused on security and in particular, Maritime Security in the Indo-Pacific region. With sea lines of communication in the Indo-Pacific responsible for about $5.5 trillion in trade every year and energy resources being transported through the key arteries located in the Indian Ocean, Malacca Straits South China Sea, Taiwan Straits as well as East China Sea, Canada has an interest in ensuring that the sea lines of communication remain open, governed by international law and free from coercion.

Cooperation in sea lines of communication will need to take place within existing frameworks or new frameworks. Quad plus arrangements have already taken place in January 2021 Canada participated in the Sea Dragon 21 exercises to provide an opportunity for Canada to monitor and observe Quad exercises.

We also see Canada engage in sanctions monitoring in the East China Sea in an effort to prevent sanctions invasions by North Korea. These activities continue to need to be expanded by working with like-minded countries within the region focused on maritime domain awareness search and rescue, humanitarian relief and disaster assistance and dealing with non-traditional security challenges such as illegal fishing, piracy and others.

While this is not an easy task, this pillar of a Canadian Indo-Pacific strategy is important to contributing to the region’s peace and stability as well it is important for protecting Canadian imports and exports to the region. In 2021, more than $21 billion of Canadian goods went through the region this sum continues to increase as Indo-Pacific nations look to Canada to secure energy as well as agricultural products. Ensuring that sea lines of communication remain open, stable and peaceful will continue to be a critical part of any Canadian Indo-Pacific strategy.

Lastly, a sixth pillar of a Canadian Indo-Pacific Strategy should focus on Climate Change.

The Indo-Pacific region is hosts the three most populated countries, Indonesia, India and China. It is also home to ASEAN. Collectively, the population of the Indo-Pacific region is at least 3.5 billion and the current development patterns suggest that they will have severe water and food security issues as their environment degrades do to climate change and global warming.

More extreme weather systems, the salination of the Mekong and Bangladeshi delta’s as sea levels rise will change the ecology of these critical production areas that that will create social instability, economic stress and likely political instability associated with economic refugees moving to find safer, more predictable geographic locations to leave and work.

We will also see tropical diseases and insects push north and southward disrupting agricultural and social systems.

Canada has a clear interest in investing in climate change mitigation, promoting environmentally friendly governance and business systems and technology transfer that lessen the negative impact of climate change. The scale of the problem will require Canada to pursue this sixth pillar through regional and global coordination.

With a pragmatic and realistic approach that is based on understanding the heterogeneity of the Indo-Pacific region, a Canadian Indo-Pacific Strategy should include but not be exclusive to: Inclusive development, Trade and Economic Residence, Climate Change, Maritime Security, Energy and Critical Mineral Security, and Middle Power Diplomacy.

Stephen Nagy is a senior associate professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.