This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Richard Shimooka, April 17, 2023

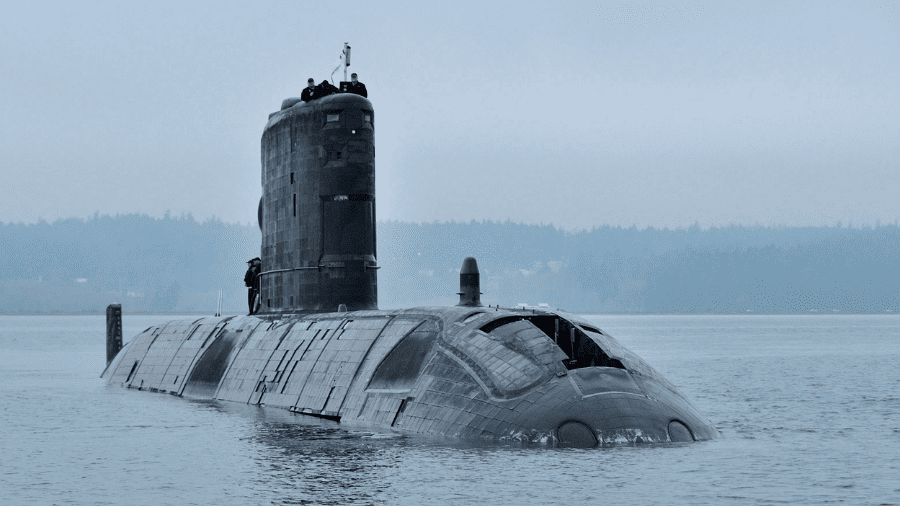

In recent weeks it has come to light that the government is moving ahead with a project to replace its aging Victoria-class submarines, known as the Canadian Patrol Submarine Project (CPSP). While the existing submarine fleet has experienced chequered history since its acquisition in the late 1990s, their replacement must go ahead as planned.

Submarines remain an essential naval capability in the 21st century—particularly for Canada’s great power rivals. China’s sub-building capacity has increased over the past decade, pointing to a major modernization of its undersea warfare capabilities, while Russia’s fleet remains the most potent part of its navy. In reality, the best counter for one submarine is another one, particularly in the difficult conditions of the Arctic. In order to protect its national sovereignty and its maritime interests abroad, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) must develop its sub-surface warfare capability in order to meet the threats it faces.

To start, submarines operate in an operational-maintenance-training cycle, like many other military capabilities. However, more so than any other platform, a submarine fleet requires maintenance to keep the vessels operational and safe. Thus, whereas many capabilities operate roughly on a rule of three, submarines tend to work on a rule of four—for one submarine to be continuously at sea at any one time, three additional hulls are required in various states of regeneration, training, and deep maintenance. A rough example can be seen with the Royal Navy’s continuous at-sea deterrence—which requires four submarines in a class in order to sustain one operational vessel at sea.

While the RCN possesses four Victoria-class submarines, it has been unable to sustain a single vessel at sea consistently through the class’s history and is unlikely to in the future. Perhaps the most serious event was the grounding of HMCS Corner Brook in 2011, followed by a series of incidents that has effectively kept the vessel out of service since. This has had consequences across the entire submarine fleet, severely hampering the RCN’s ability to generate boats for operational deployment.

Even when the Corner Brook re-enters service, the RCN faces other challenges. Maintenance cycles will take considerably longer and require more work as the fleet ages in future years to ensure that the submarines are safe to operate in an undersea environment. Furthermore, the armed forces face a severe personnel shortage, and the submarine force is no exception. While Canadian submarine crews are highly trained and are well regarded among our allies, they too have been hit hard by the recruiting and retention crisis. Submariners already operate in particularly challenging conditions that affect many of their willingness to remain in the service, but the current state of the submarine fleet is a serious contributing factor. The lack of time at sea, as well as manning a thirty-year-old vessel, has seriously impacted the RCN’s ability to generate crews for these vessels and maintain their high level of proficiency.

In light of these challenges and the remaining lifecycle of the Victoria class, approximately 15-20 years, Canada must start the CPSP now in order to ensure an orderly transition to a new fleet. The RCN is looking at a major expansion of its submarine force—to either eight or, ideally, twelve vessels—this would essentially ensure that Canada would have at least two, if not three, submarines operating at sea at any one time. This would also enable having one available for two or even three coasts simultaneously, which would significantly enhance Canada’s security. Such a fleet will come at a significant cost—potentially $60B dollars according to some early discussions.

First off, acquiring submarines would not look like the Canadian Surface Combatant project or any other ship built as part of the National Shipbuilding Strategy. The boats will be of an existing design that will be constructed in a foreign yard, with some relatively limited modifications undertaken, either in that country or upon delivery in Canada. Greater modification entails increased costs and production time—which are aspects the RCN seems eager to avoid and has signalled its willingness to accept a less customized platform. If this is the case, the costs should be relatively close to the contractually agreed-upon cost, with limited potential for escalation.

Instead, the main cost driver is likely to be Canada’s requirement for offsets for any amount spent abroad to be reinvested by the foreign firm back in Canada—known as the Industrial Technical Benefits policy, and the Value Proposition (ITB/VP). Offsets are widely regarded in the academic literature and many developed states as economically inefficient as they drive up contract costs— which can reach as high as 30 percent depending on the situation—and are inefficient at delivering industrial outcomes. Yet Canada remains wedded to this approach, despite its obvious failings. More fulsome discussions of the ITBs will likely be the topic of a later column.

Some attention should be paid to the potential requirements the RCN will demand, which will dramatically narrow the potential market options. Two are likely to be paramount. The first will be long-range, in large part driven by a desire to undertake Arctic patrols with the vessel. Transiting to the north from Halifax or Esquimalt and having a meaningful time on station will all but rule out all but the largest classes of diesel-electric submarines available on the international market. This requirement will also aid in Canada’s ability to increase its presence in other key strategic areas, like the Indo-Pacific.

The second major requirement will likely revolve around interoperability, particularly with the United States. A poorly understood aspect of the Victoria class was the near-total upgrade of its combat systems soon after their purchase, particularly its weapons, fire control, and sensors. These RCN systems were replaced directly with American ones or close amalgams to them. This had a number of practical benefits: the United States possess the world’s largest logistics supply chain, is Canada’s closest ally, and is widely regarded for its undersea warfare prowess. Thus ensuring interoperability enhances any vessel’s potential combat capability.

Given the above-discussed preference for acquiring a class of large submarines with minimal modifications and the requirement for interoperability, Canada’s options narrow significantly. There are likely only two options that generally fit these requirements—the Japanese Teigei, and the South Korean Dosan-Ahn Chango classes. These are large and highly advanced submarines that likely have significant interoperability with U.S. systems. Acquiring submarines from one of these two countries would also be a tangible example of Canada’s commitment to the region after the promulgation of the Asia-Pacific Strategy.

While several European states produce submarines, they all have significant shortcomings from Canada’s perspective. For example, Germany and Sweden build classes of submarines that are smaller and more ideal for coastal defence, as they have small coastlines with shallow waters. The outlier is Spain, which is currently producing a new submarine, known as the Isaac Peral class, which is near the requisite size required by the RCN. However, it has faced significant development challenges which may impact its potential.

Moreover, one cannot discount that some of these manufacturers will attempt to lobby the government to adopt less stringent requirements that would allow them to compete—even if it comes to the detriment of the Navy. This has occurred in a number of instances over the past few decades, resulting in less-than-optimal platforms being selected by the government.

While the RCN has faced significant challenges in maintaining the Victoria class fleet over the past few decades, this should not dissuade Canada from pushing forward with its replacement. Submarines remain a key area of warfare, and Canada must make investments in this area if it wants to adequately provide for the country’s security.

Richard Shimooka is a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute. He previously held fellowship positions at the Conference Defence Associations Institute, and Queen’s University’s Center for International Relations and the Defence Management Studies Program.