By Sergey Sukhankin

May 7, 2025

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has forever changed global commodities markets. The economic sanctions subsequently imposed on Russia exposed multiple risks related to (over)reliance on a single or dominant suppliers of critical materials (Sukhankin 2024a).

The European Union (EU) was hit particularly hard thanks to its decades-long reliance on Russia’s inexpensive commodities. The EU’s dependence also made it vulnerable to external pressure and blackmail.

The “Russia sanctions” fallout has revealed a much bigger problem. While natural resources will continue to be used as a geopolitical weapon in the unfolding East-West rivalry, the focus is likely to shift from hydrocarbons to critical minerals in the medium-term. This trend is visible in China’s series of decisions (2023–25) to restrict exports of several types of critical metals and technologies (Shivaprasad, Lv, and Jackson 2024) that are instrumental for innovation and technological sectors of Western economies.

Among those critical minerals, uranium will likely become a main “metal of discord” between global powers, thanks to the strategic importance of nuclear energy and the relative rarity of the mineral. Further complicating matters, uranium’s leading global producer, Kazakhstan is reportedly considering nationalization of its uranium sector (Kazakhstan’s economy is heavily dependent on China, while its security is influenced by Russia) (Energy Intelligence 2025). Nationalization could have a major impact not only on the global uranium industry but also restrict Western access to Kazakhstan’s uranium sector, which would in turn become further dependent on Russia and China.

The global uranium industry – currently dominated by a small group of countries – is entering a period of “bifurcation,” or divergence, which poses both threats and, especially for Canada, opportunities. This commentary will discuss the strategic meaning of bifurcation; how real the process is; its related challenges; and, most importantly, how resource-rich Canada can capitalize on the looming seismic changes in the uranium industry.

The global uranium industry and the issue of bifurcation

The state of the (unenriched) uranium industry post-2022

The fact that nuclear power will become one of the key sources of clean energy in the 21st century was reconfirmed during the COP28 summit (December 2023) in the UAE where 25 countries signed on to a “Declaration to Triple Nuclear Power” by 2050 (a number that has since grown to 31) ( US Department of Energy 2023). This implies that the amount and share of nuclear power in the global energy mix is set to increase dramatically in the forthcoming years. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) in addition to the already existing 420 nuclear reactors worldwide, another 63 reactors are currently under construction, and the lifespan of another 60 reactors is being extended (Home 2025).

Clearly, this is going to result in a spike in demand for uranium. Availability of supply should equally concern both developed and developing economies seeking to expand their nuclear capacity. The number of producers of uranium and countries with enriching capabilities is limited, and their behaviour is frequently affected by geopolitical factors. This can cause a shortage of supply and destabilization of the market. In fact, under the shadow of geopolitical developments many experts are already warning about a looming deficit of uranium to cover both actual and future needs (Yeoman 2025).

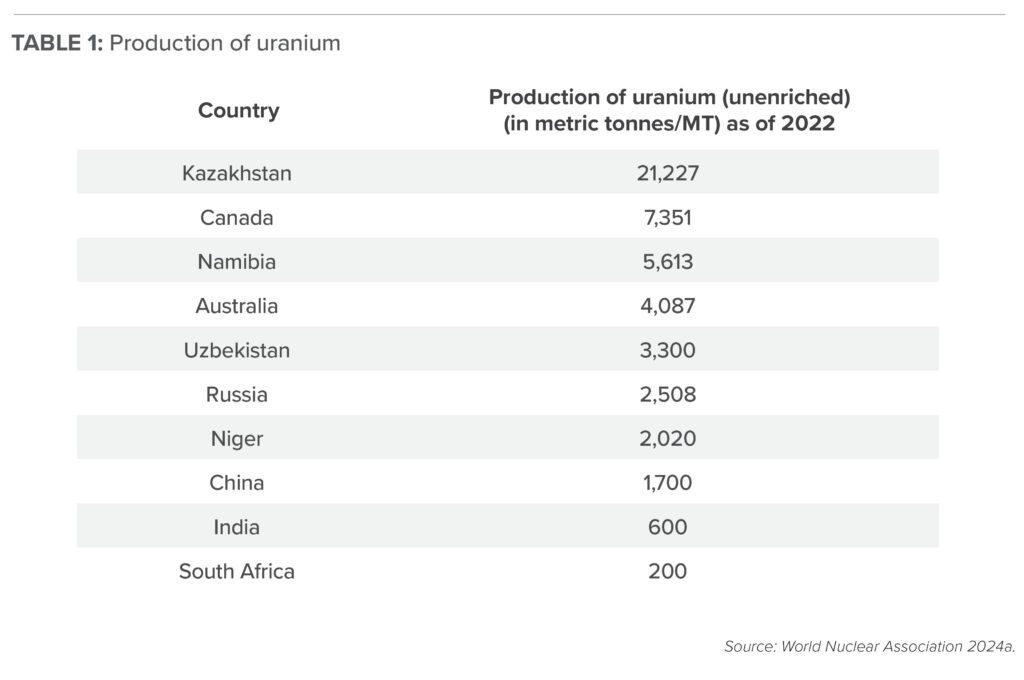

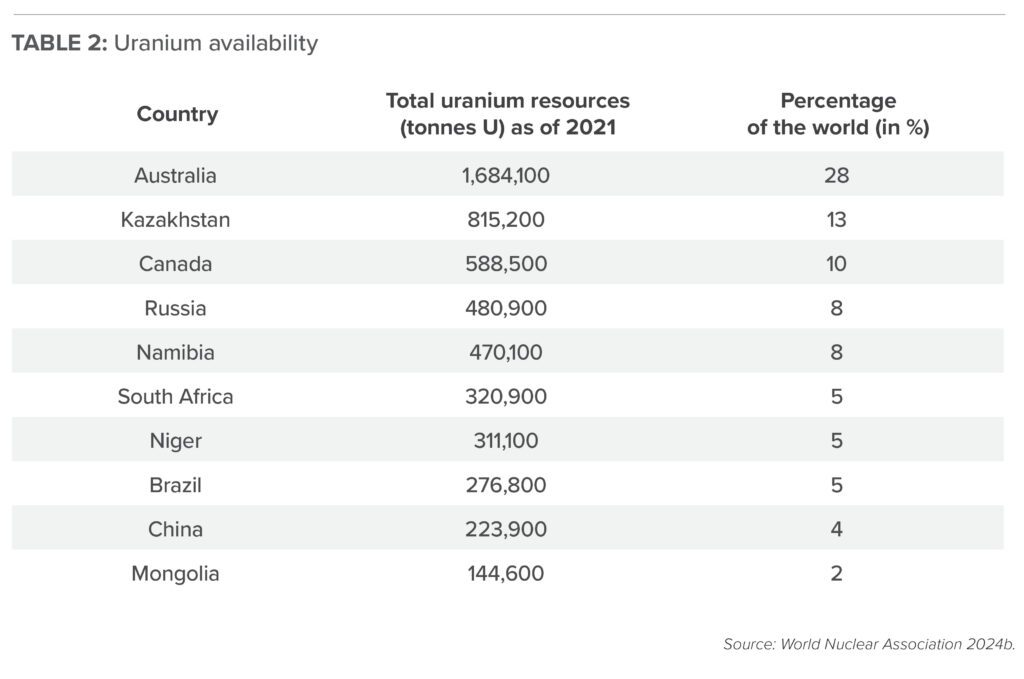

In terms of total uranium resources and production, the following countries form the core of the global uranium industry.

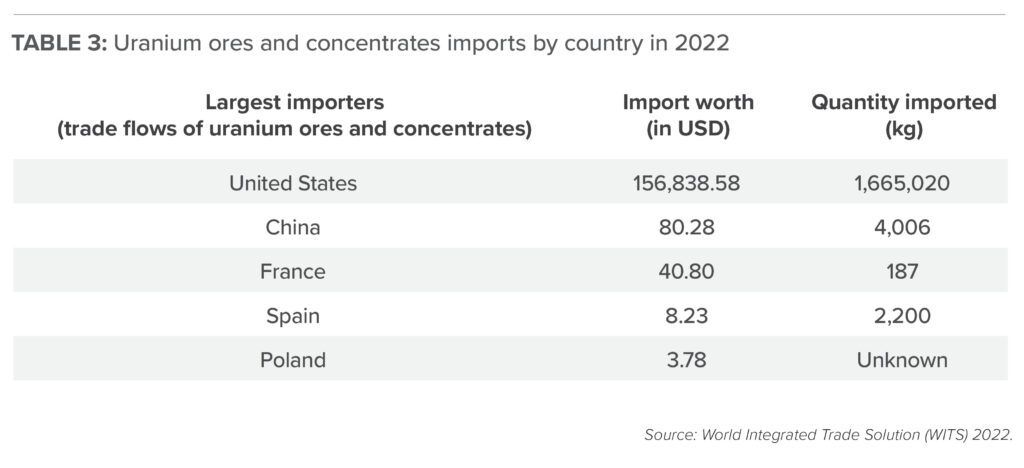

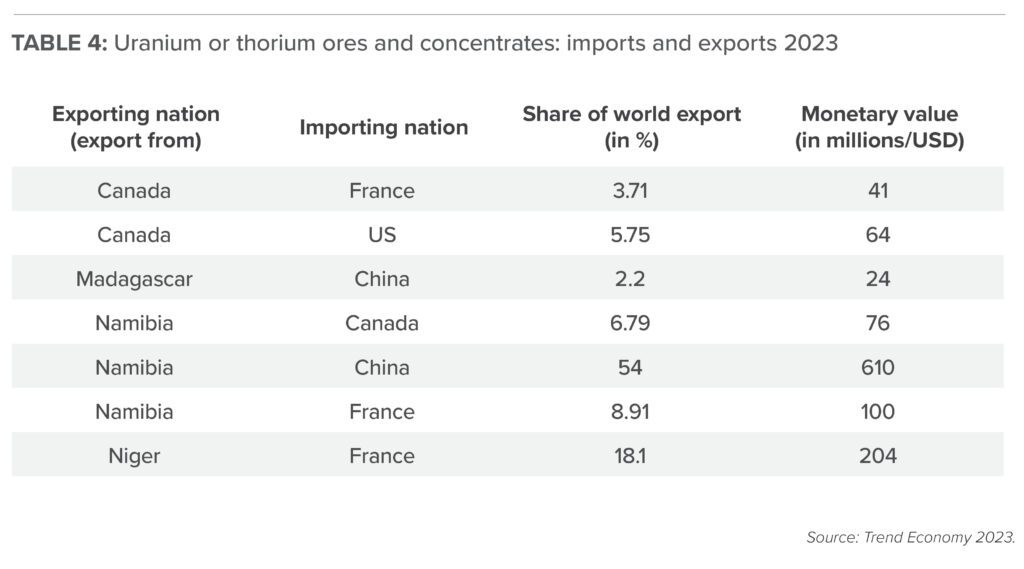

Crucially, according to statistics provided by the major exporters, the largest flows of exports of “uranium or thorium ores and concentrates” in 2023 presented the following picture:

This said, the most notable growth in export-import dynamic in 2023 was demonstrated by China and Namibia that, based on some sources, increased by 54 per cent. It’s important to note, relating to the dynamic of uranium flaws, that in 2023 US nuclear generators used 32 million pounds of imported uranium concentrate, while only 0.05 million pounds were domestically produced (the US is one of the world’s key consumers of uranium). This means that imports accounted for 99 per cent of the uranium they used in 2023 to make nuclear fuel (US Energy Information Administration 2025), which underscores its strategic dependence on external suppliers of unenriched uranium vital for its ambitious plans for generation of nuclear energy.

Bifurcation in the uranium market

Emerging supply shortages should not be seen as an example of a simple supply crunch caused by purely market processes. This challenge has a structural nature caused by the unfolding bifurcation in the global uranium industry, which is fuelled by geopolitical rivalries between Western and non-Western countries. As a result, the global uranium industry is becoming increasingly split into two parts: Western countries are becoming more interested in sourcing their uranium supplies from politically stable, culturally and politically proximate actors (such as Canada and Australia), whereas influential non-Western actors (such as China) whose consumption of uranium is also growing prioritize securing supplies from such actors as Kazakhstan, Niger, and similar sources.

From an economic point of view, the term bifurcation refers to the situation when prices for a certain item are divided into two distinct streams deriving from, for example, an environmental premium on minerals produced under more sustainable regulations; or a regional premium, with increased taxes and prices on minerals not produced in domestic or preferred markets (The Oregon Group 2024).

Aside from purely economic aspects, the process of bifurcation has an apparent geopolitical pivot. On the one hand, the stability of the uranium industry is premised on a combination of several politically driven factors such as stability, accessibility of appropriate infrastructure, and the safety of shipping and transportation. While the process of bifurcation in the global uranium industry is undeniable, many experts rightfully point to the danger of this process and related challenges. Among the most frequently mentioned are repercussions for international trade and investments, risks of disruptions in critical mineral supply chains, and a hindrance to transition toward lower carbon energy systems (Shi and Shen 2023). Indeed, from an economic point of view the process of bifurcation in the global uranium industry is an undeniably negative phenomenon that affects both developed and developing economies. While the role of the West in the process of unfolding bifurcation is marginal, the main task now is to find the most effective ways to minimize the harms. For this, it is critical to understand the roots of the problem and surrounding challenges.

Bifurcation of uranium production and “red flags” for the West

As stated earlier, bifurcation in the global uranium industry should not be viewed as phenomenon driven by purely economic factors. It reflects the ongoing East-West geopolitical struggle, which poses multiple risks to the Western countries and their economies. Three cases exemplify this.

The case of sub-Saharan Africa

Many African countries are rich in natural resources including uranium: Namibia (5,613 metric tonnes), Niger (2,020 metric tonnes) and South Africa (200 metric tonnes) are Africa’s main producers of uranium. Notably, supplies of African uranium cover above 25 per cent of the EU’s imports, with France – where over 60 per cent of electricity is generated by nuclear reactors (EUROSTAT 2025) – being the top importer. Yet, considering the most recent geopolitical developments in Africa, the EU (and France in particular) are at risk of losing access to African deposits.

In 2023, a military coup in Niger brought in new authorities that started introducing anti-Western/French measures aimed at squeezing Western investors from the country’s uranium industry. The end of 2024 brought particularly bad news for Orano, a French nuclear fuels company operating in Africa. First, the company stated that it had been forced to suspend production at the Somair mine in the north of Niger following last year’s closure of the main export corridor (Kar-Gupta, Patton, and Felix 2024). Later, authorities of Niger took control of the Somair uranium mine, where Orano’s share is about 63 per cent (Patton, Mallet, and Njini 2024).

French companies were not the only targets. Canadian miner GoviEx Uranium was affected as well: the company stated that it was stripped of its right to develop one of its uranium projects in Niger. While the company said it “reserves the right to challenge the decision to withdraw the mining rights before the competent national or international jurisdictions” (Njini 2024) it is highly unlikely that this will bear any fruit. The fundamental problem lies in the fact that Niger – akin to many other countries of sub-Saharan Africa – may have changed sides and is now increasingly looking to partner with authoritarian regimes rather than the West.

In addition to China – whose economic, cultural, and even paramilitary presence in Africa has grown exponentially within just a decade (Sukhankin 2023a; Sukhankin 2023b) – the “Russian factor” looms large, posing great danger to Western economic activities in the region in general and the uranium industry in particular.

In addition to Niger, whose new authorities have openly taken a pro-Russian stance (Kar-Gupta, Patton, and Felix 2024) by hosting Russian mercenary formation the Wager Group/African Corps, two other uranium-endowed countries, Namibia and Tanzania, are strengthening ties with Russia. Specifically, in 2023 Rosatom announced that in 2029, the company plans to start commercializing uranium in Namibia, which reportedly holds 7 per cent of the world’s uranium reserves (RIA Novosti 2023). Similarly, in Tanzania, Rosatom is working on the Mkuju River project at the Nyota deposit, which contains 152 million tons of triuranium octoxide, a uranium compound, and a yearly production capacity of 3,000 tonnes (Atomic Energy 2023). These developments clearly point to the fact that for European and Western companies, sourcing uranium in Africa will become increasingly problematic and risky. Thus, from a strategic and long-term point of view it may not be wise to commit to risky investments in Africa given geopolitical shifts and turbulences.

The case of Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is the global leader in production and second largest in terms of uranium resources. The country’s role in the global uranium sector is critical and, given the post-2022 geopolitical changes, is bound to grow further. The role of Kazakhstan in the global supply chain of uranium is a mixed blessing, which was clearly demonstrated by the recent case with Cameco Corporation, the world’s largest publicly traded uranium company, based in Saskatoon (Canada).

In 1996, following Kazakhstan’s independence in 1991, Cameco and the National Atomic Company Kazatomprom JSC (Kazatomprom) set up a Joint Venture: Inkai LLP (JV Inkai)(Kazatomprom holds a 60 per cent interest with Cameco holding the remaining 40 per cent) – with agreement on extraction of uranium, which was prolonged in 2016 until 2045 (AKSII 2025).

However, at the beginning of 2025, Kazakh authorities declared a stoppage of production of uranium by JV Inkai due to a “failure to supply proper documentation” (EurAsia Daily 2025) – jeopardizing a fruitful co-operation between Canadians and Kazakhs. Even though mining operations later resumed, the event produced a shockwave effect on Cameco’s top management and led to an abrupt temporary fall in the value of the company’s stock (Mining.com 2025). More bad news came later, when technical issues (the lack of sulphuric acid) and challenges with transportation made it likely that the amount of mined uranium would fall short of its target production by at least 20 per cent (Mamyshev 2025).

These troubling developments should be seen as a small part of much bigger and more daunting challenge. The story with JV Inkai suggests that Canadian (and potentially Western) investments in Kazakhstan’s natural resources and uranium in particular might fall prey to the East-West geopolitical rivalry. Despite Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s strategic pledge to make the most of the country’s impressive potential in critical minerals, the country`s ability to deliver on its ambitious plans seems questionable (Sukhankin 2024b).

This primarily derives from the fact that the country’s autonomy in strategic decision-making is constrained by dependency on Russia and China. As for the former, Kazakhstan’s ability to transport uranium to end users is inseparable from Russian control of its main logistical and transportational hubs. It is true that, as claimed by Kazakh authorities, today approximately 64 per cent of its uranium is transported via the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, a.k.a. the Middle Corridor), which incorporates rail, road, and maritime transport, linking major economic centres across China, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Europe. The route begins in China, where goods are loaded onto rail freight services originating in industrial hubs like Xi’an, Chongqing, and Urumqi. These shipments are transported westward through Kazakhstan, utilizing an extensive railway network that connects key transit hubs such as Dostyk, Altynkol, and Khorgos.

Upon reaching the Kazakh Caspian Sea ports of Aktau and Kuryk, cargo is transferred onto maritime vessels that cross the Caspian Sea, a crucial yet challenging segment of the corridor. The ports of Aktau and Kuryk play a significant role in facilitating trade between Central Asia and the South Caucasus (Aguiar 2025) – which does not go through Russia’s territory (Interfax 2024). However, should relations between Russia and Kazakhstan (or Russia and the EU) deteriorate, Moscow is more than capable of creating problems in transportation along the Middle Corridor, given its role and presence in South Caucasus as well as growing ties with Iran (Sukhankin 2025a). Furthermore, while no explicit data on the matter is available, Russia’s Rosatom (directly and via subsidiaries) is understood to hold stakes ranging between 30 to 70 per cent in companies operating six different mines in Kazakhstan. Its share in uranium enrichment in Kazakhstan – Russia-provided technologies are said to be far less expensive than analogues presented by French and American competitors – is also prominent (Siddi and Silvan 2023). On top of that, a potential deal on Kazakhstan’s first Nuclear Power Plant (NPP), where Russia is expected to play a role (Sukhankin 2024c) could further strengthen Russia’s position in Kazakhstan`s nuclear industry.

Thus, despite its undeniable richness in natural resources, geopolitical factors make Kazakhstan – as well as other countries of Central Asia and the Caspian Sea region – a risky option for the EU and Western countries in pursuit of diversification of supplies of energy and critical minerals (Sukhankin 2025b). Interestingly, similar suggestions have appeared in Kazakh media and information outlets. For instance, local economist Rakhimbek Abdrakhmanov noted that many experts in Kazakhstan connect the whole situation with JV Inkai with behind-the-scenes activities of the Rosatom corporation, which controls (directly and via subsidiaries and joint ventures with local companies) up to 58 per cent of Kazakhstan’s uranium reserves. He also noted that the mining stoppage might have been related to Cameco’s decision (after February 2022) to change its transportation routes to avoid trespassing Russian territory (Karatayeva 2025).

In case Kazakhstan chooses to pursue an approach that confronts or challenges Russia in any significant way, Moscow could take an even tougher approach, ranging from economic measures and obstacles to trade, to sabotage and provocations. At this juncture, the story of the Kazakh-EU would-be lucrative oil partnership is quite telling. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Tokayev discussed with EU officials how oil-rich Kazakhstan could assist the EU in reducing its dependence on Russia’s oil. Immediately after this conversation the deadly explosion at Kazakhstan’s Tengiz oil field occurred. Some experts argue that Russia played a role in the blast – in effect, “sending a message” to Kazakh authorities (Sukhankin 2024c).

One should never underestimate Russia’s resolve to act as a spoiler in pursuit of its geopolitical objectives. That said, even if no such incidents occur and Canadian uranium mining companies manage to shift to alternatives to Russian-based transportation routes, such as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, challenges will not disappear.

On the one hand, the Canadian side has already voiced concerns about technical and transportation issues related to the above-mentioned Middle Corridor (EurAsia Daily 2024). On the other hand, transportation via the Middle Corridor does not eliminate the geopolitical constraint. Problematic Turkey (and its proxy Azerbaijan), as well as currently openly pro-Russian Georgia, are the other key nexuses of the Middle Corridor, making this route an unreliable alternative for the West.

In the geopolitical games related to Kazakh-produced uranium, Russia is only part of a bigger problem. China’s role should be seen as a sort of éminence grise of the global critical metals industry, including uranium. Over half of Kazakhstan’s uranium production is now destined for China (Mann 2025), which signifies both Kazakhstan’s and Central Asia’s strategic orientation on Indo-Pacific markets and China in particular. Furthermore, Russia may be on its way to ceding (at least in part) control over part of Kazakhstan’s uranium market to China, which could also signify Russia’s weakening positions in Central Asia. This is exemplified by the recent deal – though financial aspects have not disclosed by either party – between Uranium One Group (a subsidiary of Rosatom) and the SNURDC Astana Mining Company Limited (a subsidiary of Chinese State Nuclear Uranium Resources Development Co., Ltd) with the former selling 30 per cent of its shares in northern Kazakhstan-based uranium mines (Atomic Energy 2025). While it is not clear why the deal was concluded, some experts have claimed that the move could be viewed as Rosatom’s intent to avoid international sanctions: uranium – which is now formally owned by a Chinese company – would still be enriched by Russia and later transported to the US as “Chinese” (Serikov 2025a).

Other experts, however, claimed that this move primarily signifies China’s growing presence in Kazakhstan, where the country is rapidly expanding its footprint in the local sector of natural resources (Volobuyev and Lakstygal 2024). In any event, China’s growing involvement in Kazakhstan’s uranium sector – coupled with Russia’s continued presence in the country – is another example of the ongoing bifurcation in the global uranium industry. As noted by Kazakh experts, in the future, locally mined uranium is likely to be mainly destined for Russia and above all China, whereas Canada is likely to become a “Western powerhouse,” formalizing the global division of the uranium production (Serikov 2025b).

The role of Canada

In case of undersupply of uranium, the outlook for both the US, and arguably the EU – whose relations with Russia are unlikely to improve – looks bleak. In addition to the fact that Russia and China together control over 50 per cent of the world’s uranium enrichment capacity (Baskaran 2025) – most Western countries do not have enough domestic resource to satisfy their needs. One viable alternative to sub-Saharan Africa and Kazakhstan (in case new obstacles for doing business will emerge) could be Australia, which is one of the world’s leaders in terms of uranium reserves. However, due to generally unfavourable public opinion (Pavlich and Kennedy 2024) and policy constraints (Hunt 2024) Australia`s capacity for production of uranium remains limited. Furthermore, due to production problems at the Olympic Dam and Ranger mines in 2022 – 2023, Australia’s uranium exports to the EU dropped by 82 per cent.

Therefore, realistically speaking, the most workable option for the West to source uranium is Canada, which has two key qualities – abundance of uranium and (geo)political predictability – that are in short supply in both sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia.

Canada has a long and successful history in production of uranium that goes back to the 1930s. In effect, for a long time Canada remained the world’s number one producer of uranium, ceding leadership to Kazakhstan first in 2009 and again in 2018 (LS 2018). However, geopolitical destabilizations and the skyrocketing price of uranium have led to speculation that Canada could once again regain its global leadership in production of this vital resource through an increase in domestic production, which would not only create jobs and revenues but also minimize geopolitically driven risk factors.

The boost to the domestic uranium industry could eventually come from new projects in places such as Nova Scotia, where an intense debate on lifting the mining ban on uranium is currently taking place (Halef 2025), and Nunavut.

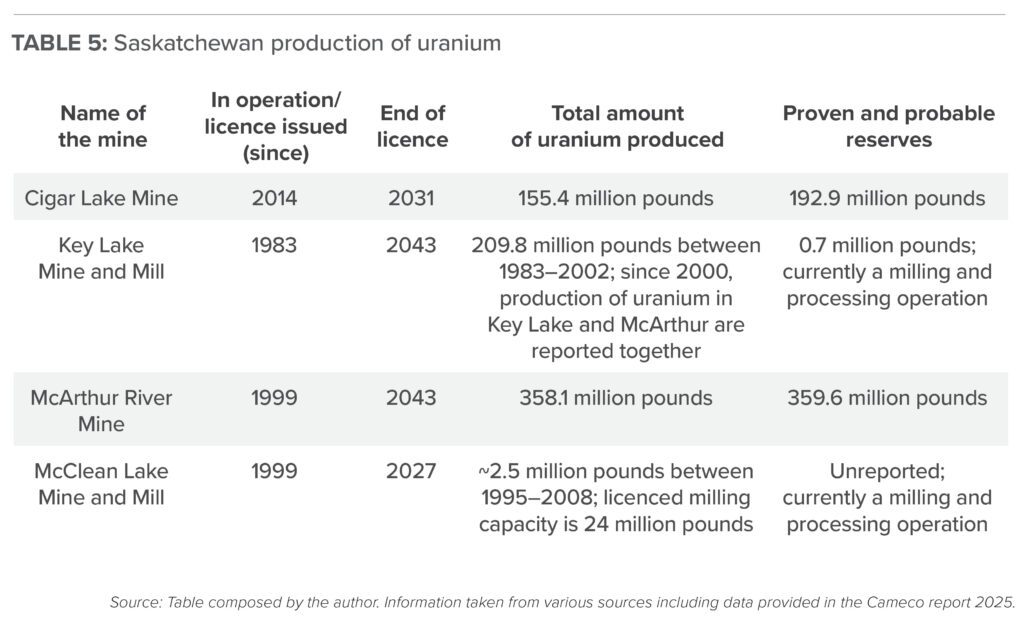

But for now, Saskatchewan’s role will be paramount in Canada’s ability to regain global leadership in production of uranium. All of Canada’s current production comes from the Athabasca Basin, and, as of 2022, the province was ranked as the world’s second-largest producer of uranium, towering above such countries as Namibia and Australia (Saskatchewan Government 2023).

In the future, three additional uranium mines – Wheeler River Project, Rook I, and Patterson Lake – are likely to become operational in Saskatchewan, which, in the case of approval, will boost the province’s uranium output. It is also worth noting that Saskatchewan’s competitive advantage in producing uranium should not be exclusively reduced to the sheer amount of resources available. Its uranium production and related operations follow the highest environmental norms and standards, which is overseen by the Northern Saskatchewan Environmental Quality Committee (NSEQC), established by the province in 1995. Thus, while it is hard to accurately estimate the total depth of resources wealth – different sources provide different numbers with Cameco estimating reserves in Saskatchewan to be approximately 547 million pounds, whereas the Saskatchewan government refers to 1.5 billion pounds of recoverable uranium (Saskatchewan Government 2025) – the province boasts vast uranium deposits while offering a high degree of sustainability.

In 2023, the Russo-Ukrainian war reached its first one-year mark. Amid continued destabilization of the global uranium sector, Saskatchewan boosted its exports of uranium to the EU, which already was one of two (along the US) primary importers of Saskatchewan-produced uranium (World Integrated Trade Solution 2025). In that year, exports of uranium to the EU increased by 306 per cent, reaching an impressive $1 billion in monetary terms. As provincial Trade and Export Development Minister Jeremy Harrison said, “Saskatchewan exports are making their way to new markets at record levels, creating jobs here at home and providing global food and energy security for the world. Saskatchewan’s newest trade and investment office, located in Berlin, is strengthening our bilateral relationships with jurisdictions across Europe and is expanding the reach of our exports” (Saskatchewan Government 2024).

Similarly, the role of Saskatchewan in Canada’s ability to regain the title of the world’s main producer of uranium and thus emerge as a global force balancing negative trends caused by geopolitical instability was highlighted by two other prominent experts. From his side, provincial Energy and Resources Minister Jim Reiter stated that “Saskatchewan’s uranium is key as the world looks to transition to sustainable power generation and source minerals from secure, democratic regions” Cameco President and CEO Tim Gitzel added that “Canada’s global reputation as a stable, reliable supplier of uranium is truly a Saskatchewan success story, given that all Canadian uranium is produced in this province. Cameco’s vision of energizing a clean-air world acknowledges the increasingly important role we know nuclear power must play in meeting the growing global demand for decarbonization, electrification, energy security and affordability” (Saskatchewan Government 2023).

In broader terms, strengthening import-export ties in the domain of uranium between Saskatchewan (Canada) and EU countries should not be seen as the only goal. In effect, uranium could become a strategic plank in boosting Saskatchewan’s international trade and access to foreign markets. For example, crucially for Saskatchewan – and equally so for Canada, given the state of US-Canadian relations – the province’s international office in Berlin can help facilitate trade between the province and the world’s third-largest economy, which is looking for strategic natural resources to fuel its economic growth.

Conclusion

Projections from the World Nuclear Association explicitly show that global uranium supply deficits will explode in the 2030s as new reactors come online and the consumption of uranium across the world spikes (Oil price 2024).

In the meantime, despite US President Donald Trump’s flamboyant promises to stop major conflicts worldwide, there is every reason to believe that the global geopolitical situation will remain tense and existing uncertainties are unlikely to disappear. Amidst raging geopolitical turbulence and growing East-West geopolitical confrontation that is bound to hinder the global uranium industry, Canada – with its current 15 per cent of the world’s share of uranium production and clear potential for growth (World Nuclear Association 2024a) – should become a stabilizing factor capable of balancing negative externalities.

Crucially, essential steps in this direction are already being made – exemplified by growing economic and trade ties between Saskatchewan and Europe. At the same time, it is also quite clear that the US will not be able to accomplish its ambitious nuclear power generation goals without Canadian uranium – unless, of course, anti-Russian sanctions are lifted completely. Yet, as the history of post-1991 dependence on Russia has demonstrated, Russian political leadership is willing to sacrifice its beneficial trade ties for other geopolitical goals or ambitions.

The 1993 “uranium deal” between the US and Russia highlights the risks of collaborating with Russia. The deal, which involved the disposition of highly enriched uranium (HEU) extracted from Russian nuclear weapons, gave Russia exclusive rights to enrich uranium for the US. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, bilateral relations between Russia and the US broke down, causing the US nuclear industry serious problems. Some experts have correctly called Russian President Vladimir Putin’s current uranium export restrictions “a gift for Canada” (Resource Works 2024). However, the provinces may nonetheless face obstacles that prevent them from fully capitalizing on Russian sanctions as well as geopolitical destabilization in Africa and the sudden challenges arising in Kazakhstan.

A key challenge is Canada’s onerous regulatory delays and slow development of new mines, the Nexgen Rook 1 being the obvious example. Another concern, especially for uranium producers, could be shrinking profit margins if more Canadian uranium pours into the global market. This could worsen further if anti-Russian sanctions are lifted and Kazakhstan remains a stable supplier.

However, the geopolitical rivalry and struggle for markets between East- and West-led blocks is unlikely to abate, even if the Ukraine War ends. Indeed, China’s rapid economic growth and mounting ambitions will likely further intensify the struggle for strategic natural resources.

Given the West’s weakening positions in the resource-rich Global South, it would be unwise for resource-stripped Western economies and their regional partners to prolong their (over)reliance on politically unstable suppliers of critical natural resources.

The bottom line is that rogue countries will always seek to exploit the vulnerabilities of their strategic rivals. The West needs to work together to strategically counter these threats and pre-empt future crises. For the nuclear industry, some of the changes – such as changing existing supply routes, logistics, and areas uranium sourcing – will be painful, but necessary.

Bifurcation of the uranium industry is happening whether we like it or not. The question for the West is, do you want to be on trustworthy, politically stable Canada’s side of the supply chain, or risk rolling the dice on Russia?

About the author

Dr. Sergey Sukhankin is a senior fellow at the Jamestown Foundation (Washington, DC) and a fellow at the North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (NAADSN).

References

Aguiar, Paulo. 2025. “The Middle Corridor: A Route Born of the New Eurasian Geopolitics.” Geopolitical Monitor, January 23, 2025. Available at https://geopoliticalmonitor.com/the-middle-corridor-a-route-born-of-the-new-eurasian-geopolitics/#:~:text=The%20Middle%20Corridor%2C%20also%20known%20as%20the%20Trans-Caspian,both%20Russia%E2%80%99s%20Northern%20Corridor%20and%20the%20Suez%20Canal .

Association “Kazakhstan Council of Foreign Investors” (AKSII). 2025. “Cameco.” AKSII, assessed April 2, 2025. Available at https://fic.kz/ru/kfica/members/25 .

Atomic Energy. 2023. “Росатом намерен добывать уран в Намибии и Танзании.” [Rosatom intends to mine uranium in Namibia and Tanzania .] Atomic Energy, July 20, 2023. Available at https://www.atomic-energy.ru/news/2023/07/20/137397.

Atomic Energy. 2025. “’Uranium One’ Росатома продала китайской SNURDC 30%-е доли в казахстанских урановых компаниях ‘Хорасан-U’ и ‘Кызылкум.’” [Rosatom’s Uranium One sold 30% stakes in Kazakhstan’s Khorasan-U and Kyzylkum uranium companies to China’s SNURDC] Atomic Energy, January 30, 2025. Available at https://www.atomic-energy.ru/news/2025/01/30/153064.

Cameco Corporation. 2025. “Management’s discussion and analysis.” Cameco, February 20, 2025. Available at https://www.cameco.com/sites/default/files/documents/CCO%202024%20Q4%20MDA%20FS%20Notes.pdf.

Energy Intelligence. 2025. “Uranium: Draft Kazakh Law Pushes Long-Term Nationalization,” March 28, 2025. Available at https://www.energyintel.com/00000195-cdb7-d464-a7b7-dfbfd7b20000.

EurAsia Daily. 2025. “Канадскую добычу урана в Казахстане остановили: Cameco разочарована и удивлена.” [Canadian uranium mining in Kazakhstan stopped: Cameco disappointed and surprised.] EurAsia Daily, January 2, 2025. Available at https://eadaily.com/ru/news/2025/01/02/kanadskuyu-dobychu-urana-v-kazahstane-ostanovili-cameco-razocharovana-i-udivlena.

EurAsia Daily. 2024. “Урановый гигант из Канады: Транскаспийский маршрут в обход России оказался ненадежным.” [Uranium giant from Canada: Trans-Caspian route bypassing Russia proved unreliable.] EurAsia Daily, December 9, 2024. Available at

https://eadaily.com/ru/news/2024/12/09/uranovyy-gigant-iz-kanady-transkaspiyskiy-marshrut-v-obhod-rossii-okazalsya-nenadezhnym.

EUROSTAT. 2025. “Nuclear energy statistics.” Eurostat, January. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Nuclear_energy_statistics.

Gracelin, Baskaran. 2025. “Canadian Tariffs Will Undermine U.S. Minerals Security.” Center for Strategic & International Studies, January 29. Available at https://www.csis.org/analysis/canadian-tariffs-will-undermine-us-minerals-security .

Halef, Chris. 2025. “Ecology Action Centre criticizes N.S.’s bill to lift bans on fracking, uranium exploration.” City News, February 20, 2025. Available at https://halifax.citynews.ca/2025/02/20/ecology-action-centre-criticizes-nova-scotias-bill-to-lift-bans-on-fracking-uranium-exploration/.

Home, Andy. 2025. “Nuclear revival puts uranium back in the critical spotlight.” Mining.com, January 30, 2025. Available at https://www.mining.com/web/column-nuclear-revival-puts-uranium-back-in-the-critical-spotlight/.

Hunt, Paul-Alain. 2024. “Uranium Miners Say Australia to Miss Out on Nuclear Boom.” BNN Bloomberg, August 5, 2024. Available at https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/investing/2024/08/05/uranium-miners-say-australia-to-miss-out-on-boom-in-nuclear-fuel/ .

Interfax. 2024. “Kazatomprom diverted most uranium exports to bypass Russia in 2023.” Interfax, February 5, 2024. Available at https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/99086/ .

Karatayeva, Rimma. 2025. “«Казатомпром» остановил добычу урана к разочарованию канадцев: что происходит на месторождении Инкай.” [Kazatomprom Halts Uranium Mining to Canadian Disappointment: What’s Happening at Inkai Deposit.] ORDA, January 4, 2025. Available at https://orda.kz/kazatomprom-ostanovil-dobychu-urana-k-razocharovaniju-kanadcev-chto-proishodit-na-mestorozhdenii-inkaj-396461/.

Kar-Gupta, Sudip, Dominique Patton, and Bate Felix. 2024. “Orano warns of financial problems at Niger uranium plant.” Mining.com, November 15, 2024. Available at https://www.mining.com/web/orano-warns-of-financial-problems-at-niger-uranium-plant/.

- LS. 2018. “Казахстан снова обошел Канаду и Австралию по добыче урана.” [Kazakhstan again surpasses Canada and Australia in uranium production.] LS, July 30, 2018. Available at

https://lsm.kz/kazahstan-izvlek-39-dobytogo-v-mire-urana-v-2017-godu.

Mamyshev, Zhanbolat. 2025. “СП «Казатомпрома» с Канадой сорвало контракт. Чем это грозит.” [Kazatomprom’s joint venture with Canada has broken the contract. What is the threat?] Kursiv, February 14, 2025. Available at https://kz.kursiv.media/2025-02-14/zhnb-inkaiuraniumdown/.

Mann, Henry. 2025. “Uranium, Uranium, Uranium: The Strategic Investment for 2025 & Beyond.” Crux Investor, January 28, 2025. Available at https://www.cruxinvestor.com/posts/uranium-uranium-uranium-the-strategic-investment-for-2025-beyond.

Mining.com. 2025. “Cameco resumes uranium production at Inkai JV in Kazakhstan.” Mining.com, January 27, 2025. Available at https://www.mining.com/cameco-resumes-uranium-production-at-inkai-jv-in-kazakhstan/.

Njini, Felix. 2024. “Canada’s GoviEx Uranium’s stripped of Niger mining rights.” Reuters, July 5, 2024. Available at https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/canadas-goviex-uraniums-stripped-niger-mining-rights-2024-07-05/.

Oil price. 2024. “Canada Poised to Reclaim Top Spot as World’s Largest Uranium Producer.” Oil price, June 14. Available at https://oilprice.com/Alternative-Energy/Nuclear-Power/Canada-Poised-to-Reclaim-Top-Spot-as-Worlds-Largest-Uranium-Producer.html.

Patton, Dominique, Benjamin Mallet, and Felix Njini. 2024. “Orano says Niger has taken control of uranium mine.” Mining.com, December 4, 2024. Available at https://www.mining.com/web/orano-says-niger-has-taken-control-of-uranium-mine/.

Pavlich, Emile, and Else Kennedy. 2024. “Farmers and environmentalists raise concerns over uranium by-product from Victorian mine.” ABC News, November 7, 2024. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-11-08/victoria-uranium-mining-ban-loophole-mineral-sands/104473328.

Resource Works. 2024. “Putin’s uranium export restrictions are a gift for Canada.” Resource Works, October 9, 2024. Available at https://www.resourceworks.com/putin-uranium-canada.

RIA Novosti. 2023b. “‘Росатом’ планирует в 2029 году начать добычу урана в Намибии.” [“Rosatom Plans to Begin Uranium Mining in Namibia in 2029.] RIA Novosti, July 19, 2023. Available at https://ria.ru/20230719/uran-1884970829.html.

Saskatchewan Government. 2023. “Saskatchewan Second-Largest Global Producer of Uranium.” Saskatchevan.ca, June 13. Available at https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2023/june/13/saskatchewan-second-largest-global-producer-of-uranium.

Saskatchewan Government. 2024. “Saskatchewan Sees 306 Per Cent Jump in Uranium Exports to Europe.” Saskatchevan.ca, May 8, 2024. Available at https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2024/may/08/saskatchewan-sees-306-per-cent-jump-in-uranium-exports-to-europe.

Saskatchewan Government. 2025. “Critical Minerals.” Saskatchewan.ca, accessed April 3, 2025. Available at https://www.saskatchewan.ca/business/agriculture-natural-resources-and-industry/mineral-exploration-and-mining/critical-minerals.

Serikov, Daniyar. 2025b. “Канадская компания хочет убрать казахстанский уран с рынка США.” [Canadian company wants to remove Kazakh uranium from US market] Inbusiness.kz, January 28, 2025. Available at https://inbusiness.kz/ru/news/kanadskaya-kompaniya-hochet-ubrat-kazahstanskij-uran-s-rynka-ssha.

Serikov, Daniyar. 2025a. “Сколько “Росатом” заработал на продаже урановых активов Казахстана Китаю.” [How much did Rosatom earn from selling Kazakhstan’s uranium assets to China?] Inbusiness.kz, January 5, 2025. Available at https://inbusiness.kz/ru/news/skolko-rosatom-zarabotal-na-prodazhe-uranovyh-aktivov-kazahstana-kitayu.

Shi, Xunpeng, and Yifan Shen. 2023. “Bifurcation in the Critical Minerals Market Could Throw off the Global Energy Transition.” The Diplomat, November 7, 2023. Available at https://thediplomat.com/2023/11/bifurcation-in-the-critical-minerals-market-could-throw-off-the-global-energy-transition/.

Shivaprasad, Ashitha, Amy Lv, and Lewis Jackson. 2024. “FACTBOX What strategic mineral exports has China restricted?” Reuters, February 4, 2024. Available at https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-curbs-exports-strategic-minerals-2025-02-04/.

Siddi, Marco, and Kristiina Silvan. 2023. “Russia and Kazakhstan in the global nuclear sector. From uranium mining to energy diplomacy.” FIIA Briefing Paper, October 2023. Available at https://fiia.fi/en/publication/russia-and-kazakhstan-in-the-global-nuclear-sector#:~:text=Moreover%2C%20through%20its%20subsidiary%20TVEL,46%25%20of%20uranium%20enrichment%20capacity.

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2023a. “Chinese PSCs in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Anglophone Africa. Guardians of the Beld and Road Initiative, May 19, 2023. Jamestown Foundation. Available at https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-pscs-in-sub-saharan-africa-the-case-of-anglophone-africa/.

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2023b. “Chinese PSCs in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Cases of Francophone and Lusophone Africa.” Guardians of the Beld and Road Initiative, June 6, 2023. Jamestown Foundation. Available at https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-pscs-in-sub-saharan-africa-the-cases-of-francophone-and-lusophone-africa/.

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2024a. “Commodities as weapons: How Russia’s natural resources are fuelling its imperialistic aggression against the West.” Macdonald-Laurier Institute [MLI], October 31, 2024. Available at https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/commodities-as-weapons-how-russias-natural-resources-are-fuelling-its-imperialistic-aggression-against-the-west/.

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2024c. “Kazakhstan’s First NPP: Economics and Geopolitics.” The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, November 13, 2024. Available at https://cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13828-kazakhstans-first-npp-economics-and-geopolitics.html.

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2025b. “The Caspian Sea as an Emerging Energy Hub : Potentials and Limitations.” IFRI papers RUSSIE.EURASIE.VISIONS, No. 138, February 7, 2025. Available at https://www.ifri.org/en/papers/caspian-sea-emerging-energy-hub-potentials-and-limitations.

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2025a. “Unpacking the New Russia-Iran Treaty.” Gulf International Forum, 2025. Available at https://gulfif.org/unpacking-the-new-russia-iran-treaty/.

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2024b. “Western Powers in Pursuit of Kazakhstans Strategic Minerals: Prospects and Challenges.” The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, October 1, 2025. Available at https://cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13818-western-powers-in-pursuit-of-kazakhstans-strategic-minerals-prospects-and-challenges.html.

The Oregon Group. 2024. “Turning critical minerals into free range eggs. Can bifurcation of critical metal prices work?” The Oregon Group, June 25, 2024. Available at https://theoregongroup.substack.com/p/turning-critical-minerals-into-free.

Trend Economy. 2023. “Uranium or thorium ores and concentrates. Imports and Exports 2023.” Available at https://trendeconomy.com/data/commodity_h2/2612.

US Department of Energy. 2023. “At COP28, Countries Launch Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy Capacity by 2050, Recognizing the Key Role of Nuclear Energy in Reaching Net Zero.” Energy.gov, December 1, 2023. Available at https://www.energy.gov/articles/cop28-countries-launch-declaration-triple-nuclear-energy-capacity-2050-recognizing-key.

US Energy Information Administration. 2025. “U.S. nuclear generators import nearly all the uranium concentrate they use.” US Energy Information Administration, January 30, 2025. Available at https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=64444.

Volobuyev, Aleksandr, and Ilya Lakstygal. 2024. “«Росатом» вышел из уранового проекта в Казахстане.” [Rosatom Withdrew from Uranium Project in Kazakhstan.] Vedomosti, December 17, 2024. Available at https://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2024/12/17/1082031-rosatom-vishel-iz-uranovogo-proekta-v-kazahstane.

World Nuclear Association. 2024b. “Supply of Uranium.” World Nuclear Association, August 23, 2024. Available at https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/supply-of-uranium.

World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS). 2022. “Uranium ores and concentrates imports by country in 2022.” WITS 2022. Available at https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/ALL/year/2022/tradeflow/Imports/partner/WLD/product/261210.

World Nuclear Association. 2024a. “World Uranium Mining Production.” World Nuclear Association, May 16, 2024. Available at https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/mining-of-uranium/world-uranium-mining-production.

World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS). 2025. “Canada Natural uranium and its compounds, etc exports by country in 2022.” WITS accessed April 4, 2025. Available at https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/CAN/year/2022/tradeflow/Exports/partner/ALL/product/284410.

Yeoman, David. 2025. “The Future of Nuclear Energy: AI & Investment Trends.” Crux Investor, January 22, 2025. Available at https://www.cruxinvestor.com/posts/the-future-of-nuclear-energy-ai-investment-trends.