By Matthew Neapole, September 26, 2022

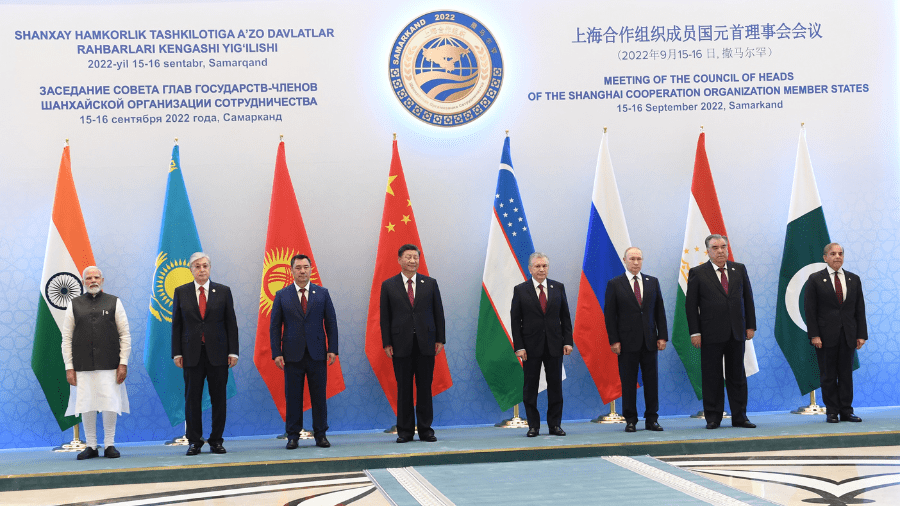

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s (SCO) Samarkand Summit of 2022 promised to be an important gathering, and it certainly delivered, hosting nearly 1000 journalists and the leaders of 13 countries. The Summit touched on various issues such as climate change, supply chains, as well as energy and food security. Furthermore, as expected of a gathering of this size, there was no shortage of developments in response to today’s uncertain international situation.

Various events, swirling in the backdrop, all highlighted a beleaguered Russia. We have the successful Ukrainian offensive, clearly seizing the initiative from Russia, and which has even sparked the necessity of calling for a partial Russian mobilization; a breakout in hostilities in the Caucasus between Armenia and Azerbaijan, but with no sending of troops from Russia; and a flare-up of simmering border tensions between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, both of which are SCO members. Added to this, allies such as Kazakhstan seem to be using the war to distance themselves from Moscow. All of this, in regions Russia traditionally considers within its “backyard.” A rocky start to ceremonies, indeed.

Xi’s journey to the west

A major highlight of the Samarkand SCO Summit was that this was Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first trip abroad since COVID-19, demonstrating the growing importance and centrality of the SCO to the agendas of its members and its largest driver. As some have pointed out, President Xi’s visit may also have been used to display that he feels safe enough in power to leave China, which he could not during the widespread lockdowns that paralysed China. However, this assessment may be premature, as will be laid out below.

President Xi made numerous comments. Avoiding direct mention of Ukraine, he nevertheless signalled continued support of Russia, saying “China will work with Russia to fulfill their responsibilities as major countries and play a leading role in injecting stability into a world of change and disorder… China will work with Russia to extend strong mutual support on issues concerning each other’s core interests.” This contrasts with Russia’s full-throated support for China on Taiwan issues, possibly demonstrating their power differential, or simply careful tact on China’s part.

President Xi also highlighted the need for SCO countries to be on the lookout for so-called “colour revolutions,” such as the Orange Revolution in Ukraine. These movements are viewed with suspicion by SCO members, who commonly believe them to be instigated by western, primarily American, backers. Furthermore, colour revolutions play a key role as a major threat in not just SCO documents, but also Chinese strategic thinking, representing as they do one of the Three Evils – Separatism, Extremism, and Terrorism.

Chinese outlets frequently label the unrest in Hong Kong as a possible colour revolution, and this unease may have been accelerated due to the extremely tense relations between Beijing and Washington over Taiwan. In the same vein, President Xi also spoke on the need to expand security cooperation, perhaps in light of these “revolutionary” threats, offering to train 2000 police, and urging stronger, more practical cooperation between SCO members.

President Xi’s comments signalled two points: that China-Russia relations are still strong and, perhaps more importantly, the possibility for unrest, which belies his continued worries of Western interference in domestic politics, possibly in reference to Hong Kong, other regions of China such as Xinjiang, or the SCO sphere at large. Perhaps President Xi’s base is not as solid, or his bid for another term as foregone a conclusion, as some surmise.

Putin’s eastern pivot

This was also a major international visit for President Putin, following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Yet it was likely not as successful as the Russian leader hoped. Broadly, President Putin aimed to demonstrate to outside observers and his domestic Russian audience that Russia is not as isolated as western powers would like it to be. President Putin was able to do this simply by attending, but it was also underlined by having bilaterals with other major powers, such as India and China, as well as announcing large deals, such as a major business delegation to Iran.

That being said, it likely did not go completely according to plan. For example, Indian Prime Minister Modi, in his opening remarks, told Putin that “this era is not an era of war,” which received a great deal of coverage in western media. To hear these remarks, particularly while Ukraine is in the midst of a successful counter-offensive, must have been less than ideal. However, these remarks could also be understood as common urgings towards a ceasefire, which India has consistently held to, and is a far cry from a “rebuke.”

Furthermore, PM Modi also was eager to “hear Russia’s side,” and the comments were preceded by an amicable meeting and were delivered and received calmly. India will continue to pursue an independent foreign policy, as it always has, and likely continue to have friendly ties with Russia. Indeed, India is importing deeply discounted Russian energy supplies at a record pace, underlining Indian reluctance to sever ties with Russia, even in the face of the West’s apprehension and its deepening ties to arrangements such as the Quad.

A similar interpretation is necessary when looking at President Putin’s statement about Ukraine to President Xi, when he said “we know you have concerns, which you have voiced many times.” This seems to imply tension in the so-called “No Limits Partnership.” However, these comments were also accompanied by praise for “Dear Comrade Xi’s… balanced approach.” The admission of worry on President Putin’s side were probably meant more as a sign of empathy and closeness than any sort of systematic problem in the Beijing-Moscow alignment.

Regardless, at the moment, Russia does not need direct support from China – which it is unlikely to receive anyway – and instead simply needs friendly markets for its resource-dependent economy. Indeed, that is also what the economic side of the SCO also provides.

The key takeaway is that analysis of Moscow’s interactions needs to be divorced from what we want to occur, and instead focus on how their relationship actually unfolds. For all intents and purposes, therefore, the SCO continues to provide a receptive outlet and audience to Russia, and a vehicle for Putin’s eastern pivot.

The SCO sphere continues to grow

Similarly, though experiencing unprecedented sanctions, Russia is not fully isolated; their narrative and rhetoric in particular have wide appeal to many states outside of the West, and the SCO amplifies it. Iran is one such enthusiastic new member for the SCO – they are expected to formally join by April 2023, finalizing the lengthy accession procedures.

Turkish President Erdogan, despite providing support to Ukraine, not to mention being a NATO member itself, was invited to the SCO Summit by President Putin. There, President Erdogan signalled eagerness to join the SCO, saying that “Our relationship with these countries will be moved to a much different position with this step.” Pressed on this, he doubled down by explicitly saying that membership was a direct target. This follows his 2016 comments when he compared SCO membership to that of the European Union (EU), demonstrating his long-term interest in joining the SCO; a strong belief in its economic clout; and also a deep disillusionment with the EU and the West – a common sentiment among SCO members.

We also see interest of other parties outside of the western bubble. Specifically, the Samarkand Declaration officially announced that three more states will become Dialogue Partners: Qatar, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. This is commonly understood as a step towards eventual membership. Furthermore, Belarus, a close ally of Russia, has received public (and expected) Russian support at the Samarkand Summit for joining as a full member, and its membership was also raised in the Samarkand Declaration itself.

These developments exhibit the SCO’s dogged devotion to a principle of multipolarity in world politics. Another effort is popularization national currencies in payments, which was also emphasized in the Samarkand Declaration. These two characteristics, combined with the joining of Belarus, could be seen as rare outright “wins” for Moscow in the SCO. By joining together with other like-minded countries, many states most likely believe that their interests will be highlighted, or at least their regimes will experience less outside intervention, perceived or real. Indeed, reasserting their belief in non-intervention and “multicultural and civilizational diversity” was also highlighted – a different wording for a rejection of western universalisms. Simply put, the SCO’s messaging and rhetoric does not seem to be weakening, but instead growing.

Taken together, this year’s SCO Summit was unlike many others before it, especially considering the current, tense, international atmosphere. That the leaders still converged and expressed at least tacit support of Russia, demonstrates the shift in power alignment in the world. Along with recent SCO Summits, the SCO Samarkand Summit may be the norm going forward. While the SCO consistently advocates a policy of non-alignment and non-targeting of third parties, it is increasingly made up of states that have deep, unsettled problems with the West at large: all striving “for a closer community of destiny.”

Matthew Neapole holds an MA in International Relations from the University of Groningen and is particularly drawn to the dynamic Indo-Pacific, the evolving Japanese security situation, as well as China’s strategic policy. He lived for nearly a decade in Japan, as well as in the Netherlands and Belgium. The views expressed are his own, and do not reflect those of any employment he currently holds.