This article originally appeared in the Toronto Star.

By Ken Coates and Karen Restoule, November 6, 2024

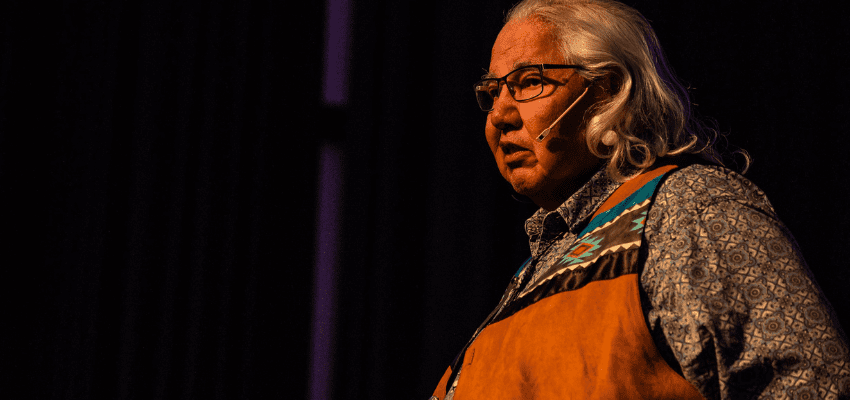

Canada just lost one of its most important citizens. The death of Murray Sinclair has already generated dozens of testimonials and fond remembrances for an individual who transformed Indigenous-newcomer relations in Canada and who worked extraordinarily hard to get the country on a path to sustainable reconciliation.

The Canada of Murray Sinclair’s youth was, for Indigenous Peoples, a harsh and unforgiving place.

In waves of paternalism and government intervention, Indigenous Peoples were moved off their lands, onto reserves or into the cities and, far too often, into the courts and prisons.

Together with the Donald Marshall Jr. inquiry in Nova Scotia, Justice Sinclair’s report on racism in the Manitoba judiciary exposed the brutal inequalities of Canadian law and held a mirror up to the ugliness of the treatment of Indigenous Peoples in Canada’s legal system.

Although he had many good reasons to be angry and dismissive of non-Indigenous people, Sinclair opted for a different approach. He was optimistic throughout his life, using the identification of serious problems as the starting point for a constructive and positive journey and not as a foundation for protest and frustration.

He heard thousands of stories, many of them desperately sad and deeply problematic. He stood in solidarity with the victims of past injustices and sought to turn their suffering into a tapestry that would explain the pain and resilience of Indigenous Peoples. He sought to build a pathway toward mutual understanding and healing for future generations.

The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which he chaired, embodies the depth of his wisdom and the power of his compassion and has become an international manual on how to recognize and overcome the mistreatment and marginalization of Indigenous Peoples.

That “reconciliation” entered the national vocabulary is a testament to his gentle persuasiveness and the thoroughness with which he laid the foundation for sustained and meaningful collective action. Sinclair knew, too well, the causes and the consequences of Indigenous despair but he chose to live his life with optimism and an unbending belief that Canada could do better.

But his impact went beyond even the monumental achievement of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report. He emerged as a leader for all who call Canada home, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike. Unlike so many elected officials caught in partisan games, he worked to rebuild a sense of nationhood grounded in respect, understanding, and mutual recognition.

His vision for a reconciled Canada sought to unite the strengths of Indigenous Nations and Canadian ideals, creating a path toward a future where the best of both worlds could flourish together. No other leader, whether elected or not, has matched the depth of his commitment to this vision.

That the country has made some progress in bridging the divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples is due, in no small part, to his leadership and passion; the nation can honour his life by doubling our efforts to produce true and lasting reconciliation and to build a society that reflects the remarkable quality of his life and the transcendent power of his vision.

Ken Coates is the director of indigenous affairs at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Karen Restoule is vice president at Crestview Strategy and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. She is Ojibwe from Dokis First Nation.