By Joshua Krasna

April 9, 2024

Since November 2023, Yemen’s Ansar Allah militia – known as the Houthis, after its founding family – has been attacking merchant shipping in the Bab al-Mandab Strait.

The trigger for this was solidarity with the population of Gaza though, as we shall discuss, the underlying drivers are more complex; in any case, the attacks and their motivations have expanded as the United States and the United Kingdom responded to the Houthi actions with military force.

The Houthi attacks on shipping have dramatically reduced trade through the strait as well as through the Suez Canal, on the other end of the Red Sea. This has disrupted and largely displaced some 12 percent of world trade (30 percent of world container trade) and has had worldwide economic effects.

The Houthis have thus internationalized the current conflict in the Middle East as no other player has done; they relish their new-found influence and will probably continue to wield it in the future.

The Conflict in the Red Sea

On October 7, 2023, Hamas forces launched a surprise attack in southwestern Israel, raping, torturing, murdering, and kidnapping Israeli civilians. In response, Israel launched a counterattack on the Gaza Strip to free the hostages and eliminate the Hamas threat in the Palestinian territory.

Starting in late October, as the Israeli military operation unfolded, the Houthis – who are in de facto control of northwest Yemen, including the country’s capital, Sana’a – began sporadically firing missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) towards southern Israel. These have almost all been intercepted by Israeli air defence forces and by American and later, allied warships in the Red Sea. In November, the Houthis began attacking ships in and near the Red Sea, initially against vessels with connections to Israel (sometimes extremely tenuous, and apparently extracted from imprecise or outdated open sources), and after the intervention of US and UK, against their ships as well; in actuality, the attacks have been indiscriminate and struck ships of many nationalities. Most of the attacks have been by UAVs and anti-ship missiles, with occasional attacks by small armed vessels.

As the world’s largest navy and largest trading power, the US sees itself as the protector and guarantor of freedom of navigation worldwide. On December 18, 2023, it launched Operation Prosperity Guardian (Lagrone 2023) to protect Red Sea shipping. A handful of Canadian staff officers are participating in the operation.

Many US allies, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, have demurred from joining the force, and most have not sent ships[1] (Bahrain is the only Arab state to have openly joined). Other states have sent ships to the region (including the European Union, Chinese, and Indian task forces) but not as part of the American-led effort.

Most of the attempted attacks on shipping have been intercepted. Since January 11, 2024, the US and UK have carried out direct attacks against Houthi targets in Yemen (via Operation Poseidon Archer) (Shelbourne and Lagrone 2024). On January 10, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2722 (UN 2024) calling on the Houthis to stop attacks on ships in the Red Sea (China and Russia abstained).

Economic effects

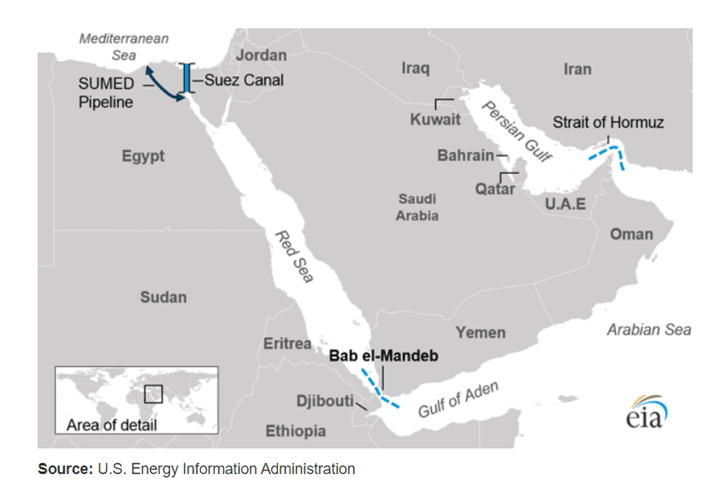

The geoeconomic impact of the Houthi actions has been severe. It has been one of the largest disruptions and dislocations of global trade in recent decades. The Bab al-Mandab serves as the southern gateway to the Suez Canal, through which some 20,000 ships transit annually, carrying 30 percent of world container trade, 10-12 percent of world trade by volume, and 9 percent of world oil trade (Garcia-Vazquez 2024). It is critical to trade between Asia and Europe and the Mediterranean (also, to an extent, the US East Coast).

In 2023, the canal carried record volumes, largely due to Russian oil shipments to Asia and the Persian (also known as Arabian) Gulf; these have dropped by half. Notwithstanding the US and allied efforts, most civilian ships, including most of the largest international shipping companies, have chosen to avoid the Red Sea (and thus, the Suez Canal), due to danger and to higher risk premiums and security costs (MEES 1 2023). War risk insurance premiums for vessels traversing the Red Sea have risen from 0.07 percent to 0.7–1 percent of the value of a ship’s cargo (Longley 2024). Shipping through the Bab al-Mandab has declined by close to 60 percent compared to six months ago (Lee 2024).

Shippers now send their cargoes around the Cape of Good Hope and up the western coast of Africa, extending the trip significantly: the route from Asia to Europe adds 3200 nautical miles and 7 to 12 days (longer for tankers) to the trip. The longer route also raises crew and fuel costs, as well as tying up ships for longer, thus tightening the global supply of vessels available for shipping. This lack of capacity has led to “knock-on” declines of over 5 percent in maritime trade on trans-Pacific routes as well. In addition, the need for greater speed on the longer trips to make up time, has led to increased fuel consumption and higher emissions (Zhang et al, 2024).

In March 2024, the cost to ship a standard 40-foot (12.2-metre) container from Asia to Europe, including recently added surcharges, was US$4500 (Kiel, 2024), some three times the rate charged just before the Red Sea diversions. Ship tonnage entering the Gulf of Aden declined by over 70 per cent between the first half of December 2023 and the first half of February 2024; meanwhile, vessel tonnage passing around the Cape of Good Hope increased by 60 per cent (UNCTAD, 2024).

The delays and higher costs have significant follow-on effects on supply chains and inventory management, and on the profitability of the firms importing and exporting, especially from Europe to Asia. This may have possible inflationary repercussions if the added costs are passed on to consumers. The disruption this has caused to world trade is even more pronounced as it coincides with disruption of maritime trade through the Panama Canal (reduced by half, due to drought), which accounts for some 5 percent of world trade, and occurs in a global market still adapting to changes caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its impact on Black Sea shipping (UNCTAD 2024).

The impact of the Red Sea crisis seems to be felt most seriously by European firms and by Asian countries with significant trade with Europe and the East Coast of the U.S, especially China (which accounts for more than 21 percent of all EU imports) and India (12 percent of whose total goods exports pass through the Red Sea region, on their way to Europe) (Clynch 2024 and Denamiel et al. 2024). Forty percent of trade between Europe and Asia usually goes through the Suez Canal and Red Sea (Babb 2024).

China has called for “a halt to the harassment and attacks on civilian ships and for the maintenance of the smooth flow of global industrial and supply chains and the international trade order” (Reuters 2024). Chinese ships are apparently still using the Red Sea route, with reports that they are escorted by Chinese warships deployed in recent months to the region (Babb 2024).

Some ships, especially Russian vessels, attempt to broadcast their nationality, and their lack of ties with Israel, as they continue using the Red Sea route (Longley and Wittels, 2024). Russia and China have reportedly reached agreement with the Houthis that their ships can sail through the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden without being attacked; in exchange, the two countries may provide political support to the Houthis in bodies such as the United Nations Security Council (Dagher and Hatem 2024 and TASS 2024). In addition, they may feel that their good relations with Iran may inoculate them. However, the Houthis’ ability to discriminate between targets is limited (a few ships with Russian and Chinese links have been targeted), and this is probably the reason that China’s state-owned COSCO container line has suspended shipping through the Red Sea (Clynch 2024).

The trade and economy of the ostensible target of the Houthi efforts, Israel, has suffered significantly from the war. Many ships (and flights) refrain from visiting Israeli ports: Container traffic has declined by some 25 percent (Binyamin 2024). This is due not only to Houthi action in the Red Sea (mostly affecting the Asia trade), but also to curtailment of the Eastern Mediterranean trade due to the Gaza conflict and tension between Israel and Lebanon. The port of Eilat, at the northeastern tip of the Red Sea, has been almost entirely shut down due to the disruptions of Red Sea trade, but before the October 7 attacks by Hamas, it accounted for some 5 percent of Israeli trade.

Most Severe Impact is on Egypt

Egypt is the country suffering most from the disruption in the Red Sea. It is experiencing an extreme economic crisis due to deep structural problems, massive deficits, and crippling debt (Stevenson 2024). The recent promise of US$35 billion in Emirati funding for a massive development project on its Mediterranean coast, an US$8 billion loan from the IMF (enabled by devaluation of the pound by 38 percent), a US$7.4 billion financial aid package from the EU, and $US6 billion from the World Bank, have temporarily distanced the wolf from the door.

The Suez Canal – the third greater source of foreign currency, after remittances and tourism – brings in over US$9 billion a year in transit fees, equivalent to 2.3 percent of GDP in 2023 (El-Wardany and Magdy 2024); January 2024 receipts were half those of a year before, despite Egypt’s raising fees to offset falling receipts. In addition, the rising cost of imports, including raw materials, and greater turnaround time has impacted Egyptian industries (Dutton 2024), and may stoke already high inflation.

However, Egypt has shown no indication of willingness to use force in the Red Sea in the current crisis. This is despite having defined the sub-region in the past as of strategic interest and even inaugurating a naval and air base in Berenice in 2020, with the express purpose of “protecting and securing the Egyptian southern coasts … confronting security challenges within the Red Sea … [and] safeguarding global navigation through the axis of movement from the Red Sea to the Suez Canal and the related economic regions” (Republic of Egypt 2024). Its leadership is probably concerned, like those of Saudi Arabia and UAE, about taking actions which could be perceived as helping Israel, even if indirectly.

Red Sea coastal states are also suffering major disruptions in seaborne trade (Thompson 2024). Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, and Djibouti, for example, rely heavily on grain imports from the EU, Russia, and Ukraine: all their seaborne trade transits the Bab al-Mandab or the Suez Canal (Anyanzwa 2024). Jordan, whose seaborne imports and potash exports move through its only port in Aqaba near Eilat, which also serves as a regional container hub, is also expected to suffer trade dislocations, though it has an alternative land-marine route from Egypt (Anderson, 2023).

Effect on Energy Markets

The effect of the closure of the Red Sea and the extension of shipping routes on global energy prices, after an initial surge, has been somewhat muted by relatively stable global gas and oil prices due to mild winters in Europe, economic slowdown in China, booming US (now the world’s largest producer and exporter) and Canadian production, and the emergence of new Latin American producers. BP, Shell, and Qatar Energy have suspended energy shipments through the Red Sea (Faucon and Strasburg 2024). This last is significant, as Qatari liquified natural gas (LNG) was 5 percent of EU gas imports (and 13 percent of LNG imports) last year.

Regarding the Middle East producers, Saudi Arabia alone has the capability of moving oil via internal pipelines to its Red Sea ports north of the Bab al-Mandab (at Yanbu and Muajjiz) and exporting through the SUMED pipeline or the Suez Canal. The ability to export crude oil from its Red Sea terminals means that Aramco is well placed to capitalize on the current shipping disruption (MEES 2 2024).

Saudi Arabia also still sends some shipments from its Persian Gulf coast through the Bab al-Mandab: it may be less worried about Houthi attacks due to its ongoing détente with Iran, and peace talks with the Houthis. A Houthi spokesperson said on January 19 that that the group has no plans to target Saudi Arabia and the UAE (MEES 3 2024). Persian Gulf oil producers with clients primarily in Asia rather than Europe (such as Kuwait and UAE) have so far been largely insulated from the economic impact of the Houthi attacks. The most exposed of the Middle East producers is Iraq, approximately one quarter of whose oil exports transit the Bab al-Mandab, since the route through Turkey to the Mediterranean has been closed since March 2023 (MEES 4 2023, see also Krasna 2023).

Russian oil carried by both its official carrier and its “ghost fleet” continues to flow through the Bab al-Mandab to its customers in India (whose largest supplier is Russia) and China (whence most of the Russian oil arrives from Russia’s Asian ports), as well as to traders in the Persian Gulf. About 1.7 million barrels a day of Russian crude, or just under a half of the nation’s total seaborne exports, continue to transit the danger zone (Bloomberg 2024). Rerouting the shipments around Africa would more than double Russia-India journey times and reduce the already-squeezed profit margins on cut-rate Russian crude exports, as well as the availability of tankers. This gives them a higher tolerance of risk.

Houthi Motivations and Strategy[2]

The Houthis’ attacks in the Red Sea are a manifestation of their ideology, rooted in Islamic fundamentalism, fierce nationalism, and hatred of Jews, Israel, and the United States (Al-Dawsari 2024). It is also based on their close identification with the Iranian-led “Axis of Resistance,” for them not only an ideological alignment, but also a force multiplier. However, the Houthis are not an Iranian puppet: they have their own ideological and nationalist agenda and operate with relative autonomy.

Houthi military-technological capabilities have jumped dramatically in recent years, as Iran has armed them as part of the Axis of Resistance and as an instrument and ally in creating the ability to threaten Western, Israeli, and moderate Arab interests throughout the region (e.g. the repeated attacks on Saudi Arabia, and the attack on Abu Dhabi in January 2022). The crisis in Gaza gave the Houthis an opportunity to display the relevance of these new capabilities, but their strategic objectives are far beyond Gaza.

The Houthis are the dominant political actor in Yemen and will be so for the foreseeable future. The use of their newfound military power to impose themselves on the global scene may be driven primarily by the Houthis’ desire to use their direct championing of the Palestinian cause (taking risks no one else is willing to), and the American-led attacks on them, to shore up and consolidate their domestic position, and divert attention from governance and economic failures.

This reintroduces an external threat to help rally Yemenis around the (Houthi) flag. In addition, they wish to compel the region and the international community to acknowledge and engage with them, and thus promote their agenda of achieving international recognition and legitimacy as the ruling authority in Yemen (in much the same way the Taliban did so in Afghanistan, over two decades). Their action has also afforded them massive appeal (“street cred”) in the Arab and Muslim world, which could perhaps be used to pressure adversaries.

Iran is attempting to preserve a cushion of deniability regarding connection with the Houthi attacks, though the latter have clearly been enabled by technology and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) advisors from Tehran, and Iran itself has carried out aggressive activity during the crisis.

The Houthis are thought to receive intelligence on shipping from Iran’s surveillance ships in the Red Sea; the US reportedly carried out a cyberattack on such a ship in February (Reuters 2024a). In addition, Iran has in the Indian Ocean attacked one ship with a UAV, and seized another ship, which had seized from it in the past (US Navy Central Command 2024). Several countries, reportedly including the United States and India, have approached Iran to use its influence to stop the Houthi attacks (Fassihi and Schmitt 2024, and Economic Times 2024).

Iran seems to have concluded that the Houthis’ experiment in the Red Sea has been so successful that it may bear repeating in the Mediterranean. “They shall soon await the closure of the Mediterranean Sea, [the Strait of] Gibraltar and other waterways,” Brigadier General Mohammad Reza Naqdi, the coordinating commander of IRGC, told Iranian media on December 23, 2023, apparently referring to the international community (Reuters 2023).

Prognosis

Now that the Houthis have demonstrated to the world and to themselves their capacity to disrupt global shipping, and thus re-positioned themselves from a strategic backwater to an influential geopolitical actor, it is anticipated that the current actions will serve as a precedent. They will continue to leverage that capability, perhaps when other members of the “resistance” camp are threatened, when negotiations with Saudi Arabia hit snags, or for economic advantage.

This is especially true as they do not seem to be much affected by the military efforts by the US and others to punish and deter them from their actions, though these have allowed the Houthis to somewhat shift the rationale for their actions. This means inter alia that the Houthi threats to shipping in the Bab al-Mandab are not expected to end when the Gaza conflict does. It is not at all clear even whether a temporary ceasefire in Gaza (for which they well may take credit) will lead to one in the Red Sea.

Maritime security in the Red Sea will be under lasting, proven threat for the foreseeable future as long as the Houthis continue to have access to Iranian technology and re-supply. The longer-term, persistent Houthi threats to the Red Sea’s attractiveness as a shipping corridor could influence Gulf states’ efforts to solidify their centrality to international trade and supply chains. The demonstration of the ease of closing a key maritime chokepoint, by occasional attacks and allowing insurance and business calculations to do the rest, is quite concerning regarding the Straits of Hormuz (though that would not appear to be in Iran’s interest, as it harms its oil exports).

The Red Sea crisis could potentially erode Europe’s recent developing dependence on Middle East energy shipments, as they wean of their decades-old addiction to cheap Russian gas and oil. Concern with maritime chokepoints can benefit existing LNG suppliers, which do not need to transit problematical areas, especially the U.S, the largest supplier of LNG to the EU.

Canadian gas could theoretically be in greater demand as well, though the lack of LNG gas export infrastructure on the Atlantic coast means that Canada is unfortunately unprepared to capitalize on the opportunity.

The increased risk will increase the attractiveness of close-at-hand Mediterranean gas: while North African sources are already well developed and integrated into the European gas infrastructure, there is still potential for increased Eastern Mediterranean – Israeli, Egyptian, and Cypriot – gas supply to Europe. Interest in this should develop as the immediate chilling effects of the Israel-Hamas war and the tension in Lebanon recede.

The near closure of the Red Sea has sharpened awareness of the danger maritime chokepoints can pose for international trade and highlights the importance of ground and multi-modal routes that avoid chokepoints. This has in the view of some experts (see, e.g., Abdulkhaleq 2023, and Khanna 2024) heightened the importance of projects like China’s BRI, which includes a significant intercontinental rail component, and the India – Middle East – Europe Economic Corridor (White House 2023), avoiding the Bab al-Mandab and the Suez Canal; UAE and India signed an agreement on the corridor (which will include rail links) on February 13, 2024 (Lucente 2024).

There have been reports of some Israel-bound goods downloaded in Bahrain and Dubai and sent by truck through Saudi Arabia; these reports have been denied, probably due to the “optical” sensitivity in Jordan of trade through Israel (though goods have been transshipped to and through Israel for many years, even before the Abraham Accords). There has reportedly been a marked increase in shipments from Asia to Europe using the state-controlled Russian rail system (Wright 2024); it is also quite possible that China will increase its use of the Northern Sea route through the Arctic, which Russia is promoting, as well (Perkins 2023). Air freight volumes through the Persian Gulf have also reportedly surged in early 2024, as suppliers try to compensate for the changes in seaborne trade. There may also be increased interest in overland pipelines bypassing the Red Sea (Wendel 2024).

About the author

Joshua Krasna is a retired Israeli senior government analyst and diplomat. He teaches at NYU’s Center for Global Affairs and the University of Ottawa’s Professional Development Institute. He is the director of the Center for Emerging Energy Politics in the Middle East at Philadelphia’s Foreign Policy Research Institute, and a senior researcher at the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African studies in Tel Aviv.

References

Abdulla, Abdulkhaleq. “اصبح مشروع هذا الممر الاقتصادي الذي يربط اسيا باوروبا عبر موانئ الإمارات مطلوبا وضروريا وحيويا اكثر من أي وقت آخر ويجب البدء فيه سريعا وعاجلا، فكل $ استثمار في هذا الممر التجاري المستقبلي في محله في ضوء تزايد تهديد الحوثي للملاحة في باب المندب والبحر الاحمر وبحر العرب. Pic.Twitter.Com/Lfatzfsh9h.” Twitter, December 19, 2023. Available at https://twitter.com/Abdulkhaleq_UAE/status/1737160849721045143.

al-Dawsari, Nadwa. “The Ideological Underpinnings of the Houthis’ Red Sea Attacks.” Middle East Institute, January 22, 2024. Available at https://www.mei.edu/publications/ideological-underpinnings-houthis-red-sea-attacks?s=09.

Anderson, Guy. “Troubled Waters: Impact of the Red Sea Crisis on the Economies of Egypt, Israel, and Jordan.” Janes Intelligence Review, January 10, 2024. Available at https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/troubled-waters-impact-of-the-red-sea-crisis-on-the-economies-of-egypt-israel-and-jordan.

Anyanzwa, James. “East Africa Braces for Further Rise in Food, Fuel Prices over Red Sea Crisis.” The East African, February 4, 2024. Available at https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/east-africa-braces-for-further-rise-in-food-fuel-prices-over-red-sea-crisis-4512884.

Babb, Carla. “Where Is China in the Red Sea Crisis?” Voice of America, March 1, 2024. Available at https://www.voanews.com/a/where-is-china-in-the-red-sea-crisis-/7510435.html.

Barrington, Lisa. “UAE Says It Has Stopped Taking Part in US-Led Gulf Maritime Coalition.” Reuters, May 31, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/uae-says-it-withdrew-us-led-maritime-coalition-two-months-ago-2023-05-31/.

Binyamin, Idan. “December’s Containers Have Arrived, but Port Activity Is Far from Recovered [Hebrew].” The Marker, February 20, 2024. Available at https://www.themarker.com/dynamo/2024-02-20/ty-article/.premium/0000018d-c694-d186-a9cd-f69dc75b0000.

Bloomberg. “Russian Oil Still Going Through Red Sea Despite Houthi Missiles.” January 16, 2024. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-16/houthi-red-sea-attacks-fail-to-deter-russian-oil-carriers.

Clynch, Harry. “How Red Sea Tension Is Hurting China’s Auto Industry in EU, US.” Al-Monitor, January 18, 2024. Available at https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2024/01/how-red-sea-tension-hurting-chinas-auto-industry-eu-us.

Dagher, Sam and Mohammed Hatem. “Yemen’s Houthis Tell China, Russia Their Ships Won’t Be Targeted.” Bloomberg.com, March 21, 2024. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-03-21/china-russia-reach-agreement-with-yemen-s-houthis-on-red-sea-ships.

Denamiel, Thibault, Matthew Schleich, William Alan Reinsch, and Will Todman. “The Global Economic Consequences of the Attacks on Red Sea Shipping Lanes.” CSIS, January 22, 2024. Available at https://www.csis.org/analysis/global-economic-consequences-attacks-red-sea-shipping-lanes.

Dutton, Jack. “How Red Sea Crisis Is Battering Egypt’s Manufacturing, Textile Industries.” Al-Monitor, February 22, 2024. Available at https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2024/02/how-red-sea-crisis-battering-egypts-manufacturing-textile-industries.

Economic Times. “Business Heads Fear Lasting Bottlenecks from Red Sea Crisis.” Available at The Economic Times, January 17, 2024. Available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/business/business-heads-fear-lasting-bottlenecks-from-red-sea-crisis/articleshow/106936429.cms?from=mdr.

Fassihi, Farnaz and Eric Schmitt. “Iran and U.S. Held Secret Talks on Proxy Attacks and Cease-Fire.” The New York Times, March 15, 2024. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/15/world/middleeast/iran-us-secret-talks.html.

Faucon, Benoit and Jenny Strasburg. “WSJ News Exclusive | Shell Suspends Red Sea Shipments amid Fears of More Houthi Attacks.” Wall Street Journal, January 16, 2024. https://www.wsj.com/world/middle-east/shell-suspends-red-sea-shipments-amid-fears-of-more-houthi-attacks-c7fa936d.

Garcia-Vazquez, Gilberto. “Suez Canal: Engineering Marvel and Crisis Chokepoint.” The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Accessed March 22, 2024. https://oec.world/en/blog/suez-canal.

Khanna, Parag. “The Red Sea Crisis Proves China Was Ahead of the Curve.” Foreign Policy, January 20, 2024. Available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/20/url-red-sea-houthis-china-belt-road-suez-trade-corridors/.

Kiel Institute. “Kiel Trade Indicator: Renewed Slump of Ship Transits in the Red Sea after Slight Stabilization.” March 11, 2024. Available at https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/news/renewed-slump-of-ship-transits-in-the-red-sea-after-slight-stabilization/.

Krasna, Joshua. “Autonomy Curbed? Kurdish Oil Exports Hit Snags from Turkey and Baghdad.” Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, July 3, 2023. Available at https://dayan.org/content/autonomy-curbed-kurdish-oil-exports-hit-snags-turkey-and-baghdad.

LaGrone, Sam. “‘Operation Prosperity Guardian’ Set to Protect Ships in the Red Sea, Carrier Ike in Gulf of Aden.” USNI News, December 19, 2023. https://news.usni.org/2023/12/18/operation-prosperity-guardian-set-to-protect-ships-in-the-red-sea-carrier-ike-in-gulf-of-aden.

Lucente, Adam. “How Critical Is UAE-India Trade Corridor in Countering China & Red Sea Tensions?” Al-Monitor, February 15, 2024. Available at https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2024/02/how-critical-uae-india-trade-corridor-countering-china-red-sea-tensions.

Lee, Julian. “Ships Keep Running Red Sea Gauntlet after US Warnings.” Bloomberg.com, January 16, 2024. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-16/ships-keep-running-red-sea-gauntlet-after-us-warnings.

Longley, Alex and Jack Wittels. “More Ships Flag No Link with Israel as Red Sea Turmoil Continues.” Bloomberg.com, January 17, 2024. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-17/more-ships-flag-no-link-with-israel-as-red-sea-turmoil-continues.

Longley, Alex. “Red Sea: Soaring Insurance Bills Adding to Mounting Trade Chaos.” Bloomberg.com, January 15, 2024. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-15/add-soaring-insurance-bills-to-mounting-red-sea-trade-chaos.

MEES 1. “Shipping Firms Avoid Red Sea As Yemen’s Houthis Ramp Up Attacks,” Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 66. No. 51/52, 22 December 2023.

MEES 2, “Aramco Bypasses Houthi Threat with Yanbu Arab Heavy-To-Europe Shipments,” Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 67, No. 8, 23 February 2024.

MEES 3, “Saudi Tankers Risk Bab al-Mandab Crossing To Supply Domestic Markets,” Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 67, No. 3, 19 January 2024.

MEES 4, “Yemen’s Breakthrough Truce Threatened By Houthi Military Attacks,” Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 66. No. 48, 1 December 2023.

Perkins, Robert. “Russia’s Arctic Oil Exports Surge but Risks Still Hamper New Trade Route.” S&P Global Commodity Insights, November 29, 2023. Available at https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/112923-russias-arctic-oil-exports-surge-but-risks-still-hamper-new-trade-route.

Republic of Egypt Presidency. “Berenice Military Base.” Accessed March 21, 2024. Available at https://www.presidency.eg/en/المشاريع-القومية/قاعدة-برنيس-العسكرية.

Reuters. 2024. “Egypt, China Stress Priority of Safety, Security of Red Sea …,” January 14, 2024. Available at https://www.reuters.com/world/egypt-china-stress-priority-safety-security-navigation-red-sea-joint-statement-2024-01-14/.

Reuters. 2024a. “US Conducted Cyberattack on Suspected Iranian Spy Ship, NBC News ….” February 15, 2024. Available at https://www.reuters.com/world/us-conducted-cyberattack-suspected-iranian-spy-ship-nbc-news-2024-02-15/.

Reuters. 2023. “Iran Threatens Mediterranean Closure over Gaza, without Saying ….” December 23, 2023. Available at https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iran-threatens-mediterranean-closure-over-gaza-without-saying-how-2023-12-23/.

Shelbourne, Mallory and Sam Lagrone. “Major U.S., U.K. Strike Hits Houthi Missile, Drone Infrastructure.” USNI News, January 23, 2024. https://news.usni.org/2024/01/22/u-s-u-k-launch-major-strike-missions-on-houthi-missile-drone-infrastructure.

Stevenson, Peter. “Egypt’s Financial Woes Mount: Record Debt & Deficit as Devaluation Looms.” MEES, December 15, 2024. Available at https://www.mees.com/2023/12/15/economics-finance/egypts-financial-woes-mount-record-debt-deficit-as-devaluation-looms/699709f0-9b53-11ee-8d0e-e743e632a27f.

TASS, “Senior Houthi Official Promises Safe Passage via Red Sea to Russian, Chinese Ships.” January 19, 2024. Available at https://tass.com/world/1734473.

Thompson, Felix. “UN: Red Sea and Panama Canal Disruptions Causing Global Trade Upheaval.” Global Trade Review (GTR), March 6, 2024. Available at https://www.gtreview.com/news/global/un-red-sea-and-panama-canal-disruptions-causing-global-trade-upheaval/.

UN, January 10, 2024. Available at https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n24/001/86/pdf/n2400186.pdf?token=BSgVGijd2I27tWx9eM&fe=true.

UNCTAD. “Navigating Troubled Waters: Impact to Global Trade of Disruption of Shipping Routes in the Red Sea, Black Sea and Panama Canal.” February 22, 2024. Available at https://unctad.org/publication/navigating-troubled-waters-impact-global-trade-disruption-shipping-routes-red-sea-black.

United States Navy Central Command. “Iran Attacks and Seizes Merchant Shipping Vessel.” January 11, 2024. https://www.cusnc.navy.mil/Media/News/Display/Article/3643545/iran-attacks-and-seizes-merchant-shipping-vessel/.

Wardany, Salma El and Mirette Magdy. “Red Sea Chaos Leaves Egypt to Grapple with Dwindling Suez Canal Revenue.” Bloomberg.com, January 17, 2024. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-17/red-sea-chaos-leaves-egypt-to-grapple-with-dwindling-suez-canal-revenue.

Wendel, Samuel (Wendel 1). “How Red Sea Attacks Could Rewire Middle East Trade and Economic Cooperation.” Al-Monitor, March 3, 2024. Available at https://www.al-monitor.com/pro/memos/how-red-sea-attacks-could-rewire-middle-east-trade-and-economic-cooperation?utm_medium=email.

Wendel, Samuel (Wendel 2). “Middle East Economies Navigate Treacherous Straits as Gaza War Infects Red Sea.” Al-Monitor, January 6, 2024. Available at https://www.al-monitor.com/pro/memos/middle-east-economies-navigate-treacherous-straits-gaza-war-infects-red-sea.

The White House. “Memorandum of Understanding on the Principles of an India – Middle East – Europe Economic Corridor.” September 9, 2023. Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/09/09/memorandum-of-understanding-on-the-principles-of-an-india-middle-east-europe-economic-corridor/.

Wright, Robert. “Russia’s Rail Boosted by Demand to Move Goods to Europe after Red Sea Attacks.” Financial Times, March 9, 2024. Available at https://www.ft.com/content/4c334d94-66e6-49f4-9256-b30b4ebca984.

Zhang, Zera, Rico van Leuken, and Lars Karlsson. “Charting the Course: How the Shipping Industry Is Adapting to Tensions in the Red Sea.” World Economic Forum, February 23, 2024. Available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/02/red-sea-crisis-global-shipping-industry-adapting-maersk/.

[1] In May, the UAE stopped taking part the previous military coalition that the United States established to protect shipping in the Persian Gulf, explaining that it preferred diplomatic solutions to military ones (Barrington 2023). Both these states may well prefer not to participate in the current military coalition, to prevent possible resumption of Houthi attacks on targets in their territory. They also probably want to avoid being seen as supporting Israel, even if indirectly.

[2] I am very grateful to Prof. Thomas Juneau of the University of Ottawa for the insights he shared on the Houthis, which helped inform this analysis.