This article originally appeared in Policy Options.

By Alexander Dalziel, April 2, 2024

Greenland’s geopolitical value is on the rise and its international vision includes Canada. It is time for Canada to step up in response and not get left behind by its allies.

In February, Greenland released an Arctic strategy, then followed it in March with a full-court press to promote its mining sector at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada convention, one of the world’s largest industry symposiums.

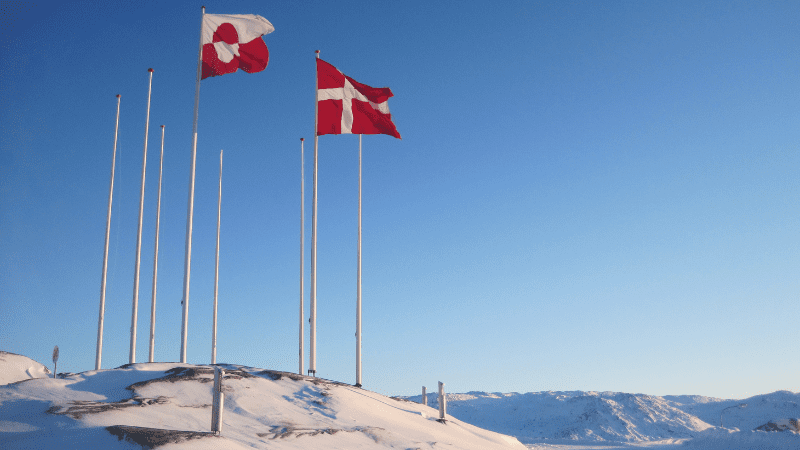

Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. In the Greenlandic language of Kalaallisut, it is called Kalaallit Nunaat. It already exercises most domestic governance responsibilities. Copenhagen has also given it leadership on the Arctic and a presence at NATO.

Greenland wants to achieve full independence in the long term. While the relationship is not tension-free, Greenland and Denmark have a political framework to guide that path. Should that happen, it will be a microstate with a macro territory. Inhabited by about 56,500 people, its land mass is bigger than the entire U.S. Eastern Seaboard.

The United States, the European Union (E.U.) and Iceland are all increasing ties with Greenland at this critical time. Canada should do the same, or even more, especially in terms of furthering diplomatic relations, fostering greater multinational Inuit collaboration, helping with security and increasing bilateral trade.

Greenland’s Arctic strategy has key goals for its relationship with Canada. It wants more human mobility, trade and communication. It wants to engage more across Northern Canada, especially with Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland across Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, northern Quebec and Labrador. Mining and education are two of its priorities.

Sadly, though, the U.S. and the E.U. are showing more initiative than Canada in increasing ties.

In 2023, Greenland signed a strategic partnership with the E.U., centred on linking its mineral deposits to the E.U.’s ambition to increase energy self-sufficiency and diversify suppliers.

The U.S. is approaching Greenland with renewed seriousness of purpose. At the prospectors’ convention, senior officials called it a key partner in building resilient supply chains, and U.S. companies are backing that up with investment dollars.

Both the U.S. and E.U. are looking at this through the lens of their strategic competition with China, which dominates the mining and processing of the minerals and rare-earth elements that are essential to manufacturing digital hardware and energy-transition technology.

Geoeconomics, therefore, may be Greenland’s path to independence. Its mining sector today is small, but its formidable terrain holds an array of critical mineral and rare-earth deposits and it is seeking partners and investors to mine them in socially and environmentally sustainable ways.

Canada’s three interests

Canada has at least three distinct interests in increasing ties.

First is economic security. Canada also wants to be less dependent on Chinese supply chains. As a major source of mining expertise, Canada can participate fully in Greenland’s economic development and has the know-how to overcome the challenges of resource extraction in remote locations.

Second, Greenland is a large piece of the North American security puzzle. Securing Canadian airspace and sea lanes will focus more on Greenland as the Arctic sea ice recedes and more ships ply northern waters. The U.S. has led this relationship since the Second World War, but Canadian fighter jets regularly fly out of the U.S. Pituffik Space Base in northern Greenland.

Third, co-operation with Greenland advances Indigenous reconciliation and therefore strategic economic competitiveness in Canada. The geoeconomic case for reconciliation is strong. Presentations at the prospectors’ conference described a world in which success in the mining sector will hinge on relationships with Indigenous communities as co-owners and co-decision-makers.

Canada and Greenland are home to the majority of the world’s Inuit and together could create a well of knowledge-sharing and sustainable practices to see projects advance for the long term.

What could be next?

Greenland has made its case and calls for more from Canada. How might we respond?

First, the federal government should immediately open a consulate in Nuuk, the capital. The U.S. and Iceland have already done so and the E.U. is about to join them.

Staff it with a Kalaallisut-speaking and Danish-speaking team and include space for the Inuit Nunangat, provinces, territories and other First Nations. Like the U.S., that consulate should have a foreign-aid budget to ensure Canadian presence across Greenlandic society.

Second, build on the work being done by the Inuit to support more transborder social interconnections among Inuit Nunangat and Kalaallit Nunaat.

Third, Canada should advocate for full participation in Greenland’s security. The big goal would be entry into the U.S.-Danish-Greenlandic defence agreement – focusing on a bolstered Canadian contribution of maritime, aerospace and comprehensive security resources.

As well, the Canadian Rangers and the Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary have experience and expertise that would help the Greenlandic government set up its own civilian security structures. Canada might also call together national and subnational actors for a discussion among U.S., Greenland and Iceland on the evolving security needs of the extended region.

Finally, there is trade. Ottawa should immediately lead a bilateral effort to bring down barriers. More strategically, Ottawa might lead a quadrilateral push with the U.S. and Mexico to examine comprehensively removing trade barriers and paving the way, should Greenland so desire, for it to join the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement.

Greenland is a neglected part of North America’s geography, with a rich Indigenous and Nordic heritage. Its geopolitical relevance is rising for Canada. We don’t even need to knock: Greenland has opened the door, and Canada should walk through it.

Alexander Dalziel is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Ottawa. He worked for more than 20 years in Canada’s national security community, including positions at the Privy Council Office, the Department of National Defence and the Canada Border Services Agency.