July 19, 2012 – In today’s Ottawa Citizen, MLI’s Brian Lee Crowley and Ken Coates write an op-ed on First Nations and the future of the natural resource economy. Crowley and Coates say, “This new resource-based wealth could be the key to progress in ending the shameful plight of too many First Nations people in Canada.” The op-ed was republished in the Calgary Herald and Vancouver Sun. It is copied below:

Resources are key to success for First Nations

By Brian Lee Crowley and Ken Coates, Ottawa Citizen, July 19, 2012

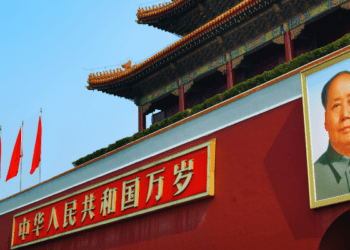

Regardless of short-term ups and downs, Canada’s resource economy is booming as never before. Industrialization and urbanization, chiefly in Asia, will be the unstoppable engine driving the world’s appetite for our resources. This should be an opportunity for all Canadians, but especially for many aboriginal Canadians who inhabit the land surrounding the mining and energy projects underway or planned across the mid and far North.

In fact this new resource-based wealth could be the key to progress in ending the shameful plight of too many First Nations people in Canada. To do so, however, we are going to have to change behaviour and expectations on both sides of the aboriginal/non-aboriginal divide. Happily, this is far from being a distant and improbable prospect. We can already discern the new shape of the relationship.

Indigenous conflict with resource developers is hardly new. Since the arrival of Europeans, mass evictions, pollution and social turmoil related to resource wealth have been facts of indigenous history.

In one of the most profound changes in recent Canadian history, however, aboriginal people are now poised both to shape and capitalize on the wealth-producing possibilities of resource extraction.

We don’t appreciate the positive significance of what has happened because too many of us are still stuck in the politics of confrontation of the 1980s and 1990s. Then indigenous leaders fought for political attention, constitutional guarantees, redress of historical grievances, land claims settlements, self-government and resource rights. That generation of indigenous leaders was hugely successful, and changed the country in the process.

Moreover, the Supreme Court has decreed governments and mining companies have a duty to consult aboriginal people before proceeding with development projects. Like it or not, indigenous peoples will henceforth be major players in Canada’s resource economy.

In other words, Canada has said “yes” to many of the demands of indigenous Canadians.

But the most important — and subtlest — change has taken place inside aboriginal communities. A new generation of leaders preoccupied with economic progress has emerged. First Nations and Inuit communities across the country have set up development corporations, joint venture companies with resource firms, locally and community-owned businesses, and consulting operations. Hundreds of aboriginal students each year attend college and university programs, studying everything from business to engineering, the mining trades and environmental remediation. Thousands of aboriginal people now work in the resource sector, with the numbers swelling yearly.

The new realities have also penetrated the corporate boardrooms of the land. Companies are increasingly moving beyond minimum legal requirements, developing substantial partnerships with First Nations and Inuit communities, realizing that such actions are not feel-good window-dressing but sound business practice. Companies that engage thoughtfully and respectfully with indigenous communities and governments can speed up their projects, secure a trainable local workforce, improve company-community relationships, collaborate on environmental protection and get more local economic impact from resource development. Significantly, the Canadian Council of Chief Executives recently called on governments in Canada to get with the program.

While confrontations and difficulties are still common — just think the Ring of Fire in northern Ontario and the Enbridge Pipeline — there are many more instances of indigenous co-operation with resource companies. Blockades may be news, but the new joint ventures, long-term training programs and successful indigenous businesses are what will reshape our common future. Efforts by Suncor and Syncrude in the oilsands, Cameco in Saskatchewan, the innovative diamond mine collaborations in the Northwest Territories and the path-setting Baffinland project in Nunavut will ultimately alter Canadians’ view of indigenous participation in the resource sector.

The fundamentals of indigenous political and economic life have started to shift. So much remains to be done to alleviate poverty, community dysfunction and suffering, and cultural and language loss, though, that many of us overlook what First Nations and Inuit people have, in partnership with Canada, accomplished in recent decades.

Resource issues played a significant role in the debates leading up to this week’s Assembly of First Nations elections. All of the contenders for national chief made it clear that they expected First Nations people to get better returns from future resource development. The election, however, will likely only change the speed, not the trajectory, of indigenous engagement with mining and energy projects. Aboriginal leaders have started to learn to take “yes” for an answer; Canadian governments and businesses are prepared to work with First Nations and Inuit governments and communities as partners in development.

Our new-found resource wealth confronts Canada with a rare conjunction of urgent need and remarkable possibilities. Many (but not all) First Nations and Inuit communities want to participate in the resource economy, provided that the terms are right. Many (but not all) indigenous leaders are forging new and mutually beneficial arrangements with companies to produce jobs for their people and wealth for their communities. Canadian law compels engagement with aboriginal peoples and their governments. Economic self-interest surpasses even these legal obligations.

If First Nations and Inuit leaders stay the course, and continue their collaborations, if resource companies keep their commitments and sustain their engagement, and if governments support this unprecedented pattern of co-operation, the socio-economic calamities that have so long defined Aboriginal communities could start to give way. For years, indigenous leaders have railed against the soul-destroying elements of welfare dependency and abject poverty. The 21st-century resource boom holds the potential to set all Canadians, aboriginal and non-aboriginal alike, on a new more promising path.

Ken Coates is Canada Research Chair in Regional Innovation at the University of Saskatchewan and Brian Lee Crowley is managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, a public policy think-tank in Ottawa.