By Heather Exner-Pirot

January 15, 2024

When German Chancellor Olaf Scholz watched the country’s first ever floating LNG import terminal land in Wilhelmshaven on the northern shores of Germany on a cool December morning in 2022, he must have felt a deep sense of satisfaction. Only nine months and 18 days had passed since his famous Zeitenwende (“a changing of the times”) speech made in the Bundestag, just three days after Russia invaded Ukraine, in which he committed to reducing dependence on Russian gas and building that very terminal (Germany 2022a).

Those who build, invest in, or closely follow major infrastructure developments were rightly struck by how quickly Germany managed to build its first LNG import terminal. Europe, Canada, and the United States are all bogged down in policy labyrinths of permitting, regulatory approval, and public consultations, a situation that is confounding progress in both economic development andthe energy transition. The long timelines and bureaucratic risks imposed on proponents worldwide are discouraging investment in major infrastructure at a time when we could not need it more, to address a variety of climate, economic, and security goals. As such, a Western example of major infrastructure being built at pace is both welcome and of great interest.

The key to Wilhelmshaven’s success, and other LNG terminals that have followed, was the development and implementation of the German LNG Acceleration Law: federal legislation that simplified and sped up a myriad of administrative and legal procedures, from environmental and energy laws to public procurement rules and general administrative law, all within a context of overlapping state, federal, and European laws (Germany 2022b).

This commentary reviews the key milestones and actions that allowed Germany, a climate conscious and legally complex jurisdiction, to overcome the stasis that has often plagued Western nations in their efforts to build new and much needed infrastructure – in the form of an LNG import terminal – when a political and economic crisis dictated that it must.

It is a hopeful story, and one that shows that Western nations can still build when they want to.

The Gasnotstand

This story begins, of course, with Germany’s Gasnotstand, or “gas emergency,” provoked by Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. While most of Europe depended to some extent on Russian gas delivered cheaply by pipeline, Germany was particularly reliant. Before the war, it received upwards of 55 percent of its natural gas supply from Russia, which supported Germany’s vast industrial and chemical complex (Eberly, Harris, Moll, et al. 2023). It did so despite, and perhaps even because of, Russia’s illiberal behaviour, with many seeing mutual economic interdependence as a strategy to constrain Russian misbehaviour.

Putin’s incursion into Ukraine made this dependence unsustainable. On February 27, 2022, Scholz addressed the Bundestag, Germany’s Parliament. The centerpiece of the speech was the announcement of a €100 billion defense fund, but Scholz also committed Germany to the rapid construction of LNG terminals:

[W]e will change course in order to eliminate our dependence on imports from individual energy suppliers. After all, the events of recent days and weeks have shown us that responsible, forwardlooking energy policy is not just crucial for our economy and our climate. It is also crucial for our security…

We have made the decision to rapidly build two LNG terminals in Brunsbüttel and Wilhelmshaven. I would like to expressly thank Federal Economics Minister Habeck for his efforts to facilitate this! Our current short-term needs can dovetail with what is already needed long-term for the transformation to succeed. An LNG terminal that today receives gas can tomorrow be used to import green hydrogen. (Germany 2022a)

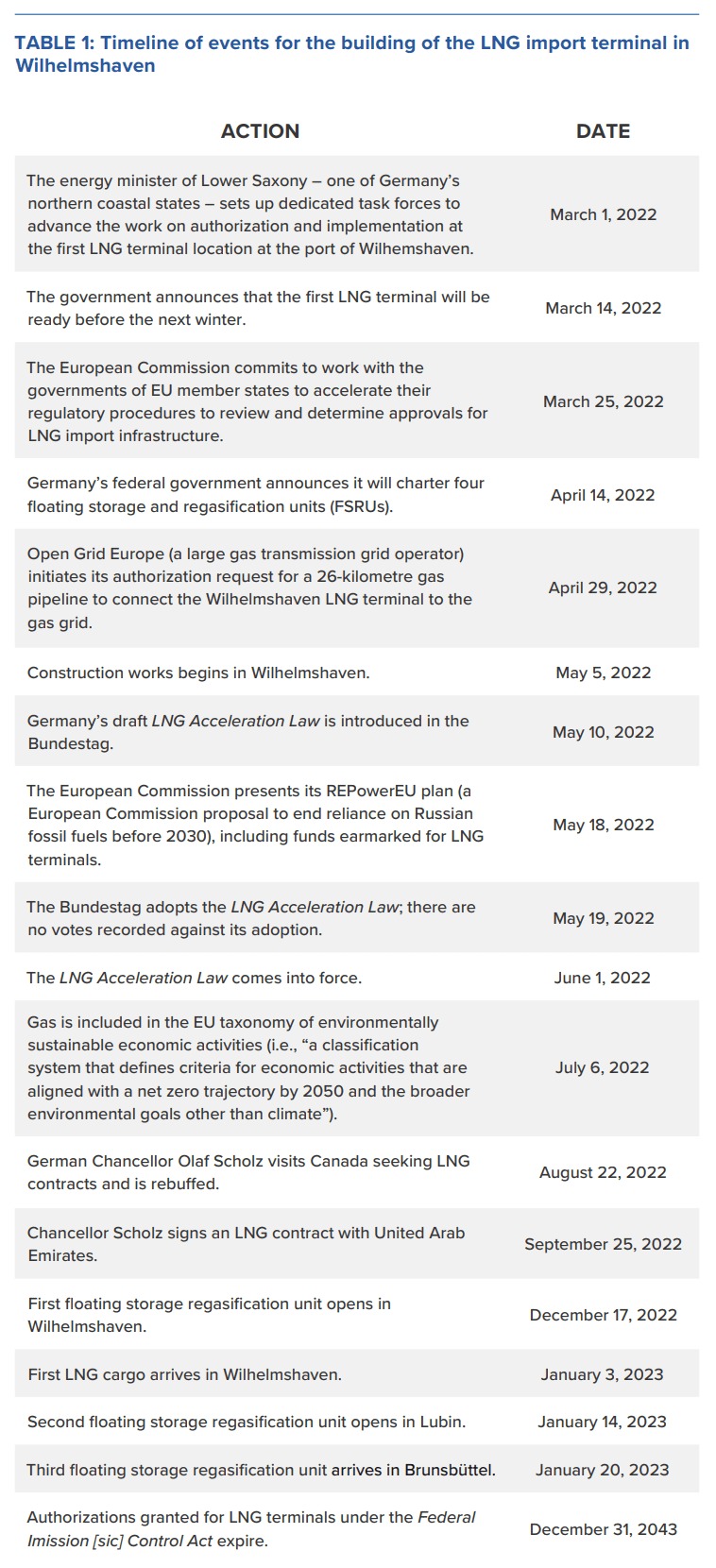

While some observers were skeptical that such a task could be accomplished,

the events of the next two months put all doubts to rest. In short order, a task

force was created, timelines announced, orders placed, and authorizations

requested (see Table 1).

The German LNG Acceleration Law

Central to Germany’s achievement was the rapid passing and broad support for its LNG Acceleration Law. The law was required to simplify and speed up a variety of administrative and legal procedures, from environmental, water, and energy laws to public procurement rules and general administrative law, for the purpose of building LNG infrastructure.

In April 2022, the federal Ministry of Economy and Climate Protection, consulting closely with the Ministries of Environment and Justice, prepared a draft of what would become the LNG Acceleration Law and consulted with other ministries about it. On May 10, 2022, the three coalition parliamentary groups (Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Green Party, and the Free Democratic Party (FDP)) introduced it in the Bundestag.

The explanatory memorandum, underlining the exceptional nature of the legislation, included the following:

With Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, which began on February 24, 2022, the energy and security policy assessment of dependence on Russian gas supplies has changed unexpectedly at short notice and fundamentally.

As a result, an interruption of Russian natural gas supplies to Germany (currently 40 percent of the national gas supply, with a total consumption of around 1,000 TWh or 96 billion m3 per year), which have been central to the national energy supply to date, can no longer be ruled out.

This has created an unpredictable, exceptional, and extremely volatile situation on the gas market. Against this background, it is extremely urgent and imperative to build up immediately and as fast as possible a more independent national gas supply.

Due to the low substitutability of gas by other energy sources, gas must necessarily be procured from other sources in order to secure the supply. One of Germany’s few options for procuring additional gas volumes on the world market at short notice is to purchase liquefied natural gas (LNG). In order to be able to land, regasify and transport the LNG in Germany, the immediate expansion of the LNG import infrastructure is indispensable.

The goal of the law is to move through all approval and permit procedures, as well as the awarding of public contracts and concessions, much more quickly than is possible under current law, leading to speedy approvals and integration of LNG into the German market. In order to effectively ensure the fastest possible implementation, the corresponding legal protection must also be accelerated in each case in parallel.

The law also stipulates that the permits for the LNG facilities are to be limited until December 31, 2043 at the latest, in line with Germany’s climate targets. Continued operation of these facilities beyond that date can only be approved for climate-neutral hydrogen and its derivatives. This ensures that the goal of climate neutrality can continue to be achieved by 2045 at the latest, that there are no misguided investments or possible compensation claims, and that lock-in effects are avoided.

The Federal Climate Protection Act sets the legal target of reducing emissions by at least 88 percent by 2040. Greenhouse gas neutrality is to be achieved by 2045. Due to unavoidable emissions in the industrial and agricultural sectors, it is necessary not to allow any emissions-triggering energy conversion for electricity or heat production on a significant scale until 2040. Therefore, a time limit until 2043 is envisaged. Natural gas will have been almost completely replaced as an energy source by that time. (German Bundestag 2022a; author’s translation)

Following its formal introduction, the legislative draft spent just over a week before a total of nine parliamentary committees. The voting patterns at each committee were largely similar, with the coalition parties approving, and the far-left and far-right parties abstaining. The main opposition conservatives (the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Christian Social Union (CSU)) sometimes voted against, sometimes for, or abstained.

There was one major change between the original draft and the introduced legislation that went forward to the Bundestag: the removal of the environmental impact assessment exemption from on-shore facilities. As the report and recommendation from the Committee on Climate Protection and Energy stated on May 18, 2022:

For floating units (Floating Storage and Regasification Unit or FSRUs, i.e., tank storage vessels or stationary floating LNG terminals with regasification plants), the environmental impact assessment is waived because the aim is to land the gas as quickly as possible. The onshore facilities, including port facilities, but also the hinterland connection, would continue to be subject to an environmental impact assessment in order to strengthen the acceptance of such facilities among local residents. (German Bundestag 2022b; author’s translation)

On May 19, 2022, after a short debate, the LNG Acceleration Law was adopted by acclamation. The coalition parties and the conservatives (CDU/CSU) voted for the law (German Bundestag 2022c; author’s translation). The others abstained. No one voted against the law.

As MP Oliver Grundmann of the opposition CDU asserted in debate,

There is still room for improvement, but there are many sensible acceleration points in it. And we are certainly not making energy security in our country a plaything for party political profiling. That is why we are voting for the bill today. (German Bundestag 2022c; author’s translation)

On May 20, 2022, the LNG Acceleration Law passed the Federal Council (the second legislative chamber representing the 16 states), and on June 1, 2022, it entered into force.

European context

While the implementation of the LNG Acceleration Law was within the jurisdictional competence of the German state, the exemption from an environmental impact assessment had to be compatible with relevant EU legislation. That turned out not to be a problem, as parallel developments within the EU were complementing Germany’s efforts.

It was already the case that on March 25, 2022, in a Joint Statement between the United States and European Commission on Energy Security, the Commission had committed to “work with the governments of EU Member States to accelerate their regulatory procedures to review and determine approvals for LNG import infrastructure, to include onshore facilities and related pipelines to support imports using floating storage regasification unit vessels, and fixed LNG import terminals” (European Commission 2022a).

The United States also committed in that statement to “strive to ensure, including working with international partners, additional liquified natural gas (LNG) volumes for the EU market of at least 15 bcm (billion cubic meters) in 2022 with expected increases going forward” (European Commission 2022a).

Subsequently, and just one day before the debate on the LNG Acceleration Law in the Bundestag, the EU Commission presented its REPowerEU plan, a proposal to end reliance on Russian fossil fuels before 2030 that aimed to accelerate the expansion of renewable energies, create energy savings, and diversify the energy supply. The plan also earmarked funds for LNG terminals. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said on May 18, 2022:

We are, for example, proposing to speed up the permitting procedures for renewables. As you might know, today, it can last six to nine years to have the permitting process ready, for a wind park, for example. We now want to define go-to areas and make sure that, there, the permitting process is down to one year. The same goes for the permitting process for associated infrastructure, like grids…

[T]he third part is to look at diversifying away to other suppliers. And here, we know that when Europe acts together, it has more clout. And therefore, the 27 leaders agreed to set up a platform for the joint purchase, as you know, for gas, LNG and hydrogen…We are mobilising close to EUR 300 billion. Approximately EUR 72 billion will be in grants and approximately EUR 225 billion in loans. This will include some financing – round about EUR 10 billion – in missing links for gas and LNG so that no Member State is left in the cold. And up to EUR 2 billion for oil infrastructure in view of stopping the shipment of Russian oil. All the rest of the financing, that is 95% of the overall financing, will go into speeding up and scaling up the clean energy transition. (European Commission 2022b).

The European Commission later proposed, and the European Parliament did not object following a vote on July 6, 2022 (European Parliament 2022), to include specific nuclear and gas energy activities in Europe’s list of environmentally sustainable economic activities covered by the so-called EU taxonomy (an EU-wide classification system that “defines criteria for economic activities that are aligned with a net zero trajectory by 2050 and with broader environmental goals”), saying:

As the Commission believes there is a role for private investment in gas and nuclear activities in the green transition, it has proposed the classification of certain fossil gas and nuclear energy activities as transitional activities contributing to climate change mitigation. (European Commission 2022c)

This decision was significant because the taxonomy advances a common definition for financial and non-financial companies of economic activities that can be considered environmentally sustainable. Activities included in the taxonomy have much better access to capital.

No business case in Canada?

While German governments and industry were making political and logistical miracles happen to advance the construction of the LNG terminals, Chancellor Scholz was visiting prospective suppliers to secure contracts for those terminals. He visited Canada in August 2022 seeking a friendly source of LNG supply, but was infamously rebuffed by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The two agreed to collaborate on clean hydrogen instead (Natural Resources Canada 2022).

While Trudeau has often been quoted as saying there was “no business case,” for Canada to export LNG to Germany, his words were slightly more nuanced. At the press conference with Scholz on August 22, 2022, Trudeau expressed that:

In the medium-term and long-term, Canada can and will position itself to be a key supplier of energy to the world in a net-zero economy. And that means investments in hydrogen, it means more investments in critical minerals… it means investments in a range of solutions.

Conversion plants are usually placed close to the sources of LNG. And, as we look at the possibility of LNG plants on the east coast, able to ship directly to Germany, we find ourselves a long way from the gas fields in western Canada. (Aiello 2022)

The next day, on August 23, Scholz told host Vassy Kapelos on CBC News Network’s Power & Politics that “We would really like Canada to export more LNG to Europe” (Tizhoosh and Zimonjic 2022). One can reasonably speculate that he would not have made the long trip to Canada if he had known beforehand that an LNG deal would not be on the table.

Just one month later, Scholz toured a number of Gulf states to secure LNG deals, which led to deals with the United Arab Emirates and Qatar (ConocoPhillips 2022). Germany also concluded contracts with American and Oman suppliers in 2023 (Financial Times 2023; Jallal 2023).

Although British Columbia and Alberta are Canada’s primary natural gas producers, Quebec and the East Coast do have natural gas reserves. Six LNG export terminals have been proposed in Quebec, Newfoundland & Labrador, and Nova Scotia respectively (Placentia Bay, Goldboro, Bear Head, Atlantic Coast LNG (AC), Énergie Saguenay, and Stolt), with Europe as their primary market.

Énergie Saguenay, which would have imported cheap natural gas via a new 650km pipeline extension from the existing pipeline transportation system from western Canada to eastern Ontario, got far enough in the regulatory process that it could be rejected by both the Quebec and federal governments. Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault delivered his decision, concluding that the environmental impacts of the LNG terminal were not justified, on February 7, 2022 (Guilbeault 2022). At the same time Russia was amassing personnel and military equipment on its border with Ukraine.

Key elements of the LNG Acceleration Law

Germany’s LNG Acceleration Law is perhaps the best and most impressive recent example of how legislation can be designed in a modern western parliamentary and political context to get important infrastructure built fast. There are ample reasons why it should be studied and emulated, not least among them: (1) our collective energy security is at stake as the West seeks to reduce energy and resource reliance on Russia, China, and other authoritarian regimes; (2) it has an impact on the goals of the energy transition, which require unprecedented building of mines, railroads, ports, grids, processing facilities, nuclear plants, renewables, battery storage, and much more; and (3) there is a need to bolster anemic economic growth in the western world to maintain current standards of living.

Politically, the LNG Acceleration Law was successful due to a combination of economic urgency, political will and collaboration; leadership at the highest level (the Chancellor’s office); and clear mechanisms for moving away from LNG and towards hydrogen to be consistent with climate goals and earn public support.

The highlights of the LNG Acceleration Law are outlined below.

1. A narrow scope, a sunset clause, and a phase-out provision, reflecting the exceptional circumstances in which it was enacted

The LNG Acceleration Law reflected the fact that in many ways it was tied to an exceptional emergency situation, i.e., the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The law:

- included a retroactive effect for LNG construction work that had begun before the law came into force, as long as the building process had not been concluded by that time;

- ensured that the acceleration measures included in the law expired as of June 30, 2025;

- applied to only 12 specifically mentioned projects (eight floating terminals (FSRUs) and four land-based terminals);

- undertook that the authorization for all LNG terminals will expire on December 31, 2043 under the Federal Imission [sic] Control Act; and

- set aside many of the restrictions that apply to FSRUs and certain subsidiary infrastructure elements only if an accelerated authorization of these terminals and elements contributes significantly to preventing or coping with the crisis in the gas supply

2. Acceleration measures

The permissions required to build and operate FSRUs and land-based terminals usually require authorization and potentially compensatory and replacement measures under a number of German laws and regulations, most notably the Federal Imission Control Act, the Federal Nature Protection Act, the Water Economy Act, the Energy Industry Act and the Administrative Procedural Code. In addition, the construction and operation of these facilities is normally subject to public procurement procedures.

The LNG Acceleration Law expedites the authorization of – or even exempts from typical requirements – FSRUs, land-based terminals, and certain subsidiary infrastructure. The law also permits waterways to be used for constructing and operating FSRUs or land-based terminals.

Provisions regulating the authorization of LNG terminals typically require the respective authority to balance the public interest in building those terminals with other considerations (e.g., respect for private property and environmental protection). By establishing that there is an outstanding public interest in building LNG terminals, the law simplified and expedited these decisions.

It also established:

- an assumption that LNG terminals would have no detrimental effect on national or international waters, and thus would not be subject to corresponding regulations;

- a provision that legal remedies brought against a decision to authorize an FSRU or land based terminal would have no suspensive effect, allowing construction to continue while any legal proceeding took place;

- a stipulation that legal proceedings concerning the authorization of FSRUs or land-based terminals would be consolidated in the Federal Administrative Court only, and its decisions in these matters would be final;

- a waiver of the “procurement via lots” requirement (allowing in practice for larger suppliers to win and fully execute contracts);

- a waiver of the requirement that public authorities must invite at least three bidders to quote on building these terminals (provided that only one company is capable of completing the project within the very tight deadline that the emergency situation requires);

- a waiver of information and waiting obligations (in which unsuccessful bidders can seek a review of the award process, and during which time a contract may not be signed with the successful bidder) under certain circumstances;

- a shorter minimum time during which the government will consider tender offers; and

- an expedited legal review of public procurement procedures.

In addition, the law allowed an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) to be waived for FSRUs only. Instead of an EIA, the law outlines alternative measures that include publishing, four days prior to authorizing an FSRU, the draft authorization decision including its justification, the essential application documents including documents describing the essential effects on the environment, and the reasons for exempting the project from an EIA.

Environmental compensatory and/or replacement measures that compensate for the LNG terminal’s impact on the environment still have to be determined as part of its authorization. However, under the law these can be determined up to two years after the terminal is authorized.

3. Public consultation

The law streamlines public consultation by giving less time for the public to object to the project, though it still leaves public consultation as such intact. Authorities were also granted the discretion to not hold public hearings for the FSRUs. Despite that, some local authorities still held public hearings to gain social license for the projects.

What Canada can learn

The triumph of Germany’s LNG Acceleration Law puts into sharp contrast the glacial pace at which Canada is joining the ranks of LNG exporters. Long delays and cost overruns in major projects such as Site C, TMX, and Keeyask; the average of 17.9 years to bring mines online from discovery to production (Manolo, 2023); and our ranking of 34 out of 35 OECD countries in 2020 in permitting approval times (Farah, 2022) further serve to illustrate Canada’s lack of competitiveness in this regard.

But it also calls to mind a recent success within our own borders.

Catastrophic flooding in November 2021 in British Columbia resulted in stretches of 10 key highways being closed, including every major route connecting Vancouver and the Lower Mainland to the rest of the province and, by extension, the rest of Canada. Gas rationing and other supply shortages ensued, and Canada was cut off from vital west coast ports. This occurred as British Columbia was still recovering from the extreme heat waves and wildfires of the summer of 2021, and as fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic put immense pressure on supply chains.

BC’s mountainous landscape does not lend itself well to linear infrastructure and there is not much redundancy. The closure of all major highways meant significant economic and public consequences. Original estimates were that the damage would take months or even years to fix.

However, the Trans-Canada Highway (Highway #1) in the Lower Mainland was reopened three weeks after the flooding, and the Coquihalla Highway (Highway #5) was reopened to commercial traffic after 35 days, although additional work continued well beyond that (Potenteau 2021).

As Global News explained, “more than 300 sites needed work, and more than 600 people and 400 pieces of heavy equipment were brought in as a response,” including hundreds of engineers, environmental and archeological monitors, project managers, and construction personnel who worked around the clock (Potenteau 2021).

The response to the damage caused by the floods was a testament to Canada’s engineering and labour prowess and showed that, in a crunch, and with political will and public support, Canada can also build well and fast.

Now we must collectively confront the question of why building essential infrastructure in this country typically generates no equivalent sense of ambition or collaboration, and figure out what we need to do to remove the bottlenecks our policies and laws have created. Germany’s LNG Acceleration Law offers the promise that at least it is possible.

About the author

Heather Exner-Pirot is a senior fellow and Director of the Natural Resources, Energy and Environment program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a Special Adviser to the Business Council of Canada. She is a Global Fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington DC, the Research Advisor for the Indigenous Resource Network and the Managing Editor of the Arctic Yearbook. Exner-Pirot is also a Coordinator at the North American and Arctic Defense and Security Network and sits on the Boards of the Saskatchewan Indigenous Economic Development Network and Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation. Dr. Exner-Pirot obtained a PhD in Political Science from the University of Calgary in 2011.

References

Aiello, Rachel. 2022. “Touting Clean Energy, PM Trudeau Questions ‘Business Case’ for Exporting Liquefied Natural Gas to Europe.” CTV News (August 22). Available at https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/touting-clean-energy-pmtrudeau-questions-business-case-for-exporting-liquefied-natural-gas-to-europe-1.6037556.

ConocoPhillips. 2022. “ConocoPhillips and QatarEnergy Agree to Provide Reliable LNG Supply to Germany.” ConocoPhillips (November 29). Available at https://www.conocophillips.com/news-media/story/conocophillips-andqatarenergy-agree-to-provide-reliable-lng-supply-to-germany/.

Eberly, Janice C., Benjamin H. Harris, Benjamin Moll, Jón Steinsson, and Georg Zachmann. 2023. “How Did Germany Fare Without Russian Gas?” Commentary. Brookings Institution (October 26). Available at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-did-germany-fare-without-russian-gas/.

European Commission. 2022a. “Joint Statement between the European Commission and the United States on European Energy Security.” Press Statement. European Commission (March 25). Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_22_2041.

European Commission. 2022b. “Press Statement by President von der Leyen on the Commission’s Proposals Regarding REPowerEU, Defence Investment

Gaps and the Relief and Reconstruction of Ukraine.” Press Statement. European Commission (May 18).

Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_22_3164.

European Commission. 2022c. EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities. European Commission.

Available at https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en.

European Parliament 2022. “Taxonomy: MEPs Do Not Object to Inclusion of Gas and Nuclear Activities.” Press Release. European Parliament (July 6).

Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220701IPR34365/taxonomy-meps-do-not-object-to-inclusion-of-gas-and-nuclear-activities.

Farah, Carl (2022). “Supercharging Canada’s Construction Permitting Woes.”

Norton, Rose & Fulbright (November 8). Available at https://www.regulationtomorrow.com/ca/supercharging-canadas-construction-permitting-woes/#_ftn2

Financial Times. 2023. “Germany Locks in More US Natural Gas as it Shuns Russian Supply.” Financial Times (June 22).

Available at https://www.ft.com/content/ecdadbf1-1939-4952-b2cc-c84fb1cbe6d6 [paywall].

German Bundestag (2009). Federal Immission Control Act.

Available at https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Download_PDF/Luft/bimschg_en_bf.pdf

German Bundestag. 2022a. Gesetzentwurf der Fraktionen SPD, BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN und FDP. Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Beschleunigung des Einsatzes verflüssigten Erdgases (LNG-Beschleunigungsgesetz – LNGG). Drucksache 20/1742 German Bundestag (May 10). Available at https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/017/2001742.pdf.

German Bundestag. 2022b. Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Ausschusses für Klimaschutz und Energie (25. Ausschuss) zu dem Gesetzentwurf der

Fraktionen SPD, BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN und FDP – Drucksache20/1742 – Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Beschleunigung des Einsatzes verflüssigten Erdgases (LNG-Beschleunigungsgesetz – LNGG). Drucksache 20/1889.

German Bundestag (May 18). Available at https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/018/2001889.pdf.

German Bundestag. 2022c. 37. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag. Stenografischer Bericht. German Bundestag (May 19).

Available at https://dserver.bundestag.de/btp/20/20037.pdf.

Germany. 2022a. “Policy Statement by Olaf Scholz, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and Member of the German Bundestag, 27 February 2022 in Berlin.” Federal Government of Germany (February 27).

Available at https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/policy-statement-by-olafscholz-chancellor-of-the-federal-republic-of-germany-and-member-of-the-german-bundestag-27-february-2022-in-berlin-2008378.

Germany. 2022b. “LNG Acceleration Act: Securing National Energy Supplies.” Federal Government of Germany (June 1).

Available at https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/schwerpunkte/klimaschutz/secure-gas-supply-2038906.

Guilbeault, Steven. 2022. Decision Statement Issued under Section 54 of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012. Government of Canada, Impact

Assessment Agency (February 7).

Available at https://iaac-aeic.gc.ca/050/documents/p80115/142756E.pdf.

Jallal, Craig. 2023. “Germany Signs Milestone LNG Deal with Oman LNG.” Riviera Maritime Media (August 16).

Available at https://www.rivieramm.com/news-content-hub/news-content-hub/germany-signs-milestone-lng-deal-with-oman-lng-77390.

Manolo, Paul (2023). “Discovery to production averages 15.7 years for 127 mines”. S&P Global (June 6).

Available at https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/research/discovery-to-production-averages-15-7-years-for-127-mines

Natural Resources Canada. 2022. “Canada and Germany Sign Agreement to Enhance German Energy Security with Clean Canadian Hydrogen.” News Release. Government of Canada (August 23).

Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/natural-resources-canada/news/2022/08/canada-and-germany-signagreement-to-enhance-german-energy-security-with-clean-canadian-hydrogen.html.

Potenteau, Doyle. 2021. “B.C.’s Top News Stories of 2022: Rebuilding Damaged Highways.” Global News (December 31).

Available at https://globalnews.ca/news/9379632/b-c-2022-rebuilding-damaged-highways/.

Tizhoosh, Nahayat, and Peter Zimonjic. 2022. “Scholz Says Germany Wants More Natural Gas from Canada but Lacks Infrastructure, Business Backing.” CBC News (August 22). Available at https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/scholz-vassy-kapelos-lng-russia-gas-1.6559814.