This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Richard Shimooka, August 25, 2023

My last column discussed the salience (or perceived lack thereof) of defence policy with Canada’s electorate. In the popular conception there is a divide between domestic issues, such as health care, affordability, crime, and so on, that are of primary importance, and foreign affairs, defence, and security issues, which can be focused on once the former are taken care of.

But in reality, the divide is not so neat. How we handle our foreign affairs and defence and security concerns cannot be separated out from the more immediate day-to-day issues. This is because there are other stakeholders with influence on these issues: our allies. And in particular, our biggest ally and trading partner, the United States.

On the surface, this seems like an odd statement since our international partners have no direct voting power, and, as established in the last column, defence issues have a minimal direct impact on voting behaviour.

Furthermore, as Christopher Sands from the Wilson Institute notes, it is economic concerns that dominate Canada’s bilateral relationship with the United States, with some foreign policy concerns lagging behind those. Nevertheless, they and other allies possess a significant ability to sway public opinion and affect Canada’s economic and political situation, and here too defence spending can play an important role that Ottawa ignores at its extreme peril.

A good approach to understanding this dynamic occurred several weeks ago when, during the confirmation hearing of the incoming NORAD/NORTHCOM commander, Republican Senator Dan Sullivan of Alaska raised the issue of Canada’s lack of military spending as an issue that needed to be raised with Ottawa.

Sullivan has made similar comments in the past and this has become a long-standing issue for him. And he is not an isolated case. This view has become widespread among the U.S. national security apparatus. Normally such sentiments are shared in private discussions, while diplomatic protocol pushes individuals to make effusive public statements about Canada’s position as a good ally. However, there are significant signs that this view is gaining currency within the United States. The Washington Post’s expose about Prime Minister Trudeau’s refusal to meet the NATO two percent threshold, the Wall Street Journal editorial page opinion excoriating Canada as a free-rider, and an Economist article expressing the same view are all tangible signs of this growing distrust towards Ottawa within the foreign policy community.

This is a serious challenge because of the nature of the U.S. bi-cameral system of government and the deep bilateral economic and political relationship between the two states. Members of Congress do not compartmentalize, and horse-trading across different policy areas is the norm. In 2016, Utah Senator Mike Lee held up a reauthorization to assist Afghan interpreters—a fairly widely supported bipartisan effort—as a bargaining chip to get other priorities passed.

Because of the depth of the Canada-U.S. relationship, any member of Congress can have a strong ability to affect Canada. In addition to his defence-related committees, Senator Sullivan sits on the Commerce, Environment and Transport committees, all of which have enormous influence on the Canada-U.S. relationship. Consider something like Enbridge Line 5, which transports critical petroleum products from Western Canada and the United States to Eastern Canada. Senator Sullivan sits on the critical committees related to the issue and has been a staunch supporter of pipeline construction in other areas, like Keystone XL. However given his apparent displeasure with Canada’s spending, he may not be so willing to spend his political capital for support.

The executive branch around the presidency, tends to compartmentalize these issues somewhat better—a feature of a large developed bureaucratic state that tends to weigh diplomatic consequences better. Still, they can and have also leveraged national security concerns to advance other priorities.

One of the clearest examples was President Trump’s efforts to slap aluminium tariffs on Canadian imports by labelling Canada a national security threat under Section 232 of the Trade Protection Act. Now to be clear, the administration’s invocation was a patently ridiculous attempt to obtain concession out of Canada.

In response, Prime Minister Trudeau and Canadian diplomats consistently stressed Canada’s military contribution both in the past and present and specifically enlisted members of Congress to assist their lobbying efforts. Ottawa’s approach was necessary given Section 232’s national security justification which required a response that highlighted Canada’s military contributions. But one has to wonder how much more difficult such an effort would be if Canada’s military contributions were widely viewed as insufficient.

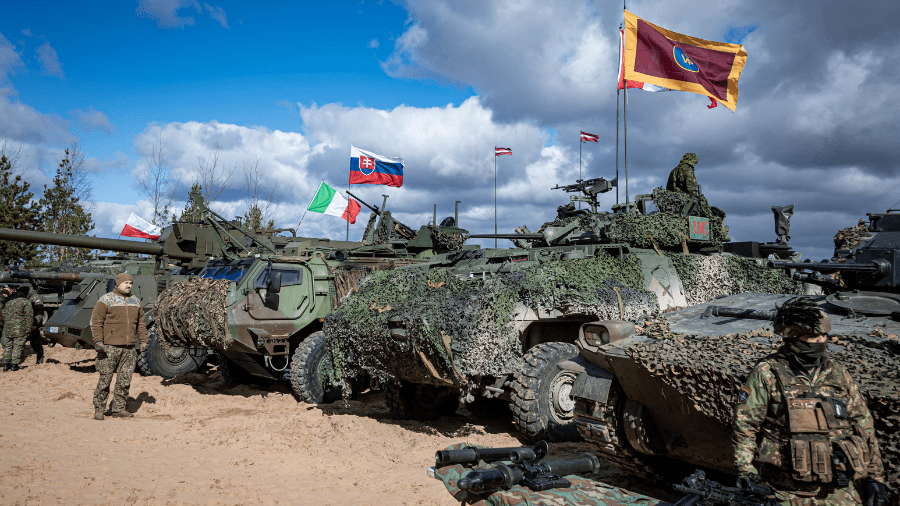

It should be noted that the United States (and other NATO States) calling out allies is by no means a new situation. It has occurred for as long as the Atlantic alliance has existed. Ottawa’s strategy to such criticism in the past few decades has been fairly consistent and similar to how it assuages domestic audiences of its commitment to international security: it uses new foreign commitments to blunt direct criticism. Canada’s deployment to Afghanistan in 2004 in order to avoid joining Operation Iraqi Freedom, the 2016 contribution to the Enhanced Forward Presence in Latvia after NATO Pressure, and the 2017 deployment in Mali all roughly fit the same mould.

These deployments have increasingly stretched the capacity of the CAF, a situation exacerbated by the government’s lack of capital investment in key capabilities. This is particularly acute in the recent announcement of Canada increasing its presence in Latvia to a half-brigade of around 2,000 soldiers. The announcement was made in the days before the Vilnius NATO Summit, where Canada would again be pushed on its failure to meet NATO’s two percent guideline.

For a Canadian public that does not fully grasp the nuances of defence capability, it may seem that the announcement shows that Canada is doing its part. That was the message the prime minister was trying to get across. However, allied governments can easily see through the tactic.

The reality of the Latvia mission expansion is that the deployed forces will not possess a number of key capabilities: a modern multi-layered air defence system that can deal with the burgeoning aerial threat environment or a modern, survivable artillery system that is a critical part of operations in Ukraine. Without such systems, Canadian forces are more of a liability to allied forces than a benefit, as they have to stretch their own capabilities to make up for this government’s deficiencies. Now in some respects, NATO has been as much a political alliance as a military one, and symbolic gestures can overshadow their actual military capability for allies. Yet this is a fairly serious deficiency that calls into question the actual military utility of the commitment. Moreover, in the case of NORAD, the emphasis on actual military performance is much more acute, as Sullivan’s testimony makes evident.

It is unlikely that security concerns will become a major determinant of Canada-U.S. relations; economic and other concerns are certain to remain a larger concern. However, its importance cannot be discounted given the complexity of the U.S. system and defence’s importance in U.S. political circles.

But if the horse-trading model of U.S. government operations is accurate, then Canada is starting in a deficit right from the start. When bilateral issues emerge, and they will, Ottawa will face more calls to make concessions—and will in fact be forced to make them—due to its weak bargaining position. Canada must stop taking the relationship for granted, believing that the historic relationship will survive under the current status quo based simply on shared values and proximity. While these are important, they cannot paper over the serious challenges in the relationship.

Instead, Ottawa needs to take a much more transactional view, especially with Congress, to best represent the country’s interests. Considering the massive scale of Canada’s economic relationship with the U.S., failing to do so will turn out to be a case of being penny-wise and pound-foolish in the long run—with enormous consequences for the country to come.

Richard Shimooka is a Hub contributing writer and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute who writes on defence policy.